George Wilson, Australian National University and John Read

The US Congress is considering a proposed law to ban the import and sale of kangaroo parts. Backed by a campaign called Kangaroos Are Not Shoes, the bill is aimed at stopping Nike, Adidas and other big brands from using kangaroo leather in their products.

Supporters of the bill decry the “mass slaughter of kangaroos – more than two million a year”.

We have a combined 80 years experience in kangaroo management. In our view, this proposal is one of the most comprehensive own goals in history of improving kangaroo welfare. Our research shows the kangaroo industry leads to better kangaroo welfare, more stable populations and improved conservation outcomes.

Weakening the industry will result in more kangaroo suffering, not less. If the bill succeeds, it would further suppress global demand for kangaroo products, and allow unregulated, uncontrolled and unmonitored killing by amateur hunters to flourish.

The industry state of play

Kangaroos are widely dispersed and abundant on the temperate Australian rangelands where cattle and sheep are raised. Over the past 200 years their numbers have increased steadily due to greater availability of pasture, increased watering points, dingo control and less Indigenous hunting. In the rangelands where aerial surveys are conducted, the kangaroo population is estimated at more than 40 million.

Harvesting of kangaroos in Australia is tightly controlled by state and federal governments, and quotas are set to ensure only a sustainable proportion of kangaroos are commercially harvested.

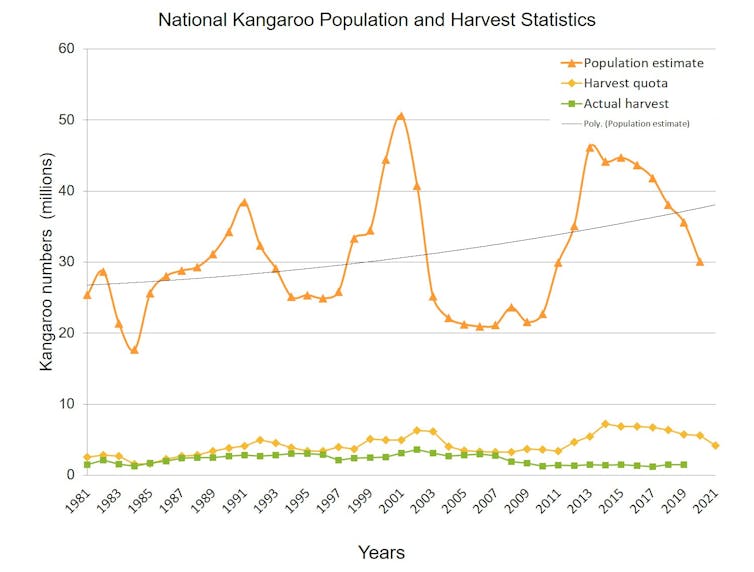

The graph below shows how only a tiny proportion of Australia’s kangaroo populations is harvested commercially each year, and at numbers far less than quotas allow.

In 2018 for example, the kangaroo population in commercial harvest areas in New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia was about 4.25 million. The following year, a sustainable quota of 674,000 was set (15.9% of the population). However, just 88,472 kangaroos, or about 2% of the population, were harvested.

The commercial kangaroo industry employs accredited, licensed shooters who kill kangaroos in the field at night using high-powered spotlights and rifles. A national code of practice requires that kangaroos are shot in the head and die immediately.

Abattoirs reject carcasses not killed with a headshot. Commercial shooters must not target females with obvious young in their pouch or at foot. If a mother is shot, the joeys must also be killed using sanctioned methods.

Kangaroo meat is sold in Australia – to the food service industry, retail outlets and as pet food – and exported to many countries.

Managing kangaroo numbers

Kangaroo numbers decline in droughts and rise in good seasons. They roam from property to property, and in and out of national parks, seeking best pastures in response to local rainfall.

Overabundant kangaroos are a serious issue for threatened plants and animals and revegetation programs. They also compromise landholders’ ability to manage their properties. For example, during drought, kangaroos graze on valuable pasture, making it harder for farmers to keep cattle alive.

Because the commercial industry harvests so few kangaroos, landholders must take steps to prevent the animals from damaging their properties. They erect fences around clusters of properties, often with government support, to exclude kangaroos from pastures and watering points.

They use amateur shooters and even illegal poisons, to reduce kangaroo numbers on their properties. Our research shows the number of permits for non-commercial culling of kangaroos is increasing and in recent years exceeded the commercial harvest.

Overabundance can also affect the welfare of the animals themselves. During the recent drought, for example, millions of kangaroos starved and breeding was suppressed, causing kangaroo numbers to fall markedly.

According to the NSW Department of Primary Industries and the RSPCA, professional marksmen, operating within a commercial industry, are the most humane way to manage kangaroo populations.

When kangaroo kills are brought in for processing, regulators can monitor the industry’s compliance with welfare codes. Such monitoring is nonexistent with amateur culling.

We believe a further decline in the kangaroo industry – the goal of the proposed US legislation – will lead to worse animal welfare outcomes. It will prompt more amateur culling, and risks mass kangaroo starvation in the next drought.

Where to now?

We welcome the Australian government’s opposition to the bill. Regardless of whether the bill succeeds, a broader question remains: what should Australia’s future kangaroo industry look like?

We believe an alternative vision is required – one in which consumer demand for kangaroo products increases. Landholders would then consider kangaroos, including the young, valuable rather than pests – creating a form of custodianship and an incentive to integrate kangaroos with other farm enterprises. This would lead to more effective management and animal welfare outcomes.

Key to encouraging farmers to value kangaroos is increasing public demand for – and therefore the price of – kangaroo products. But in recent years, demand has been falling. For example, in 2016 California banned the import of kangaroo skins. This rendered them worthless and led to a processing plant at Broken Hill discarding them as town waste. Our research found in 2018 a kangaroo was worth as little as A$13 – much less than goats (A$70), sheep (A$100) or cattle (A$800).

Demand for kangaroo products could be increased by promoting:

- the positive health attributes of kangaroo meat

- the leather’s high strength-to-weight ratio

- the ethical advantages of field harvesting.

Kangaroos can benefit landholders in other ways. Their soft feet cause less damage to soils than hard-hooved introduced livestock. And farmers could earn carbon credits through better management of grazing pressures and substituting high-emission meat and leather for kangaroo alternatives.

We urge the federal government to show leadership and work with the states to improve kangaroo management. Doing so would seem a great project for the Future Drought Fund.

A stronger kangaroo industry integrated with the other red meat industries, delivering high-value products, is possible. But the US bill is not the right way forward.

George Wilson, Honorary Professor, Australian National University and John Read, Associate Lecturer, Ecology and Environmental Sciences

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.