Cassandra Steer, Australian National University

As the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) celebrated 100 years with a spectacular and well-attended flyover in Canberra yesterday, many eyes were lifted to the skies. But RAAF’s ambitions go even higher, as its motto “through adversity, to the stars” hints. The Chief of Air Force, Air Marshall Mel Hupfeld, announced the intention to create a new “space command”.

Having a dedicated space command will bring Australia into line with Canada, India, France and Japan, all of which recently created similar organisations within their armed forces. Unlike the US Space Force, which is a separate branch of the military in addition to the army, navy and air force, Australia’s space command will oversee space activities across the Australian Defence Force.

Creating a space command is a smart move — but we must be careful to ensure it doesn’t add fuel to a cycle of military escalation in space that has already begun.

Space technology is vital but vulnerable

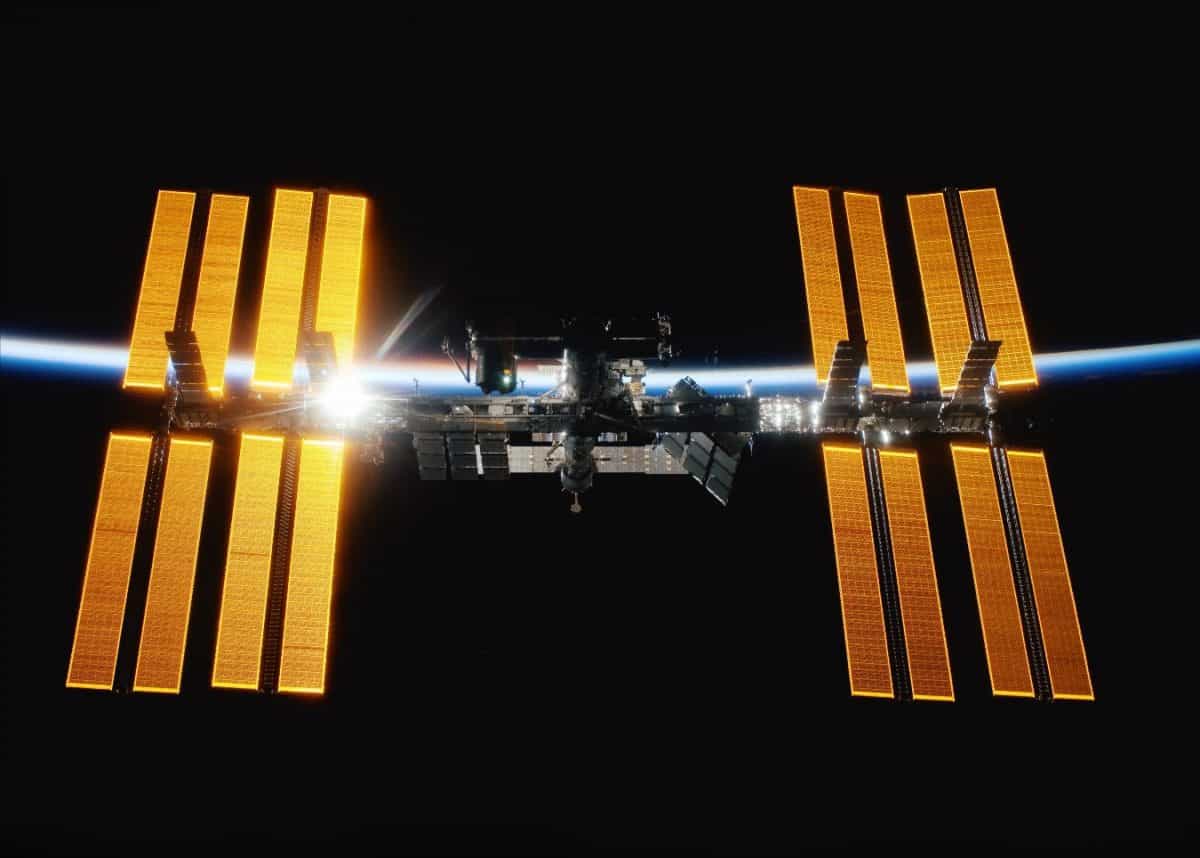

We depend on satellites for communications, navigation, banking and trade, weather and climate tracking, search and rescue, bushfire tracking, and more. A conflict in space would be catastrophic for us all.

There is a risk of “space war” because these technologies are also integral to military operations, both in peacetime and during conflict. If you want to take out your enemy’s eyes and ears, you target their satellites — but not with guns, bombs or lasers.

There are many ways in which so-called “counterspace technologies” might threaten those satellites. This might include cyber attacks, dazzling a satellite with low-powered lasers so that it can’t observe Earth, or jamming a signal so a satellite can’t send data to Earth.

Operating in space

The creation of US Space Force under the Trump administration in 2019 raised many eyebrows, and even led to a parody sitcom on Netflix. But while the comedy series had soldiers waging a war with China on the Moon using wrenches, US Space Force has a serious mandate, including the work that had been done for decades by its predecessor, US Space Command.

Much of that work involves tracking satellites and the estimated 128 million pieces of debris orbiting the Earth, to help avoid collisions that could be fatal to any number of services on which we rely. It also involves protecting US and allied space systems from counterspace threats.

The announcement that Australia will have its own space command is a welcome one in this sense. All three of our armed forces depend on space-based technologies, and centralised coordination is sensible.

We also intend to increase our sovereign space capabilities, as outlined in the 2020 Strategic Defence Update, with A$7 billion dedicated to new space systems, mostly communications satellites. We need to be able to defend those satellites, and Defence needs to have centralised command and control of all government space operations. Australia also needs to be able to coordinate use of, access to, and protection of space with our allies.

Avoiding escalation

We should be extremely wary of designating space a “warfighting domain”. The US is the only country to adopt this nomenclature. It sends a deliberate signal to rivals that any point of conflict can now also be taken into space, or even begin in space.

The US Department of Defense asserts it is only responding to the actions of China and Russia, which have “weaponised space and turned it into a warfighting domain”. For China and Russia, of course, this statement and the creation of US Space Force justify ramping up their own space military programs. An escalating cycle with a potential for conflict in space is underway.

If Australia were to adopt the position that space is a warfighting domain, the most important country we would be sending a signal to would be China. We are far from having sufficient space capabilities to pick or win a fight with China in space. Adopting such a position could also be seen as a breach of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which states that space shall be used for “exclusively peaceful purposes”.

Competition is counterproductive

Following the lead of our other allies offers a better path. The NATO countries refused to describe space as a warfighting domain when they debated it at their space summit in 2019. They opted instead to designate space an “operational domain”.

The US Space Force is underpinned by a doctrine of “space superiority”, which is not something to which Australia can — or should — aspire. In fact, a study commissioned by the US Department of Defense itself concludes dominance in space is not crucial to US or allied defence.

This aligns with the arguments made by a range of global experts in a recent publication I co-edited, War and Peace in Outer Space. Seeking to dominate space militarily will likely lead to a counterproductive escalating cycle of competition. If we want to protect our space-based assets and those of our allies, we need to reduce the risk of an arms race, rather than incite one.

Australia should focus on its ability to become an effective diplomatic space power. A new centralised space command can be at the centre of this effort.

Cassandra Steer, Senior Lecturer, ANU College of Law; Mission Specialist, ANU Institute for Space, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.