The chances of an El Niño developing late in 2018 have increased and this week the Bureau moved to El Niño ALERT. This means that model outlooks and observations indicate there is approximately a 70% chance that El Niño will develop in the coming months. Current patterns in the Pacific are similar to the early stages of past El Niño, with warm water shifting east towards South America.

We’re also seeing indications a positive Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) has likely started, in which warmer waters near Africa drag moisture away from Australia. El Niño and positive IOD events typically mean below-average spring rainfall in central and southern Australia, and a drier start to the wet season in Queensland and the Northern Territory.

The development of either would favour continued dry weather, and increase the likelihood that widespread drought relief will be delayed until 2019. Higher than average temperatures, heatwaves, and more severe bushfire weather are also more likely during El Niño and positive IOD events.

A dry year so far

September 2018 was a very dry month, adding to low rainfall seen across many parts of Australia so far this year. September 2018 was not only the driest September in 119 years of record for Australia, but it was also the second-driest for any month of the year (behind only April 1902).

Rainfall for the year to date has been exceptionally low over the mainland southeast, with much of the region experiencing totals in the lowest 10% of records for January–September. Many locations in eastern New South Wales, eastern Victoria, and southeast Queensland have received about 400 mm less rainfall than they usually would have by this time of the year.

Bureau of Meterology

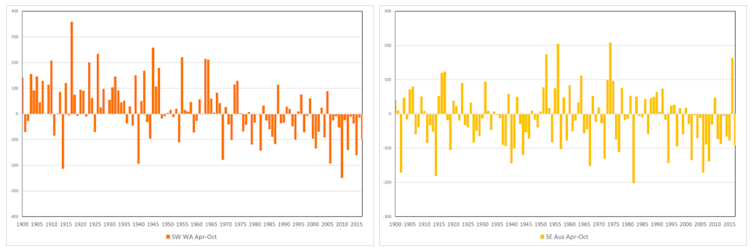

Much of southern Australia has experienced a persistent rainfall decline spanning several decades, which is adding to drought stress by drying the landscape.

Southwest Western Australia has experienced significantly lower cool season (April to October) rainfall since the mid-1970s, compared to observations since 1900, while for the southeast the drop has been more recent, emerging in the mid-1990s. These rainfall declines have been linked to circulation changes in the southern hemisphere influenced by the increase in greenhouse gases.

These rainfall changes have also been accompanied by much larger reductions in streamflow, particularly in the southwest of Australia where high flows have become much less frequent.

Bureau of Meteorology

And it’s also been unusually warm

Low rainfall has also been accompanied by very high daytime temperatures so far this year. Of course, Australian temperatures are warming in line with global trends, but in individual years variations which are likely to be largely natural (such as droughts) may add to or subtract from the broader trends.

Historically, droughts have often brought hot conditions, and this has been borne out in 2018. Maximum temperatures for January to September were the warmest on record for the Murray–Darling Basin and New South Wales, with neighbouring regions also much warmer than average.

These extremely warm days, combined with extremely low rainfall, have caused an intense drying of the Australian landscape in 2018, resulting in an early start to the bushfire season in New South Wales and Victoria, where damaging fire were observed as early as late winter.

So how might the year end?

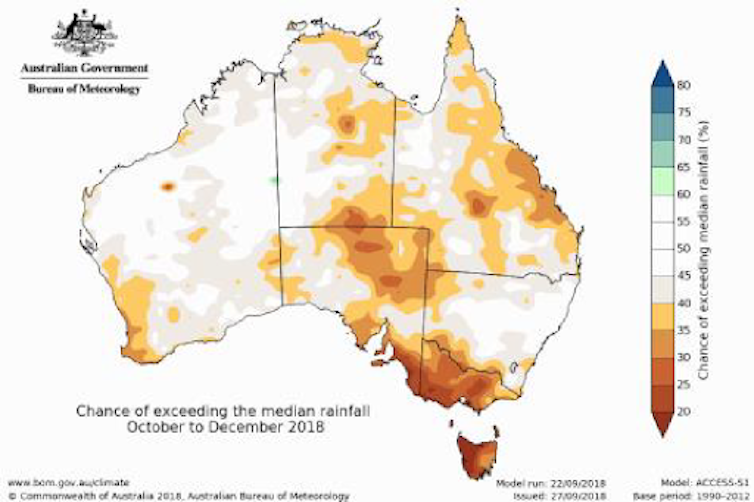

Like all Australians, the Bureau hopes farmers and those suffering through drought get the rainfall they need, but unfortunately, the outlook indicates dry conditions are likely to continue for some time.

Large parts of southern and eastern Australia are likely to see a drier than average end to the year, though odds favouring drier than average conditions tend to moderate as we head towards summer. Most of the country is likely to see a dry October, though local heavy falls can occur against a backdrop of broadly suppressed rainfall.

Bureau of Meteorology

While some parts of New South Wales and southeastern Queensland have received very welcome rainfall in the first days of October, rainfall has been below average over much of over eastern Australia for so long (since early 2017) that this rainfall event hasn’t been enough to break the drought.

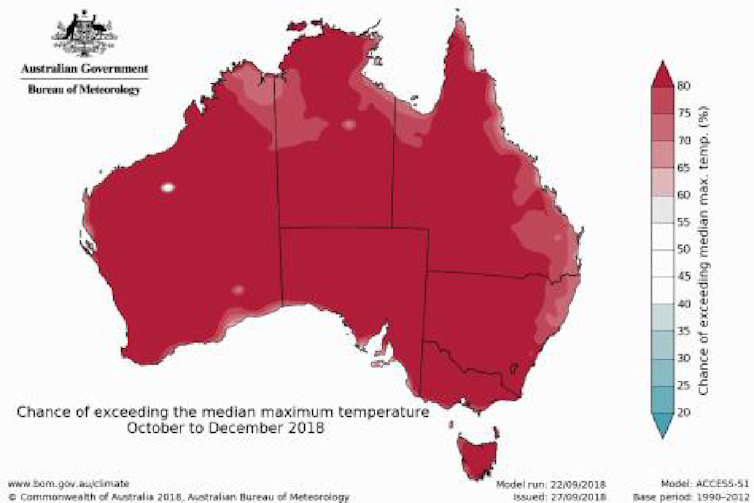

Looking at temperature, outlooks show a very high chance of warmer than average days and nights through to the end of 2018. Considering the year so far has already been very warm, this means 2018 has the potential to rank as another significant warm year. Seven of Australia’s ten warmest years have occurred since 2005, with just one cooler than average year in the last decade (2011), highlighting how warmer than average temperatures now dominate Australia’s climate.![]()

Bureau of Meteorology

__________________________________________________________

By Skie Tobin, Climatologist, Australian Bureau of Meteorology; Catherine Ganter, Senior Climatologist, Australian Bureau of Meteorology, and Robyn Duell, Senior Climatologist, Australian Bureau of Meteorology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

TOP IMAGE: Drought (_Marion via Pixabay)