Jerry Davis, University of Michigan

Coinbase’s plan to go public in April highlights a troubling trend among tech companies: Its founding team will maintain voting control, making it mostly immune to the wishes of outside investors.

The best-known U.S. cryptocurrency exchange is doing this by creating two classes of shares. One class will be available to the public. The other is reserved for the founders, insiders and early investors, and will wield 20 times the voting power of regular shares. That will ensure that after all is said and done, the insiders will control 53.5% of the votes.

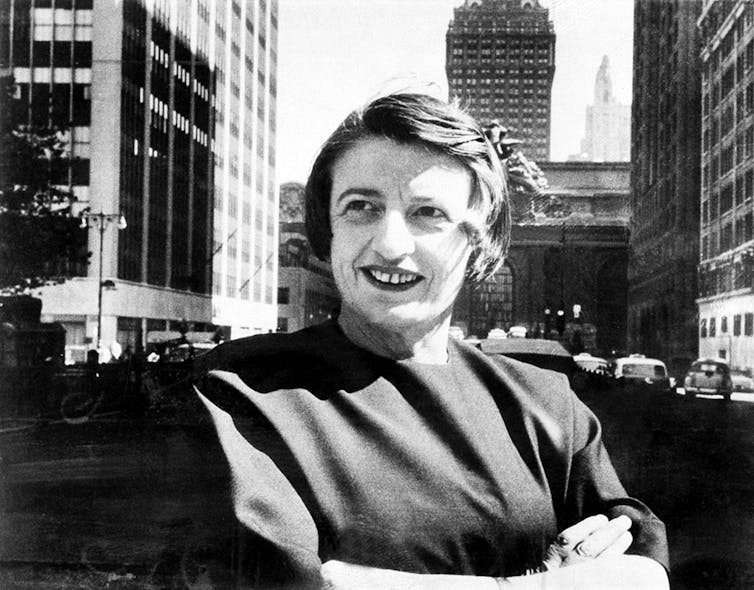

Coinbase will join dozens of other publicly traded tech companies – many with household names such as Google, Facebook, Doordash, Airbnb and Slack – that have issued two types of shares in an effort to retain control for founders and insiders. The reason this is becoming increasingly popular has a lot to do with Ayn Rand, one of Silicon Valley’s favorite authors, and the “myth of the founder” her writings have helped inspire.

Engaged investors and governance experts like me generally loathe dual-class shares because they undermine executive accountability by making it harder to rein in a wayward CEO. I first stumbled upon this method executives use to limit the influence of pesky outsiders while working on my doctoral dissertation on hostile takeovers in the late 1980s.

But the risks of this trend are greater than simply entrenching bad management. Today, given the role tech companies play in virtually every corner of American life, it poses a threat to democracy as well.

All in the family

Dual-class voting structures have been around for decades.

When Ford Motor Co. went public in 1956, its founding family used the arrangement to maintain 40% of the voting rights. Newspaper companies like The New York Times and The Washington Post often use the arrangement to protect their journalistic independence from Wall Street’s insatiable demands for profitability.

In a typical dual-class structure, the company will sell one class of shares to the public, usually called class A shares, while founders, executives and others retain class B shares with enough voting power to maintain majority voting control. This allows the class B shareholders to determine the outcome of matters that come up for a shareholder vote, such as who is on the company’s board.

Advocates see a dual-class structure as a way to fend off short-term thinking. In principle, this insulation from investor pressure can allow the company to take a long-term perspective and make tough strategic changes even at the expense of short-term share price declines. Family-controlled businesses often view it as a way to preserve their legacy, which is why Ford remains a family company after more than a century.

It also makes a company effectively immune from hostile takeovers and the whims of activist investors.

Checks and balances

But this insulation comes at a cost for investors, who lose a crucial check on management.

Indeed, dual-class shares essentially short-circuit almost all the other means that limit executive power. The board of directors, elected by shareholder vote, is the ultimate authority within the corporation that oversees management. Voting for directors and proposals on the annual ballot are the main methods shareholders have to ensure management accountability, other than simply selling their shares.

Recent research shows that the value and stock returns of dual-class companies are lower than other businesses, and they’re more likely to overpay their CEO and waste money on expensive acquisitions.

Companies with dual-class shares rarely made up more than 10% of public listings in a given year until the 2000s, when tech startups began using them more frequently, according to data collected by University of Florida business professor Jay Ritter. The dam began to break after Facebook went public in 2012 with a dual-class stock structure that kept founder Mark Zuckerberg firmly in control – he alone controls almost 60% of the company.

In 2020, over 40% of tech companies that went public did so with two or more classes of shares with unequal voting rights.

This has alarmed governance experts, some investors and legal scholars.

Ayn Rand and the myth of the superhuman founder

If the dual-class structure is bad for investors, then why are so many tech companies able to convince them to buy their shares when they go public?

I attribute it to Silicon Valley’s mythology of the founder –- what I would dub an “Ayn Rand theory of corporate governance” that credits founders with superhuman vision and competence that merit deference from lesser mortals. Rand’s novels, most notably “Atlas Shrugged,” portray an America in which titans of business hold up the world by creating innovation and value but are beset by moochers and looters who want to take or regulate what they have created.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Rand has a strong following among tech founders, whose creative genius may be “threatened” by any form of outside regulation. Elon Musk, Coinbase founder Brian Armstrong and even the late Steve Jobs all have recommended “Atlas Shrugged.”

Her work is also celebrated by the venture capitalists who typically finance tech startups – many of whom were founders themselves.

The basic idea is simple: Only the founder has the vision, charisma and smarts to steer the company forward.

It begins with a powerful founding story. Michael Dell and Zuckerberg created their multibillion-dollar companies in their dorm rooms. Founding partner pairs Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak and Bill Hewlett and David Packard built their first computer companies in the garage – Apple and Hewlett-Packard, respectively. Often the stories are true, but sometimes, as in Apple’s case, less so.

And from there, founders face a gantlet of rigorous testing: recruiting collaborators, gathering customers and, perhaps most importantly, attracting multiple rounds of funding from venture capitalists. Each round serves to further validate the founder’s leadership competence.

The Founders Fund, a venture capital firm that has backed dozens of tech companies, including Airbnb, Palantir and Lyft, is one of the biggest proselytizers for this myth, as it makes clear in its “manifesto.”

“The entrepreneurs who make it have a near-messianic attitude and believe their company is essential to making the world a better place,” it asserts. True to its stated belief, the fund says it has “never removed a single founder,” which is why it has been a big supporter of dual-class share structures.

Another venture capitalist who seems to favor giving founders extra power is Netscape founder Marc Andreessen. His venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz is Coinbase’s biggest investor. And most of the companies in its portfolio that have gone public also used a dual-class share structure, according to my own review of their securities filings.

Bad for companies, bad for democracy

Giving founders voting control disrupts the checks and balances needed to keep business accountable and can lead to big problems.

WeWork founder Adam Neumann, for example, demanded “unambiguous authority to fire or overrule any director or employee.” As his behavior became increasingly erratic, the company hemorrhaged cash in the lead-up to its ultimately canceled initial public offering.

Investors forced out Uber’s Travis Kalanick in 2017, but not before he’s said to have created a workplace culture that allegedly allowed sexual harassment and discrimination to fester. When Uber finally went public in 2019, it shed its dual-class structure.

There is some evidence that founder-CEOs are less gifted at management than other kinds of leaders, and their companies’ performance can suffer as a consequence.

But investors who buy shares in these companies know the risks going in. There’s much more at stake than their money.

What happens when powerful, unconstrained founders control the most powerful companies in the world?

The tech sector is increasingly laying claim to central command posts of the U.S. economy. Americans’ access to news and information, financial services, social networks and even groceries is mediated by a handful of companies controlled by a handful of people.

Recall that in the wake of the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection, the CEOs of Facebook and Twitter were able to eject former President Donald Trump from his favorite means of communication – virtually silencing him overnight. And Apple, Google and Amazon cut off Parler, the right-wing social media platform used by some of the insurrectionists to plan their actions. Not all of these companies have dual-class shares, but this illustrates just how much power tech companies have over America’s political discourse.

One does not have to disagree with their decision to see that a form of political power is becoming increasingly concentrated in the hands of companies with limited outside oversight.

Jerry Davis, Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford and Professor of Management and Sociology, University of Michigan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.