One needn’t look further than the humble meat pie to see how our love/hate relationship with Aussie tucker has evolved. In the early 20th century, the dog’s eye was just a cheap staple on our menus and was peddled by roaming pie-carts.

So low was the lowly meat pie that it became a pejorative term for second-rate boxers, racehorses and bookies. The Australian meat pie western took its place alongside the spaghetti western as a low-quality US cowboy flick not actually filmed in the US (the latter were filmed in Italy).

Read more: Oi! We’re not lazy yarners, so let’s kill the cringe and love our Aussie accent(s)

But Australians love an underdog, and things began to look up for the meatie from the second world war. When American soldiers arrived, their “Pocket Guide to Australia” noted that meat pies were

the Australian version of the hot dog.

And since at least the 1970s, we’ve had the high mark of patriotism being as Australian as a meat pie.

Of course, modern Australian (mod Oz) cuisine is much more than meat pies and steak and cake (in the words of author Patrick White). So, we thought we’d play babbler (babbling brook “cook”) and cook up a tale of Aussie tucker and its words — a kind of degustation with gobbets of linguistic and culinary history. .

Classy eating, bush tucker and the wallaby trail

From the time of settlement, Australian eating was a story of haves and have nots.

The first Australian cookbook was released in 1864 under the title An Australian Aristologist. The aristologist was the foodie of the 19th century, but the word never took off, pushed out by others like gourmet — French has always given the dining experience a certain je ne sais quoi.

The Australian Aristologist (prominent Tasmanian, Edward Abbott) extolled the virtues of herb gardens, yeast and 30 or so types of bread, but his privilege led him to largely ignore the core staple of many everyday Australians —damper.

This simple, unleavened bread baked in ashes comprised (along with tea and mutton) the bushman’s dinner. It was the linguistic offspring of the original British damper “anything that took the edge off an appetite” with a verbal twist (to damp down “cover a fire with coal or ashes to keep it burning slowly”).

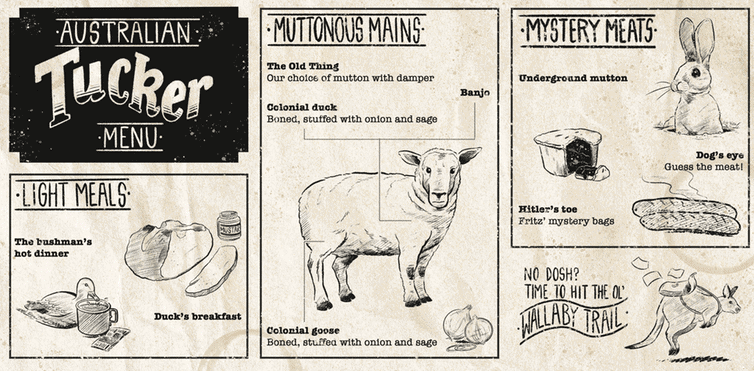

Life could be rough for the bushman and the itinerant worker. Those lucky enough to make tucker (“earn enough to eat”) might tuck in to (“eat”) some banjo (“a shoulder of mutton”), the Old thing (“damper and mutton”) or the bushman’s hot dinner (“damper and mustard”). Those less lucky might be reduced to their billy, a duck’s breakfast (“water”) and the wallaby trail (“the search for food or work”).

The bush diet could be quite muttonous (“sheep-based”), but meat-eating was fraught with gastronomic red herrings (John Ayto’s term). Underground mutton wasn’t mutton, but rather “rabbit”. Colonial goose actually was mutton (“boned leg stuffed with sage & onions”) and so was colonial duck (“boned shoulder with sage and onions”). But Burdekin duck was neither duck nor mutton, but rather “sliced meat fried in batter”. And we reckon seafood fans best steer clear of bush oysters (“testicles”).

Sausage wars and snake’s bum on a biscuit

The Australian food lexicon is often driven by our relationships with one another and the world.

German migration, especially to South Australia, led to the German sausage or the Fritz. However, first world war anti-German sentiment led to attempts to relabel this sausage the Austral. Such renaming efforts were to no avail in South Australia, where Fritz remains Fritz, but were more successful elsewhere.

When the British Royal family changed their surname from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor in 1917, Queenslanders followed suit and the German sausage became the Windsor.

Perhaps our most honest assessment of sausages (but also snags, snaggles, snorks, snorkers, starvers, Hitler’s toe in its many varieties) comes from Australian homes and housewives: mystery bags.

Nancy Keesing’s “Lily on the Dustbin” is a treasure trove of such food slang and metaphor among Australian women and families. Keesing highlights heaps of fun ways of expressing hunger:

I could eat a hollow log full of green ants.

I could eat a horse and chase the rider.

I could eat the bum out of an elephant.

I could eat a baby’s bottom through a can chair.

And there are equally fun and cheeky answers for that perennial question, “what’s for dinner?”:

Snake’s bum on a biscuit.

Wait and see pudding.

Standby pudding.

Open the dish and discover the riddle.

Though humorous, Keesing notes that many of these sayings have sombre origins in the Depression era, when dinner really might have been an unfolding mystery from day to day.

Multiculturalism beyond the “culinary cringe”

South Australian Premier Don Dunstan’s 1970s cookbook begins with the following:

For the most part, before the Second World War, our cuisine reflected the decline into which the average English cook of the nineteenth century had sunk. After the war, the influence of migrant groups […] influenced Australian food habits for the better.

The delightfully named (and delightful) Australian food writer Cherry Ripe announced in the 1990s that we were saying goodbye to the culinary cringe – and ours was among the best food in the world.

Our acceptance of multicultural delights have played no small role in this.

For many years, Chinese and Greek pub cooks were relegated to cooking standard Australian fare (such as steak and eggs). But the dim sim/dim sin has long been a bellwether for the culinary delight to come. In fact, American servicemen in Australia during the second world war were informed in their “Pocket Guide to Australia” that the “dim sin” was the Australian replacement for the hamburger.

Read more: Why would anyone shiver their timbers? Here’s how pirate words arrr preserving old language

But since then, we’ve seen a proliferation of multicultural food items — our cook’s tour has barely scratched the surface. Lots of words are like the cocky on the biscuit tin (“left out”).

We’d love to tell you more about how the chiko roll evolved from observations that chop suey rolls kept falling out of footy fans’ hands. And we’d love to tell you how the lives of the bushmen might have been easier — if they had only taken to the delicacies offered by Australian Indigenous people.

_____________________________________________________

By Howard Manns, Lecturer in Linguistics, Monash University and Kate Burridge, Professor of Linguistics, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.