Katrina Moss, The University of Queensland; Gita Mishra, The University of Queensland, and Nicole Reilly, University of Newcastle

One-fifth of Australian women still don’t receive mental health checks both before and after the birth of their baby, our research published today has found. Although access to recommended perinatal mental health screening has more than tripled since 2000, thanks largely to government investment in perinatal mental health, our surveys show there is still some way to go before every mum gets the mental health screening needed.

Mental health issues are one of the most common complications of pregnancy. Up to 20% of women report anxiety or depression either during pregnancy or in the first year after their baby is born.

Maternal anxiety and depression are associated with problems including premature birth and low birth weight. They can also impact child development through effects on parenting practices and impaired bonding.

In 2019, the cost of perinatal depression and anxiety was estimated at A$877 million.

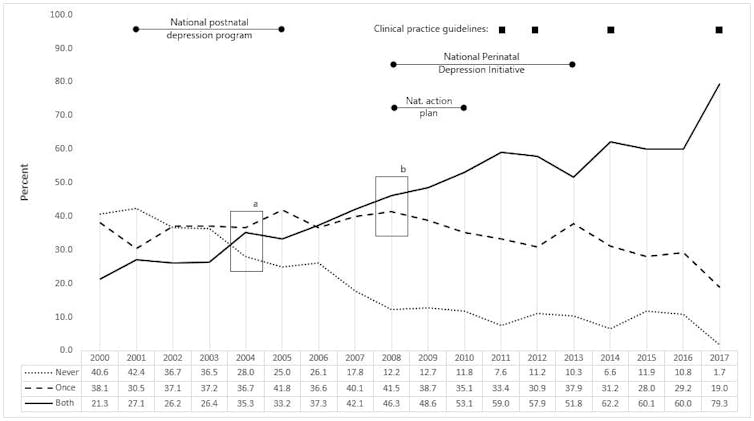

Australia has invested substantially in perinatal mental health screening. From 2001 to 2005, BeyondBlue’s National Postnatal Depression Program screened 52,000 women and reached out to 200,000 families.

This was followed in 2008 by the National Action Plan for Perinatal Mental Health and the National Perinatal Depression Initiative in 2008-13, which supported universal screening and follow-up care, workforce training, and community mental health awareness programs.

National clinical practice guidelines on perinatal mental health care were introduced in 2011 and updated in 2017. In 2019 the federal government committed A$36 million to support the emotional health and well-being of Australian women and families.

Has it worked?

The lack of national government data collection on perinatal mental health screening makes it hard to tell whether this public health investment has paid off.

Our study, published in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, is the first to track perinatal screening over time in a national sample. It included 7,566 mothers and 9384 children from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, which was started in 1996.

We asked mothers whether a health professional had asked them any questions about their emotional well-being, including completing a questionnaire. We mapped screening rates between 2000 and 2017 and compared them to policy initiatives and clinical practice guidelines.

We found the percentage of women being screened both during and after pregnancy has more than tripled since 2000, from 21.3% in 2000 to 79.3% in 2017. The percentage of women reporting they were not screened at all fell from 40.6% in 2000 to 1.7% in 2017.

Our data shows a clear improvement in access to mental health screening. There was a decline in the percentage of women who were only screened once, and an increase in the percentage who were screened both during and after pregnancy. Notably, this widespread transition from single to double screening (the point marked “b” in the graph above) coincided with the introduction of the Perinatal Mental Health National Action Plan and the National Perinatal Depression Initiative, suggesting these policies have delivered real improvements.

However, the timing of this transition differed by state. For example, it happened in 2008 in New South Wales, 2009 in Victoria, and 2010 in Queensland. This might be due to state-based differences in the previous policies and clinical practice, and readiness to implement national initiatives.

What is still to be done?

While our results show there’s been real improvement, it nevertheless remains the case that in 2017, one in five women didn’t receive the recommended mental health screening.

What’s more, women who had reported emotional distress were 23% less likely, and older mothers 35% less likely, to be screened both during and after pregnancy.

Screening is not yet universal – and it needs to be.

There are barriers to screening, including lack of time and potential over-diagnosis. Also, some women who screen positive for mental health problems might not engage in treatment. However, women who are asked about their current and past mental health are up to 16 times more likely to receive a referral for further support. We need to ask mothers about their mental health.

Clinical practice guidelines recommend screening for symptoms of anxiety and depression during pregnancy and during the first year after giving birth. This can be done by trained health professionals. Access to well-integrated and culturally safe care is essential.

Systematic national data collection is required if clinical best practice is to be monitored into the future. Perinatal mental health items have been developed as part of the National Maternity Data Development Project, and should be progressed as a priority.

Women have regular contact with the health system both before and after giving birth. This offers a great chance to identify women who need extra mental health support, and it is too important to be missed.

Katrina Moss, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in maternal and child health, The University of Queensland; Gita Mishra, Professor of Life Course Epidemiology, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland, and Nicole Reilly, Postdoctoral research fellow, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.