The news that Japan and the UK have reached a trade agreement in principle was heralded by the government and British press as a landmark for the UK’s post-Brexit trade ambitions. In contrast with British exuberance, the Japanese response has been rather muted, with the agreement viewed as generally comparable to the EU-Japan deal, providing continuity for Japan-UK trade relations.

Any optimism must be tempered by considering the unique circumstances that led to the deal, with the UK leaving the EU and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe stepping down – as well as the likelihood it will have a very limited impact on the British economy. It is no secret that the deal is drawn heavily from the agreement Japan signed with the EU in July 2018, which served as an invaluable starting point for talks with the UK.

And if the UK was eager for a quick conclusion in the face of its negotiating uncertainties over an EU trade deal, Japan’s own need was accelerated by Abe announcing his retirement at the end of August – even though Yoshihide Suga, his successor, looks set to follow similar policies. The two sides were able to weather an apparent breakdown several weeks ago over British cheese to get the agreement over the line.

While the main effect of the deal will be continuity in trade, the negotiators were able to tailor the text to the interests of the two countries. It extends the geographic protections for products like Scotch whisky, and includes provisions governing digital trade that should benefit service providers. The eleventh-hour stilton affair, concerning to what extent the blue cheese would be subjected to import tariffs, was also concluded with minimal concessions on the Japanese side.

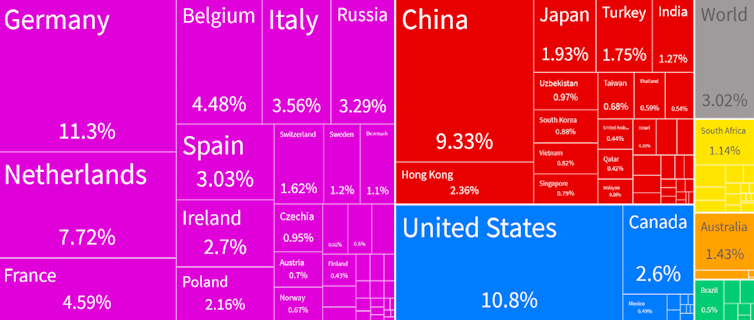

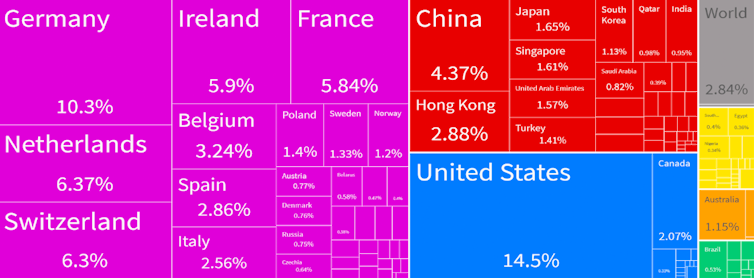

Over the long run, the UK Department for International Trade estimates an increase of what amounts to roughly 50% over the value of current bilateral trade flows. But Japan accounts for less than 2% of British imports and exports, as shown below.

British imports by country, 2020

British exports by country, 2020

Much has been made of the growth prospects for British financial services in Japan, but British providers of these and other services will face challenges in a market with its own established domestic and regional competitors.

For British exporters of manufactured and agricultural products, the distance to Japan also presents a challenge. The costs of trading with Japanese partners are likely to limit entry by new exporters and may constrain expansion by existing players, particularly as pressures from the ongoing pandemic and Brexit-related uncertainty lead British firms to continue to look for ways to reduce expenses.

Next stop CPTPP?

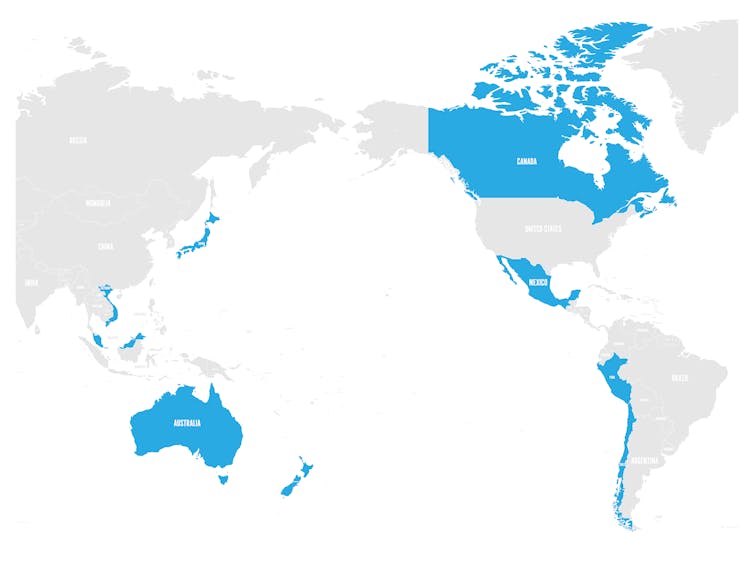

For the British government, the trade agreement with Japan is merely a stepping stone to the more ambitious target of joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). This is the free-trade bloc of 11 nations including Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and Mexico, which is the successor to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement that never came into force because the US withdrew from it in 2016.

Joining the CPTPP would certainly benefit the UK: several of its important non-European trading partners are members, and acceding to the treaty would be simpler than negotiating several new agreements with individual countries.

It may seem a far-fetched ambition for a country that is not located anywhere near the Pacific Ocean (even if the Pitcairn Islands, with a population of less than 50, is a British territory). And yet Australia, New Zealand and Singapore used a jointly authored letter in the Daily Telegraph with UK Trade Secretary Liz Truss to signal a willingness to give Britain a seat at the table, while the Abe government expressed similar sentiments in 2018.

This may merely be cheap talk, as Britain’s involvement would be peripheral to regional political and economic dynamics, and the interests of the remaining seven states are unclear. There is also a risk that if the UK joins the CPTPP that the agreement’s provisions may disincentivise deeper bilateral integration agreements with other members that could be more beneficial in the long term.

The CPTPP members

An additional complication arises from the self-importance, nationalism and colonial nostalgia that have driven Brexit. The UK’s interest in the Pacific has been marked by a neo-colonial drive to project power through economic means. These motivations are unlikely to be appreciated where the UK has all but no physical presence, especially if it attempts to throw its weight around. The recent row over the internal market bill will do little to convince sceptical observers that the UK is a reliable international partner.

Nevertheless, Truss was recently quoted as saying that discussions with countries within the bloc are taking place at the senior official level, while the UK is reportedly looking to submit a formal entry application in the new year.

Meanwhile, the clock is quickly running down on the UK’s ability to negotiate other deals with key trading partners, the most important of which is the EU. Reverting to WTO terms with the rest of the world through the loss of access to agreements signed by the EU will significantly harm the British economy.

And there is an additional concern, both with the Japan-UK deal and with others that may yet be negotiated: trade agreements have uneven consequences within the economies of the countries that sign them. For example, some sectors, such as financial services, are expected to benefit, while for others the effects are less clear. Without attention to these implications, British policymakers would risk exacerbating regional inequalities that have already been made worse by the weak recovery from the 2007-09 financial crisis and now the pandemic.

Michael Plouffe, Lecturer in International Political Economy, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.