Marie Helweg-Larsen, Dickinson College

In recent years, the English-speaking world has found two Danish concepts, “pyt” and “hygge,” useful for dealing with anxiety and stress.

Now another Danish word – “samfundssind” – might help countries grapple with the pandemic.

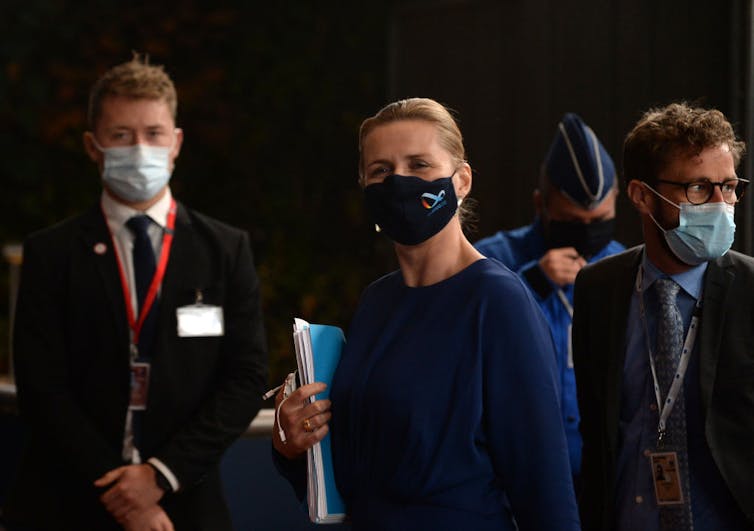

In March 2020, at the start of the pandemic, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen urged all Danes to show “samfundssind,” which means to consider the needs of society above your own. In English, it roughly translates to community spirit, civic engagement or civic-mindedness.

Since then, relative to the U.S. and the rest of Europe, Denmark has done quite well responding to the coronavirus, with low rates of infections and deaths and high rates of compliance with preventative guidelines. And research shows that – regardless of their gender or age – Danes are more concerned about infecting others than getting infected themselves.

Of course, the fact that Denmark has weathered the COVID-19 crisis well cannot be explained by any one factor. But as a Dane and a psychological scientist, I think it’s interesting that samfundssind seems to be related to societal values like trust and reciprocity, both of which are useful in combating a pandemic.

In society we trust

Before the pandemic, samfundssind was a relatively obscure word that was rarely, if ever, used. It first appeared in a Danish dictionary in 1936, and former Danish Prime Minister Thorvald Stauning included it in several speeches in the late 1930s imploring Danes to show community spirit as World War II was approaching. However, since Frederiksen used the word in her March speech, its usage in Denmark has spiked.

Although the word seems straightforward, it is also what linguists call an empty signifier because it can mean very different things to different people.

To some, samfundssind might mean people should follow most coronavirus guidelines. To others it means you should leave the house only if necessary. And still others believe it entails volunteering your time and money to help individuals affected by the coronavirus lockdown. But while the word is debated and discussed, these debates center on how to best achieve samfundssind, not whether it’s a good idea to consider societal needs above your own.

The concept of samfundssind seems to be related to what researchers call social capital. Members of societies that have high levels of social capital tend to be more trusting and reciprocal while feeling more connected to their fellow citizens – all attitudes that lend themselves to considering the needs of a community over your own.

Denmark is an individualistic society, and Danes rank as the most trusting in the world. They score highly in interpersonal trust as well as trust in institutions, such as the police and government. Denmark also has the world’s lowest levels of corruption.

High trust and low corruption mean people can reasonably expect they will benefit – and not be taken advantage of – by complying with COVID-19-related public recommendations or requirements, such as mask-wearing or working from home. And large studies from 25 European countries show that people living in regions with high institutional trust reduced their nonessential mobility – an indicator of social distancing – and had fewer COVID-19 deaths.

This finding is not unique to European countries. Research examining all counties in the United States found that people in communities with higher levels of social capital were more likely to stay at home as the pandemic unfolded. And this has been shown to have important outcomes. A study found that across Europe and within Italy, more social capital was associated with less mobility and fewer deaths.

Do gender-equal cultures have an advantage?

Danes might also be particularly amenable to appeals to samfundssind because the country values gender equality, which coincides with the fact that the nation scores low on cultural masculinity.

According to global research on culture and masculinity, societies that score high in masculinity – such as the U.S. – value competition, achievement and success. Societies that score low, such as Denmark, tend to be more oriented toward having a high quality of life, having meaningful work and caring for others. Conflicts tend to be settled by negotiation and compromise, and people value equality and solidarity.

Might a culture’s masculinity be a barrier to coronavirus precautions? It could, if enough people view taking precautions as weak or unmanly. And a large study of American men and women showed that having sexist beliefs strongly predicted lower concern about the pandemic, fewer precautionary behaviors, less support for coronavirus mitigation policies and an increased likelihood of contracting COVID-19.

Of course, all societies have some degree of samfundssind. If it’s measured by volunteering, donating money or helping a stranger, the U.S. does quite well. In fact, from 2009 to 2018, the U.S. ranked first and Denmark 16th on these measures.

Denmark does not possess some sort of secret sauce; many places in the U.S. and around the world have high levels of community engagement and support, which have led to more COVID-19 precautions and fewer deaths. There are U.S. communities that emphasize wearing a mask to care for neighbors or for the common good. Of course, this sort of messaging has been uneven, varying by town, city and state.

So what can you do to sustain or improve social capital in your local community?

Community engagement and volunteering can set a good example and strengthen communities by inspiring others to do the same. And if you ask people to “help me understand your perspective,” it’s possible to build trust; research shows that feeling understood can make us trust even people with whom we disagree.

With winter approaching and the pandemic showing no signs of slowing down, the impulse may be to retreat from the public health emergency and think only about ourselves and our own needs.

Samfundssind, however, can remind us to look outward, rather than inward.

Marie Helweg-Larsen, Professor of Psychology, the Glenn E. & Mary Line Todd Chair in the Social Sciences, Dickinson College