Tof Eklund, Auckland University of Technology

Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed series is one of the world’s best-selling video game series. Featuring settings ranging from Ancient Greece to the French revolution, Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla, released last month, takes the player into the mind of Evior, a viking raider who invades England.

Little about Assassin’s Creed is unique or new: many games feature historical settings, with or without time travel; there are countless third-person action and action role playing games — and the entire video game industry is preoccupied with making each game look and sound better than the last.

Even Assassin’s Creed’s signature stealth action gameplay, which allows the player to sneak past foes, set ambushes, and avoid notice … or eschew subtlety and rush in with a battle-cry, was first deployed by Eidos’ Thief: The Dark Project, in 1998.

First appearing in 2007, the franchise has spanned a dozen big budget PC and console games and inspired mobile tie-ins, comics, novels, board games, a film and a forthcoming Netflix live action series. So what’s its secret?

Part of it is the varied settings, stretching from Ancient Egypt to Renaissance Italy to the near future. But the real secret sauce, I’d argue, is in the motto of the in-game Assassins: “nothing is true, everything is permitted.”

Fast and loose with history

Assassin’s Creed plays fast and loose with history, simultaneously putting huge amounts of effort into the reproduction of historical architecture and styles while also staging an endless war between the Assassins, who fight for the freedom of all humanity, and the Templars, who believe peace can only be achieved when everyone is under their thumb.

The game enables the protagonist to put on an in-game headset known as an Animus device — an interactive history simulation. Rather than a time machine, the Animus uses the plot device of “genetic memory”. Protagonists can access their ancestors’ memories through their DNA to justify diversions not only from history but also possibility.

Like the play within the play in Hamlet, no-one really dies in an Animus simulation. This is an accepted fact of the plot. The goal isn’t to fix the past, but to learn from it, and apply that understanding within the world of the game. This gives players consistency in terms of the series’ world and overarching plot, while also allowing each game to explore a different historical setting.

Small twists on familiar game-play paired with diverse settings have kept fans hooked as the games moved from 15th century Venice to 18th century Boston, to 5th century BC Athens, and beyond. There’s a different chapter of the eternal war between the Assassins and the Templars to relive in each game, a new Animus simulation.

In an era where games, from indie hit Undertale to military shooter Spec Ops: The Line, ask players to consider the consequences of their actions, the Assassin’s Creed games ask the player to identify with groups often seen as “the bad guys”. Assassins, pirates, and invaders are the heroes here.

The player can engage in assassination, piracy and colonisation without hesitation because it’s only an Animus simulation.

A motto coined by Nietzsche

The actual historical Knights Templar are hard to get a grip on. Prominent in the 12th and 13th centuries, they fought brutally in, and profited greatly from, the Crusades. The order was later disbanded on false charges of heresy, with some burnt at the stake for confessions extracted under torture. More recently, they have grown popular with conspiracy theorists and white supremacists.

On the other hand, the Hashashins, the historical “Assassins” that inspired Assassin’s Creed, are infamous. This Ismaili sect was active at the same time as the Templars, but in Persia (modern-day Iran) and Syria, far from the Crusades. Often incorrectly described as a cult of pot-smoking killers without fear or remorse, the motto “nothing is true, everything is permitted” has been attributed to their founder, Hassan-i Sabbāh.

Slovakian-Italian author Vladimir Bartol collected rumours and created salacious details about the Hashashins in his 1938 novel Alamut. In it, stoned Assassins were carried to a hidden garden full of beautiful women and told they were seeing a vision of paradise.

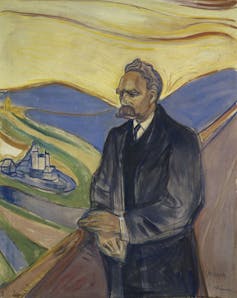

Assassin’s Creed took its motto from Bartol’s novel, but Bartol was actually quoting Friedrich Nietzsche. The first recorded instance of the the maxim “nothing is true, everything is permitted” is in Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathrusta(1883).

In this philosophical novel, Nietzsche develops his concept of the endless return, of living the same life over and over. That’s exactly what players do in the Assassin’s Creed games.

Valhalla

In Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla, the life you are living over is that of Evior. The player controls Layla Hassan, a modern-day Assassin, as she inhabits Evior, and he or she (the game lets you choose or periodically swap genders based on those genetic memories) re-stages the Norse invasion of the British Isles.

Evior’s back-story and motivations are textbook: s/he’s the orphan who needs to prove their worth, beat a nemesis and save their community. It’s a rubber stamp that leaves the player free to go i viking, raiding coastal settlements and camps, butchering any opposition, pillaging valuable goods, and using them to establish and fortify a Norse settlement in England.

Being an Assassin’s Creed game, the player also has the opportunity to infiltrate English cities, assassinating foes and rivals before quietly slipping away … or cutting a gory swath to freedom.

Fandom is all about wanting new experiences that make you feel the same way you did when you first became a fan. It’s a challenge for creators to provide something fresh and interesting but faithful to what fans already know and love.

Assassin’s Creed has worked this out: each version of the game is absolutely familiar, but makes that familiarity feel new.

Tof Eklund, Lecturer, Auckland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.