Erich Kisi, University of Newcastle and Alexander Post, University of Newcastle

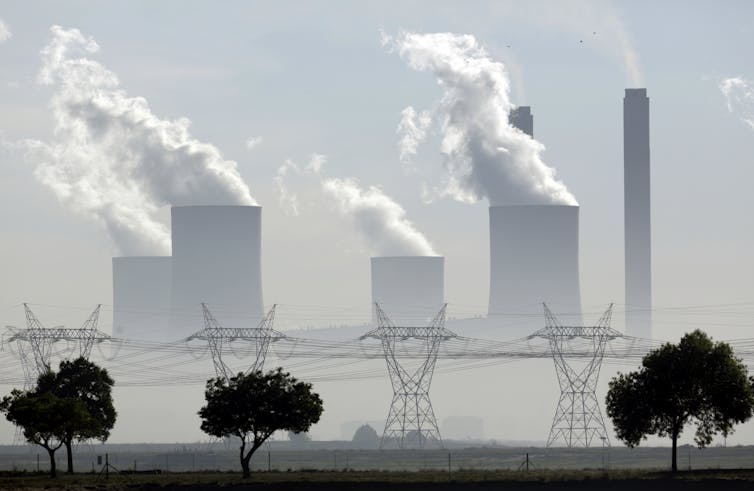

As climate change worsens, the future of fossil fuel jobs and infrastructure is uncertain. But a new energy storage technology invented in Australia could enable coal-fired power stations to run entirely emissions-free.

The novel material, called miscibility gap alloy (MGA), stores energy in the form of heat. MGA is housed in small blocks of blended metals, which receive energy generated by renewables such as solar and wind.

The energy can then be used as an alternative to coal to run steam turbines at coal-fired power stations, without producing emissions. Stackable like Lego, MGA blocks can be added or removed, scaling electricity generation up or down to meet demand.

MGA blocks are a fraction of the cost of a rival energy storage technology, lithium-ion batteries. Our invention has been proven in the lab – now we are moving to the next phase of proving it in the real world.

Why energy storage is important

Major renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power are “intermittent”. In other words, they only produce energy when the sun is shining and the wind is blowing. Sometimes they produce more energy than is needed, and other times, less.

So moving to 100% renewable electricity requires the energy to be “dispatchable” – stored and delivered on demand. Some forms of storage, such as lithium-ion batteries, are relatively expensive and can only store energy for short periods. Others, such as hydro-electric power, can store energy for longer periods, but are site-dependent and can’t just be built anywhere.

If our electricity grid is to become emissions-free, we need an energy storage option that’s both affordable and versatile enough to be rolled out at massive scale – providing six to eight hours of dispatchable power every night.

MGAs store energy for a day to a week. This fills a “middle” time frame between batteries and hydro-power, and allows intermittent renewable energy to be dispatched when needed.

How our invention works

In the next two decades, many coal-fired power stations around the world will retire or be decommissioned, including in Australia. Our proposed storage may mean power stations could be repurposed, retaining infrastructure and preventing job losses.

For coal stations to use our technology, the furnace and boiler must be removed and replaced by a storage unit containing MGA blocks.

MGA blocks are 20cm x 20cm x 16cm. They essentially comprise a blend of metals – some that melt when heated, and others that don’t. Think of a block as like a choc-chip muffin heated in a microwave. The muffin consists of a cake component, which holds everything in shape when heated, and the choc chips, which melt.

The blocks don’t just store energy – they heat water to create steam. In an old coal plant, this steam can be used to run turbines and generators to produce electricity, rather than burning coal to produce the same effect. https://www.youtube.com/embed/bt-Ux48Aohw?wmode=transparent&start=0 Courtesy University of Newcastle.

To create the steam, the blocks can be designed with internal tubing, through which water is pumped and boiled. Alternatively, the blocks can interact with a heat exchanger – a specially designed system to heat the water.

Old coal plants could run on renewable energy that would otherwise be switched off during periods of oversupply in the middle of the day (in the case of solar) or times of high wind (wind energy).

Our research has shown the blocks are a fraction the cost of a lithium battery of the same size, yet produce the same amount of energy.

Proving MGA blocks in the real world

Our team perfected the novel material through research at the University of Newcastle between 2010 and 2018. Last year we formed a company, MGA Thermal, and are focused on commercialising the technology and conducting real-world projects.

In July this year, MGA Thermal received a A$495,000 grant from the federal Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, to establish a pilot manufacturing plant in Newcastle, New South Wales. This project is due to start operating in the second half of next year. The goal is to begin manufacturing a commercial quantity of MGA blocks economically, at scale, for large demonstration projects.

MGA Thermal have partnered with a Swiss company, E2S Power AG, to test the technology in the rapidly changing coal-fired power industry in Europe. Beginning next year, the testing will include retrofitting a functioning coal power plant with MGA storage. This will also verify the economic case for the technology.

We are aiming for a cost of storage of A$50 per kilowatt hour, including all surrounding infrastructure. Currently, lithium-ion batteries cost around A$200 per kilowatt hour, with added costs if energy is to be exported to the electricity grid.

So what are the downfalls? Well, MGA does have a much slower response time than batteries. Batteries respond in milliseconds and are excellent at filling short spikes or dips in supply (such as from wind turbines). Meanwhile MGA storage has a response time above 15 minutes, but does have much longer storage capacity.

A combination of all three options – batteries, MGA/thermal storage and hydro – would provide large-scale energy storage that can still respond quickly to fluctuating renewable supply. https://www.youtube.com/embed/y3uwcBLBv-o?wmode=transparent&start=0 Courtesy University of Newcastle.

Safe and recyclable

MGA blocks are safe and non-toxic – there is no risk of explosion or leakage, unlike some other fuels.

The blocks can also be recycled. They are expected to last 25-30 years, then can be easily separated into their individual materials – to be made into new blocks, or recycled as raw materials for other uses.

Like any new technology, MGA blocks must be financially proven before they’re accepted by industry and used widely in commercial projects. The first full-scale demonstrations of the technology are on the horizon. If successful, they could allow coal-fired power plants to be used cleanly, and provide hope for the future of coal workers.

Erich Kisi, Professor of Engineering , University of Newcastle and Alexander Post, Conjoint Lecturer, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.