Rachel Goldlust, La Trobe University

There is a long history of looking to one’s own garden or small farm when the weight of economic and political chaos becomes too much to bear.

Since the first major depression that hit Australia in 1892-93, there have been calls to get back to the garden as a material response to potential food shortages, and as an emotional salve that lends elements of feeling productive and in control.

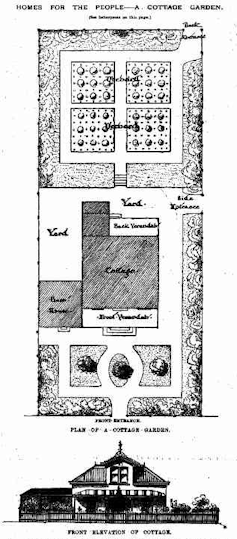

Urban food production in the second half of the 19th century soared. It was common to grow a wide range of vegetables on small plots alongside piggeries, dairies and livestock in the crowded inner and outer suburbs.

Small-scale local production was the most convenient way to make sure local communities could get fresh food. But as a deep recession loomed, there were calls to get people onto the land. A new generation of urban workers started to look for security, autonomy and opportunity in rural or semi-rural self-sufficiency.

Gardening a new landscape

This move towards growing one’s own food was based on dire economic need, but it also came to symbolise a turn away from the modern, providing social and spiritual regeneration.

For early suffragists, self-provision was deeply political. Ina Higgins, Vida Goldstein and Cecilia John started a women-only farm cooperative on the outskirts of Melbourne in 1914. Producing food during the first world war was practical and necessary, while also providing social and economic emancipation.

Allowing women to escape the confines of home and factory, small farming meant they could transgress expectations of labour, marriage and motherhood and re-interpret production as physically beneficial, morally uplifting and socially responsible. It allowed women to take control over their own livelihoods in a way that had been previously unavailable to them.

The hippies of the 1970s started the call once more. With a dedication to homesteading-type activities such as craft, food preservation and practical up-cycling, the children of the post-war generation found comfort in the “old ways”.

These were simple, home-based activities that also fulfilled their desire to set environmental limits and take responsibility for personal resource use. Growing food was not only nostalgic but reflected distrust of advertisements and commercial interests and a general rejection of consumerism, labour and materials beyond the home.

Today there is yet another resurgence in backyard and small-plot food growing, canning, bottling and preserving.

Growing your own food at home may not solve all of your family’s food needs, but the practice of picking, preserving and cooking one’s own food brings a sense of control and calm.

Tips for your own venture into veggie gardening

Observe and interact

Look at the space you have and the resources at hand. Will you grow in pots or in the ground? Think outside the square: can you use your nature strip, a balcony or perhaps even a friend or relative’s garden (while still maintaining social distancing)?

For those growing in the ground, your time is limited as we head into winter, so start small. Remove as much of the existing grass and vegetation from the garden bed as you can. Dig in some quality compost, such as mushroom compost, to improve soil quality.

No-dig gardens sit above the ground, with layers of organic material forming the perfect growing environment for veggies and herbs as they break down. These can be started with very little investment.

You can look to buy (or build) some raised planter boxes that wick up moisture from a reservoir built into the box. Raised garden beds are great for growing small plots of veggies and flowers. They keep pathway weeds from your garden soil, prevent soil compaction, provide good drainage and serve as a barrier to pests such as slugs and snails.

Never reach for a chemical pesticide to solve a bug, weed or disease problem. Build up your soil. Add organic matter, side dress with good compost, use good organic fertilisers. If you pay as much attention to building up the soil in the garden as you do tending the vegetables, your vegetables will practically grow themselves.

Check on your garden daily. The more time you spend there – even if it is just five minutes early in the morning – the more you learn about it.

Look for community

There are mountains of Facebook groups, blogs, websites and community organisations providing resources for basic vegetable gardening. Find one in your area that is suitable for the weather, soils and conditions, and learn from other’s experience.

Local networks will be able to tell you what’s best for planting, how to make a garden if you’re renting, or even share seeds with you!

Even a small balcony box can be rewarding

So what if your spacing is a little off, or you are a week or two late in planting? Or maybe you’ve just started with one tomato plant? A vegetable garden doesn’t require perfection to produce food.

As a way of getting outside, or into nature, or just having a moment to yourself, gardening may be just the reprieve you’re looking for.

Rachel Goldlust, Phd candidate in Environmental History, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.