Daniel Laufer, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

In Australia, New Zealand and around the world, COVID has turned luxury and semi-luxury hotels into quarantine facilities.

Among the four and five-star hotels reported as having been used for temporary detention are Sydney’s Intercontinental, Marriott, Hyatt Regency, Sheraton Grand, Sofitel Wentworth and Novotel Darling Harbour; Auckland’s Rydges, Crowne Plaza, Grand Millennium, Four Points by Sheraton and Ramada; and Melbourne’s Stamford Plaza, Mercure, Park Royal and Rydges on Swanston.

Each has had a valuable brand name.

Governments prefer four and five-star hotels to small ones because they are large (200 rooms or more) and easier to run as quarantine facilities.

It’s hard to blame the big international hotels for taking part. Without income from international tourists, they’ve needed the money.

But by taking the money and becoming known as places where people are locked up, at times cross-infected, and fed food ranging from “nice” to “atrocious”, they run the risk of destroying brands that took decades to build.

‘Associative interference’

It would happen through a process known as associative interference, where it becomes difficult to focus on old and relevant information about something because new and less-relevant information gets attached to it and gets in the way.

A recent memory of something much less glamorous can contaminate a lifetime of memories associating a brand or an experience with luxury.

This can happen both at the general level (“hotels are no longer a place I am particularly keen to spend time in, even five-star ones”) and at a specific level (“this particular brand that I always associated with quality I now associate with something less savoury”).

In New Zealand the names of hotels designated as COVID-19 facilities are announced in press conferences, published on an official website and reported in the media.

In Australia, it’s more hit and miss. Word spreads about the hotels being used, especially when things go wrong, even though some seem reluctant to confirm their status.

How damaging could it be?

Brands such as Intercontinental, Sheraton, Hyatt, Rydges and Ramada might be tempted to take comfort from the experience of Corona, the brand of beer.

It ended the year with its sales intact, despite initial concerns. But its only association with coronavirus was a name.

Hotels have been linked to COVID and detention in real life.

Some have been likened to prisons.

One way for COVID hotels to lessen the COVID taint would be to flood people’s memories with something else – their original positioning as places of luxury.

A massive advertising and public relations campaign reinforcing the earlier themes of opulence and quality might, in time, overwhelm the association with quarantine and restore the image the brands once had.

If all else fails, change the name

If the new taint still sticks, there’s an alternative. It’s to abandon the name.

It’s a manoeuvre with an impressive history.

After years of trying to live down Britain’s worst nuclear disaster, the Windscale power plant and reprocessing facility changed its name to Sellafield in 1981.

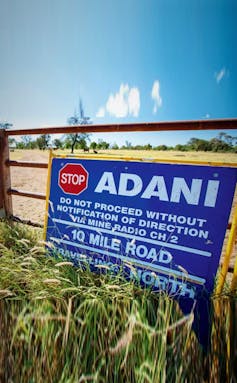

The tobacco giant Philip Morris became Altria Group in 2003, and this year Adani Mining became Bravus Mining in a victory of sorts for opponents of its Queensland coal mine. Australia’s much-criticised Newstart unemployment benefit became JobSeeker.

A new name with no lineage might be better than a familiar one that calls forth memories of 2020.

Daniel Laufer, Associate Professor, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.