After nearly two years of a facilitated conciliation process initiated under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Australia and Timor Leste have finally reached agreement on a maritime boundary in the Timor Sea.

The treaty, signed at the UN in New York by Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop and Agio Pereira for Timor, will enter into force once all relevant domestic processes have been completed in Canberra and Dili.

This is the latest development in the saga of the Timor Sea, which has been contested for more than 45 years by Australia, Portugal, Indonesia and Timor Leste.

Ownership and control of significant oil and gas reserves, some of which remain undeveloped, are at the centre of the dispute. This partly explains why, despite previous treaties, there has never been a conclusive settlement of the maritime boundary.

The 2018 treaty seeks to permanently settle the Australia/Timor Leste maritime boundary, albeit with the potential for future adjustments subject to negotiations between Timor and Indonesia.

A long time coming

Since the 1970s, Australia has been engaged in negotiations first with Portugal, then Indonesia, and finally Timor Leste over the maritime boundary. Portugal rebuffed Australian approaches in the early 1970s, mindful of developments in maritime law that promised them a better deal.

Indonesia, which occupied Timor from 1975, was more willing to negotiate. A joint development zone was agreed on that broadly shared oil and gas revenue on a 50/50 basis, but set aside a permanent maritime boundary for future settlement.

That arrangement collapsed following Indonesia’s 1999 withdrawal from Timor, and was replaced in 2002 by the Timor Sea Treaty between Australia and the newly independent Timor Leste.

However, the Timor Sea Treaty was again based on a joint development regime –though with a 90/10 revenue split in favour of Timor – and negotiations on a permanent maritime boundary were set aside for up to 40 years.

The treaty also did not satisfactorily deal with the Greater Sunrise oil and gas field in the north east quadrant. While a subsequent 2003 unitisation agreement sought to provide some commercial certainty for the multinationals wanting to develop the field, Dili remained firmly of the view that it was getting a bad deal.

In particular, the generation of Timor’s leaders who led its independence movement placed great importance on the new country having settled land and maritime borders. That the Timor Sea boundary with Australia was not settled remained contentious in Dili. The situation was exacerbated by allegations of Australian spying during treaty negotiations and a Greater Sunrise revenue split that favoured Australia.

Key features

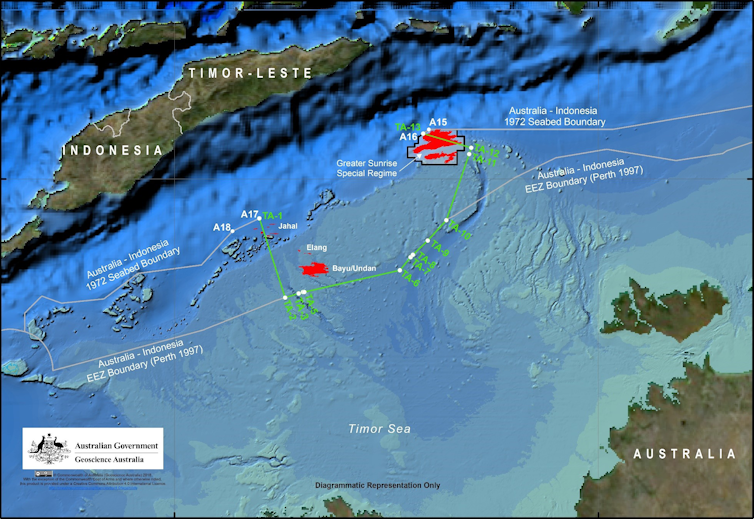

The 2018 treaty contains six prominent features. First, it provides for a southern boundary between Timor Leste and Australia that approximates a mid-way between relevant coastal features. This is consistent with the modern law of the sea.

Second, there is a straight line western lateral boundary that runs from the western terminus of the 1972 Australian Indonesian Seabed Boundary south to the median line.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

Third, the eastern lateral boundary comprises a number of segments that extend much further to the east and north east than the 2002 treaty, ultimately giving Timor Leste much greater entitlements over the Greater Sunrise field.

Fourth, a Greater Sunrise Special Regime is created in which the two countries agree to share the upstream revenue either on a 80/20 basis in favour of Timor, if processing occurs by way of a pipeline to an Australian LNG processing plant, or 70/30 in favour of Timor if a pipeline runs to Timor.

Fifth, Timor gains 100% access to the future upstream revenue of the existing oil and gas fields that were previously part of the 2002 Joint Petroleum Development Area.

Finally, taking into account these new arrangements will ultimately need to accommodate any maritime boundaries that Timor may negotiate with Indonesia, there is some capacity for adjustment of the eastern and western lateral boundary lines, though only after the commercial depletion of seabed resources in the area.

Unique, but still unresolved

The conciliation process has yielded a unique treaty. It is the first of its type that not only involved the two states, but also the Greater Sunrise Joint Venture partners, including Woodside, Conoco Phillips, Shell, and Osaka Gas.

Timor initiated the conciliation, engaging an independent third party in an effort to break the maritime boundary impasse. It succeeded in getting Australia to abandon its long held opposition to a permanent Timor Sea maritime boundary, and has been able to substantially modify the development regime for Greater Sunrise.

![]() Notwithstanding these achievements, some matters remain unresolved, including the location of the LNG processing plant. Whether the plant is located in Australia or Timor is ultimately a commercial decision, but could become the source of ongoing bickering given the significant downstream benefits at stake and implications for Timor’s economic future.

Notwithstanding these achievements, some matters remain unresolved, including the location of the LNG processing plant. Whether the plant is located in Australia or Timor is ultimately a commercial decision, but could become the source of ongoing bickering given the significant downstream benefits at stake and implications for Timor’s economic future.

______________________________

By Donald R. Rothwell, Professor, ANU College of Law, Australian National University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

TOP IMAGE: Shutterstock / The Conversation