Denise Thwaites, University of Canberra

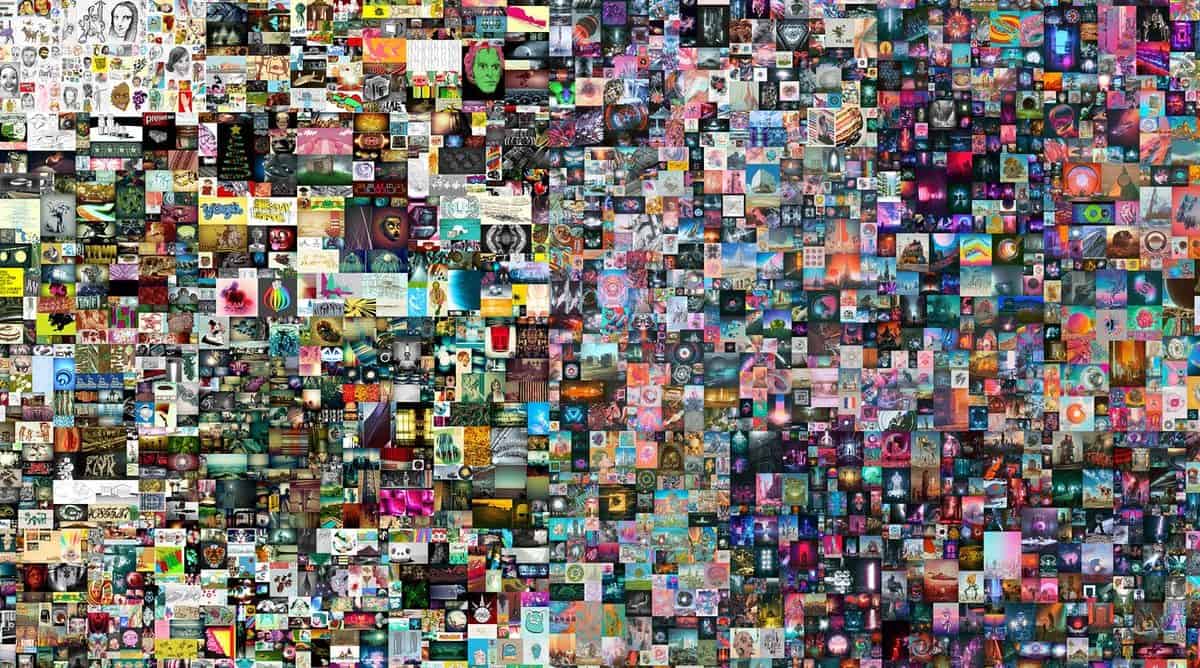

Since May 2007, US-based digital artist Mike Winkelmann (who goes by the name Beeple) has posted a new artwork online every day. He posted the 5,000th one in January, and has now packaged them into an enormous digital collage titled Everydays: The First 5000 Days, which will be auctioned online by Christie’s on February 25.

The work will be sold in purely digital form, as a 21,069 × 21,069-pixel JPEG file and a “non-fungible token” or NFT. NFTs use blockchain technology to give the successful bidder unquestioned ownership of the work.

NFT artworks are becoming a serious business. Last year, Beeple made US$3.5 million on an NFT auction.

But the entry of a global blue-chip auction house like Christie’s into this domain may mark a new stage for blockchain technology, as a widespread tool for both maintenance and transformation of digital art markets.

Not as new as it seems

Christie’s claims the sale of Everydays is the first time a major auction house has offered a purely digital artwork. Christie’s has sold digital works before, including videos (such as Ryan Trecartin’s A Family Finds Entertainment in 2013) and software-based installations (such as teamLab’s Ever Blossoming Life – Gold in 2018).

But these were accompanied by physical trappings, such as certificates of authenticity or fancy hard drives to house the digital files. This time, however, it’s simply the image file and an accompanying NFT.

What are NFTs?

NFTs support claims to an artwork’s value. While the JPEG file of Everydays may be copied, the collector’s blockchain-based record of ownership will allow them to display the work (and to resell it) on a number of online platforms.

Christie’s has teamed up with one such platform, Makersplace, for the deal. Makersplace uses an open standard smart contract for its NFTs, which means the work can be sold in many other places in the the increasingly complex NFT ecosystem.

NFTs are useful in the digital art market because they enable claims to authenticity and scarcity, despite the ease with which digital works can ordinarily be copied. Artists and galleries have tried to create scarcity via limited-edition works and to assure authenticity with certificates, but NFTs seek to automate this process.

NFTs record ownership on a blockchain, which is a decentralised alternative to a central database. Built through cryptography and peer-to-peer networks, blockchains are resistant to tampering and hacking, which makes them useful for storing important records. Vince Tabora from US tech website Hacker Noon has written an accessible explainer of how blockchain is different from older ways of storing and organising data.

Why blockchain?

Ever since blockchains were described in the white paper published by pseudonymous Bitcoin inventor Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008, the idea of a “trustless” way to keep secure public records has evolved into a so-called “confidence machine”, fuelling a considerable amount of hype. Simultaneously, voices have emerged to encourage more nuanced and critical engagement with blockchain’s possibilities and limitations.MoneyLab Reader 2: Overcoming the Hype and There is No Such Thing as Blockchain Art are two key publications exploring these tensions across varied cultural domains.

Carnegie Mellon Researchers have described potential use-cases for the art industry, including securing artwork provenance (see Verisart) or enabling secure forms of fractional ownership (see Maecenas).

And Christie’s is no stranger to new technology. The company has hosted regular Art+Tech Summits since 2018 (the inaugural topic being blockchain).

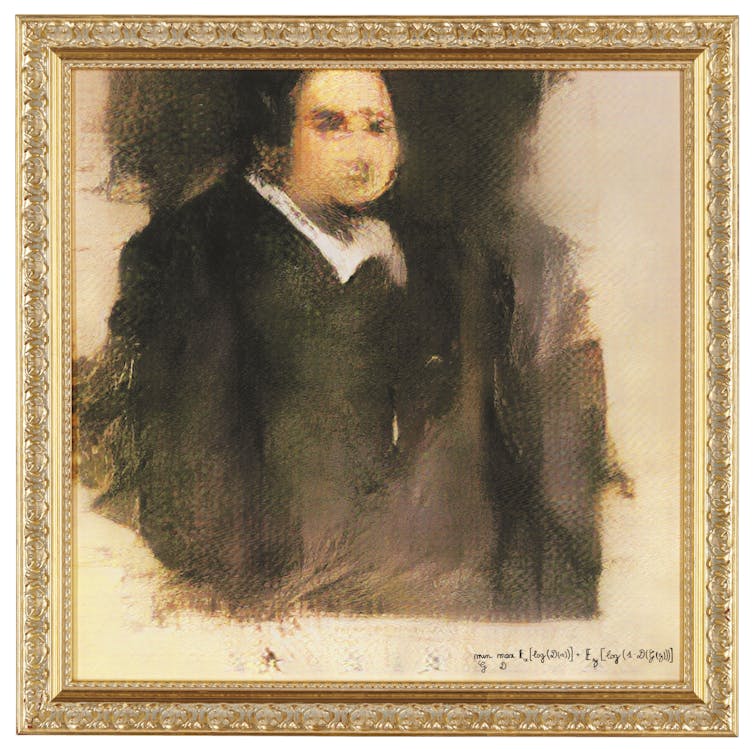

In 2018, Christie’s proudly announced it was “the first auction house to offer a work of art created by an algorithm”, with the sale of the AI-generated painting Portrait of Edmond Belamy for more than 40 times its estimate.

So by selling Everydays as “the first purely digital work” to be offered by a major auction house, Christie’s is reinforcing its self-described “position at the forefront of innovation in the art world”.

Virtual trading cards and CryptoKitties

At the same time, Christie’s upcoming auction is only the tip of the NFT-collecting iceberg. Industry publication Coindesk estimates the total value of the NFT market to be US$250 million. Platforms such as Opensea, Nifty Gateway and SuperRare host a rapidly expanding range of digital collectibles to buy and sell by a growing community of collectors.

Beyond art, digital collectibles include virtual trading cards, artefacts and attire for virtual gaming worlds. They also underpin games such as CryptoKitties, in which NFTs serve to secure the “unique genome” of each kitty in the game. These examples reflect the uptake of NFTs across different digital subcultures, providing collectors with claims to uniqueness that were previously considered impossible in the online realm.

Blockchain for artists

Artists and other creative practitioners may also benefit from blockchain-backed systems.

Researchers at RMIT published a paper on how blockchain infrastructures could help Australia’s creative economy in 2019. They note how blockchains could support artists in trading, creating contracts, getting their work discovered, sharing resources – and making money to support their livelihoods.

Artists themselves are also searching for new ways to use blockchain and other “distributed ledger” technologies. Over the past decade, Furtherfield in London has worked with artists to explore the possibilities and limitations, partnering most recently with Goethe Institute and Serpentine Galleries for The DAOWO Sessions: Artworld Prototypes. Other notable projects include Artists Re: Thinking the Blockchain, which showcases how artists have a stake in this technological shift, and DisCo Coop, Trojan DAO and Black Swan DAO, which examine how new tools for organisation can challenge the value systems of the traditional art market, rather than further solidify them.

Blockchain futures

This reexamination of art in light of blockchain has also been happening in Australia. In 2019, Baden Pailthorpe and I worked with the Bitfwd community to curate a project called Blocumenta, which brought together local artists, designers and hackers to examine how blockchain could affect the arts, culture and heritage in the Asia-Pacific.

More recently, Nancy Mauro-Flude and I co-curated an event called Economythologies – MoneyLab#X, which was co-presented by several universities, galleries and arts organisations. We presented a program of talks, performances and artworks that considered how blockchain’s uprooting of legacy economic systems and narratives opens space to imagine different ways to value, design and organise our creative and cultural practices.

At this stage it’s hard to say exactly what blockchain will mean for art. For now, perhaps we should let Beeple have the last word:

bruh, i just learned wtf an NFT is like two weeks ago, not gonna act like i have a ton of intelligent shit to say here. this crypto space seems super interesting though and i see a ton of potential to do some weird shit nobody has done yet…

Economythologies – MoneyLab#X was co-presented by Centre for Creative and Cultural Research (University of Canberra), Institute for Culture and Society (Western Sydney University), School of Art and Design (Australian National University), Holistic Computing Aesthetics Network and Cultural Value Impact Network (RMIT University), Ainslie+Gorman Art Centre and Bett Gallery , with the support of the Institute of Network Cultures and Despoinas Media Coven.

The Blocumenta Blockathon was co-presented with bitfwd ventures and community, with the generous support of the University of Canberra, ACT Government, the Australian National University, DAOStack and Sigma Prime.

Denise Thwaites, Assistant Professor in Digital Arts and Humanities , University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.