A Perth man who pleaded guilty to distributing an intimate image of his ex-girlfriend without her consent has been sentenced to a 12-month intensive supervision order, sparing him jail time.

According to media reports, Mitchell Brindley repeatedly created fake Instagram accounts under the name of his ex-girlfriend and posted nude photographs of her on the site.

Brindley is the first to be convicted under new laws that came into effect in Western Australia in April. The new laws carry a maximum possible sentence of three years in jail and fines of up to A$18,000.

What is image-based sexual abuse?

Image-based sexual abuse (or IBSA) is defined as the non-consensual creation, distribution or threats to distribute nude or sexual images (photos or videos) of a person. It also includes altered imagery in which a person’s face or identifying marks appear in a pornographic photo or video, known colloquially as “deep fakes.”

Also known as “non-consensual pornography” or “revenge porn”, IBSA is an invasion of a person’s privacy and a violation of their human rights to dignity, sexual autonomy and freedom of expression.

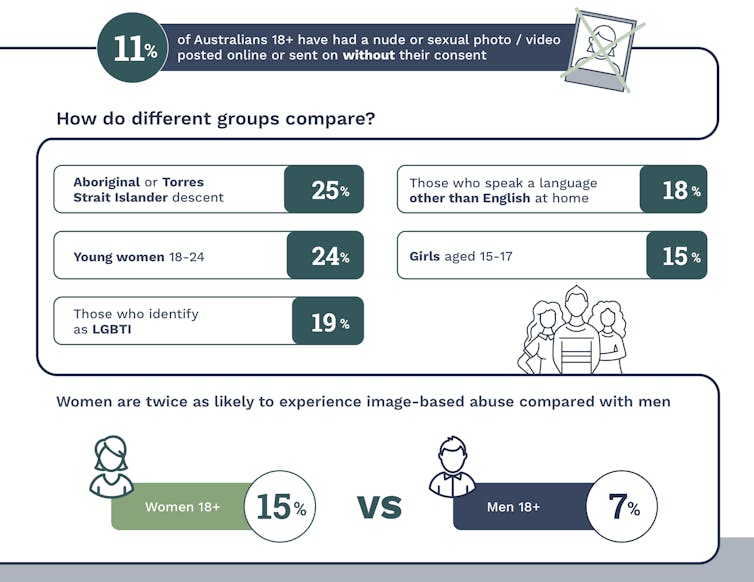

According to research we conducted for the Office of the eSafety Commissioner in 2017, one in ten Australian respondents had experienced a nude or sexual image of themselves being distributed to others or posted online without their consent. Young women aged 18 to 24 were among the most commonly victimised, as were Indigenous Australians and those with a mobility or communicative disability.

In a separate survey we conducted, we found the creation of nude or sexual images was even more prevalent. Of the 4,274 Australians aged 16 to 49 years that we surveyed, 20% said that someone had taken or created a nude or sexual image of them without their consent. Of those surveyed, 9% had experienced threats that a nude or sexual image of them would be shared.

When the creation, distribution and threats to distribute a nude or sexual image were combined, we found that more than one in five (23%) Australians had experienced at least one of these behaviours.

We also asked our survey participants whether they had ever perpetrated image-based sexual abuse. One in 10 reported they had taken, distributed or made threats to distribute a nude or sexual image of another person without that person’s consent. Men (13.7%) were almost twice as likely as women (7.4%) to admit to doing this.

How does IBSA impact victims?

Though the term “revenge porn” implies that the non-consensual sharing of nude or sexual images is based on the spiteful actions of jilted ex-lovers, research suggests the motivations for these behaviours – and the impacts on victims – are far more varied.

For instance, image-based sexual abuse is one way perpetrators of domestic violence attempt to coercively control a current or former intimate partner. Police and service providers have also described to us how images are used to threaten victims of sexual and domestic violence in order to prevent them from seeking help and reporting to police.

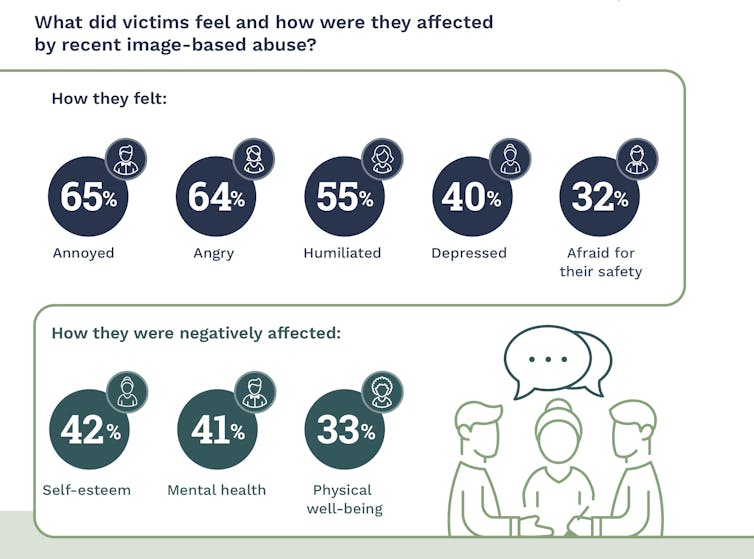

In other cases, nude and sexual images have been used as a form of bullying and harassment, particularly of young people. This can have severe impacts on a victim’s mental well-being, sometimes resulting in self-harm.

Many victims also experience high levels of psychological and emotional distress. In our study, we found approximately one in three people who experienced IBSA felt fearful for their safety – an indicator of potential stalking or intimate partner abuse being linked to the sharing of images online.

Justice responses to IBSA in Australia

Australian laws have come a long way in terms of responding to IBSA. Tasmania is the only state or territory in Australia not to have made it a specific criminal offence.

Several states and territories also allow victims of domestic or family violence to order their partners to destroy any intimate images they may have and prohibit them from distributing such images.

IBSA is also criminalised at the federal level under the Enhancing Online Safety (Non-consensual Sharing of Intimate Images) Act, which was passed last year.

Yet some victims of IBSA don’t want to go through the emotional burden of pursuing criminal charges against a perpetrator. They just want the abuse to stop and the images to be taken off the internet, removed or destroyed. In such cases, victims can report their case to the Office of the eSafety Commissioner, which can issue formal removal notices to social media companies and other online platforms.

Image-based sexual abuse remains a social, health, legal and criminal policy challenge. Sadly, our previous research has found that not all Australians take this form of harm seriously, though there is widespread support for a criminal justice response which reflects the harm image-based sexual abuse can cause.

It is therefore important we continue with a multifaceted approach including education, prevention and training, as well as support services and justice responses, in order to properly address this type of intimate harassment and abuse.

The Office of the eSafety Commissioner operates an online portal with information, advice and assistance for victims of image-based sexual abuse. Visit https://www.esafety.gov.au/image-based-abuse/

The National Sexual Assault, Family and Domestic Violence Counselling Line – 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) – is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week for any Australian who has experienced, or is at risk of, family and domestic violence and/or sexual assault.

_________________________________________________________

By Anastasia Powell, Associate Professor, Criminology and Justice Studies, RMIT University; Asher Flynn, Associate Professor of Criminology, Monash University, and Nicola Henry, Associate Professor & Vice-Chancellor’s Principal Research Fellow, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.