Ian Hickie, University of Sydney

As Victorians face yet another long period of enforced lockdown, serious concerns are being raised about people’s capacity to comply with the new orders and the mental health impacts of such prolonged social isolation.

The risks of being dispirited, chronically stressed and socially disconnected are real and substantial. While the behavioural consequences of “lockdown fatigue” are becoming more obvious, the questions to be answered from a mental health perspective are:

- who is most likely to be harmed by a longer, more stringent lockdown?

- what are the public policy responses that are most likely to deliver real benefits?

Job losses and social disconnection

On the first issue, Sydney University’s Brain and Mind Centre has produced both place-based models and a provisional national simulation model to estimate the possible size of the impact of the pandemic on mental health and suicide rates, as well as identifying those who are most likely to be affected.

Prior to the recent spike in cases in Victoria, our most conservative estimates were a 14% increase in overall suicide rates due to COVID-19 restrictions and the subsequent social dislocation and economic fall-out nationally.

We also estimated at least a 25% increase in suicide rates in rural and regional areas with pre-existing high levels of unemployment and educational disadvantage.

The real drivers of these substantive health risks are job losses, social disconnection and, for young people, the availability of support for ongoing education and training.

Given the return to lockdown in Melbourne, we now expect to see much greater levels of uncertainty about job prospects — particularly in those industries like hospitality, tourism and the arts that were already devastated — as well as a more prolonged period of social disconnection.

For both of these factors, both the duration of the lockdown and the degree of uncertainty it generates really do matter.

What can government do to minimise harm to people?

Given the necessity to “act fast and go hard” to contain the spread of the virus, the harder question to answer is the second one: what can our political and social leaders do to minimise the impact on people’s mental health and well-being?

Top of the list is job certainty. Conceptually, JobKeeper is critical because it ties people to real workplaces, social contacts and their social identity.

However, in its initial application it missed many casual workers, women and young people. Each of these groups were massively affected by COVID-19 restrictions and are now facing even tougher long-term employment prospects.

Our model suggests JobKeeper, in its current or appropriately modified form, now needs to be in place until at least 2022. And our place-based approach suggests policy-makers need to think about how it can best function in Melbourne and surrounding districts.

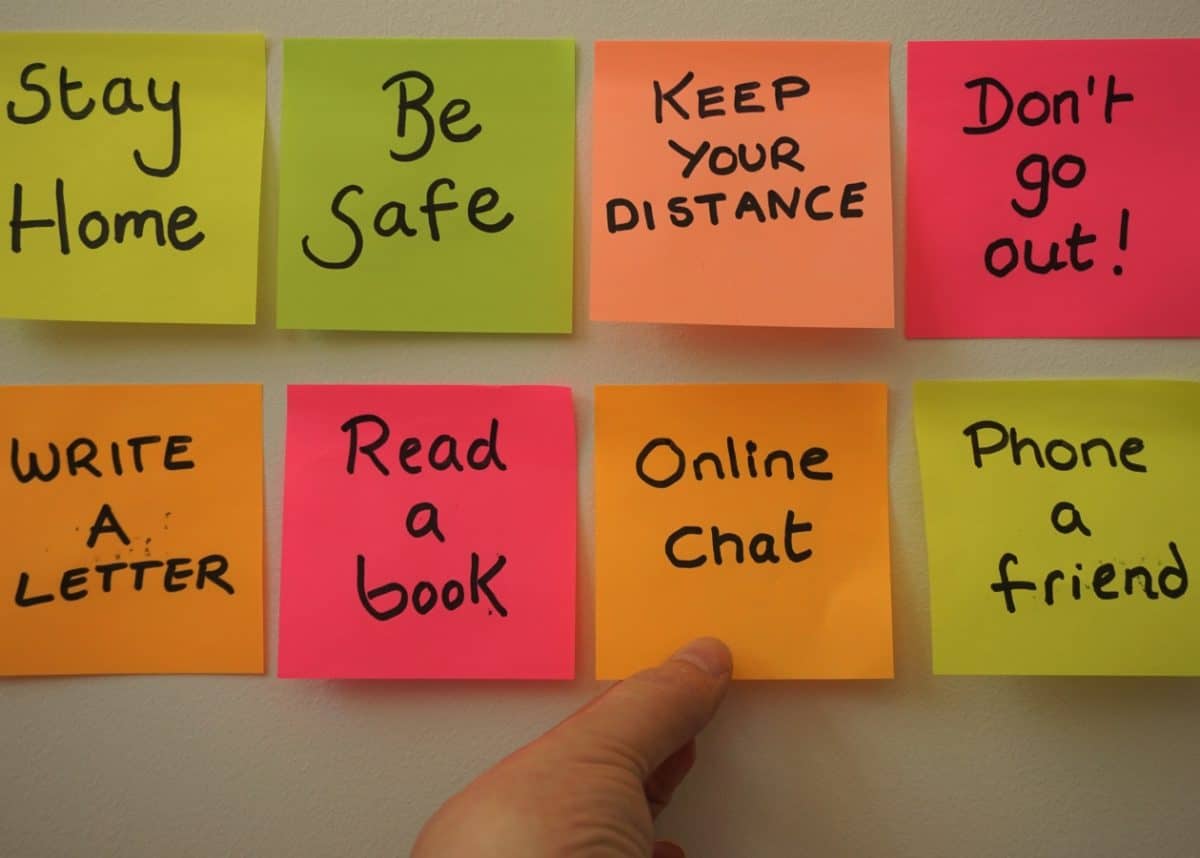

From a social connection perspective, all governments need to get their public messaging on track. An over-emphasis on top-down, law-and-order directives has limited and short-term utility for achieving the required behaviour changes. Often, it has the reverse effect to that intended.

What is really required are public health messages that engage people to be community-minded and active in their local settings to support and care for each other in really testing times.

The diverse faces and voices of genuine and trusted community leaders, elders, celebrities, sporting identities and young people — not simply politicians — are critical. These have much greater impact on two key outcomes: promoting best public behaviour and providing the necessary person-to-person support we all require.

Importantly, from a public mental health and health services perspective, any substantive actions rely heavily on close cooperation between the federal and Victorian governments. We cannot risk a retreat to the finger-pointing we saw during the Ruby Princess and quarantine hotel failures, and are now starting to see in the COVID-19 aged care crisis.

As indicated by the recent Victorian royal commission and the Productivity Commission report on mental health, both levels of government are responsible for the current deficiencies in our public mental health systems.

How to send the right message

From a public messaging perspective, people experiencing mental distress are being encouraged to use mental health hotlines or seek help from their family doctor or other mental health practitioners.

While these may seem to be straightforward and sensible messages, we have shown that simply increasing awareness without expanding the actual capacity of an already thinly stretched (if not broken) care system can have more negative outcomes.

What is really required are two clear actions. One is public messaging about supporting each other, and those who are distressed, within our families, workplaces, communities and churches throughout this period. The other is rapid action to fix key elements of the mental health system.

As demonstrated by Health Minister Greg Hunt’s actions in the early phases of the pandemic, it is possible to mobilise simultaneously both our private and public health services to respond to a national emergency.

That is now urgently required for mental health. We need to use our private health capacity to help public hospital emergency departments, and other acute care services, meet the increasing need for mental health services.

For instance, we could immediately make use of private hospital beds and clinics for those who have attempted suicide or are in need of urgent care, but who do not require admission to a public psychiatry unit.

While this need will soon likely become acutely obvious in Melbourne, we have already seen evidence in national surveys, and other state systems, of the escalating demand for these types of mental health services.

This has been most obvious for young people, who often do not easily connect with general practice doctors and typically present for care in a crisis situation.

Amid the chronic uncertainty that is now emblematic of the COVID-19 pandemic — often confusing government responses and the long-term economic and social impacts of the crisis — it is now time we respond to this looming mental health crisis cohesively, collectively and intelligently.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Ian Hickie, Professor of Psychiatry, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.