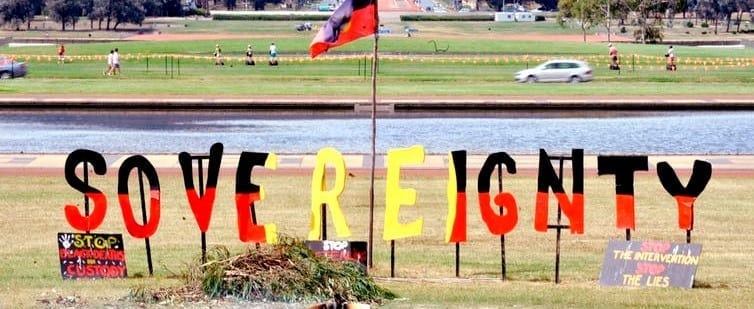

After years of debate, the process for achieving constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians has reached a crossroads. More than a year has gone by since the Uluru Statement from the Heart, when Indigenous peoples rejected symbolic constitutional reform and asked for more practical changes.

Instead of looking at selected components of the Uluru Statement as a solution, there’s another way forward.

We should examine our existing political system and ask how it can be adapted to meet the aspirations of Indigenous peoples while remaining true to the principles that underpin our constitutional democracy.

In other words, we should look to federalism.

What is a federal model?

Federalism aims to bring disparate entities or groups together through a system of shared-rule in a central or national government and self-rule in a state or region.

Federal systems are usually set up on a territorial basis with two tiers of governments, such as the Commonwealth government and state governments in Australia. Each government exercises self-rule with its own legislative and executive powers and has a direct relationship with the people through elections.

However, there are many different versions. Belgium, for instance, has a type of cultural federalism that isn’t defined by just territorial divisions. Membership of a cultural community is defined according to who you are (in Belgium’s case, what language you speak), rather than where you live.

In this type of federal system, cultural communities have power over language, education and other cultural matters, while regional governments take responsibility for land-based issues, such as infrastructure and the environment.

This approach to cultural autonomy is used in other countries, too. In Estonia, for example, a national cultural autonomy law has been enacted that allows any ethnic group of at least 3,000 people to establish a separate legal identity, levy taxes and take responsibility for education, cultural institutions and youth affairs.

In Scandinavia, separate parliaments have also been established for the Indigenous Sámi population. Norway’s Sámi parliament also doubles as an executive branch of government. It was originally a consultative body, but now has power over most measures to promote Sámi culture and oversees compliance with other relevant administrative orders.

The US and Canada, too, have applied this principle in their Indigenous land settlements and treaties. In this system, sometimes known as “treaty federalism”, rights and benefits are based on membership of a group, not just residence.

Importantly, these agreements recognise a mixture of territorial and non-territorial rights. For example, the Nisga’a Treaty signed by the Nisga’a Nation, the British Columbia government and the Canadian government grants the Nisga’a people authority over education, taxation and environmental protection on their defined lands, as well as control over citizenship and social services for members living both on and off Nisga’a lands.

This is precisely what makes federalism for Indigenous Australians viable and worthy of exploration as an option for reform.

What an Indigenous nation would look like

The government-appointed panel on constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians considered allocating seats in parliament to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, but didn’t explore the idea of federalism itself.

Tasmanian Indigenous activist Michael Mansell has called for the establishment of a seventh state comprising Aboriginal lands across Australia. This could be done through legislation, as the constitution permits the parliament to establish new states or territories.

An alternative approach is to follow the non-territorial, cultural model used in Belgium, while at the same time recognising Indigenous rights over traditional lands, such as in the US and Canada.

In this model, an Indigenous “nation” or “nations” would be:

- a constituent unit(s) of Australia, equal in status to the states and the Commonwealth

- represented (have a voice) in the upper house of parliament

- have constitutionally defined executive and legislative powers

- have representation on the Council of Australian Governments

Further, an Indigenous nation would be recognised as a sovereign entity within Australia because of its status as a federal unit with powers of self-government.

These powers may be best negotiated in a treaty and could include the responsibility for making laws, delivering services and ensuring compliance on matters like health and education, native title lands and taxation.

Federalism would therefore go quite some way to delivering on three of the four key elements of the Uluru Statement – providing Indigenous peoples with a voice, driving an agreement-making process (a treaty) and recognising sovereignty.

And if an Indigenous nation agreed to unite with Australia’s states “in one dissoluble Federal Constitution”, this could finally give our constitution legitimacy.

Logical next step

Such an approach may seem impractical, but all the elements already exist or are in the works in Australia.

Native title settlements, for all their shortcomings, recognise distinct groups, define membership in those groups, establish rights over areas of land and allow for government-to-government relationships.

Numerous Indigenous nations, such as the Ngarrindjeri in South Australia and the Gunditjmara in Victoria already have in place the equivalent of legislatures and executive branches that are legally recognised. Federalism is the logical next step.

Further, federalism does not mean that Indigenous peoples would have an extra vote. Like the Máori in New Zealand, Australian Indigenous peoples could choose to vote in an Indigenous electorate or a general electorate.

Self-determination has been the one proven approach to addressing Indigenous disadvantage in other parts of the world. It’s time we realise that federalism is the political structure best suited to delivering this in the Australian context.

___________________________________________

By Michael Breen, McKenzie Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

TOP IMAGE: (By Alan Porritt/AAP)

Explore top-rated compensation lawyers in Brisbane! Offering expert legal help for your claim. Your victory is our priority!

Explore top-rated compensation lawyers in Brisbane! Offering expert legal help for your claim. Your victory is our priority!

"

"