Steven P. Millies, Catholic Theological Union

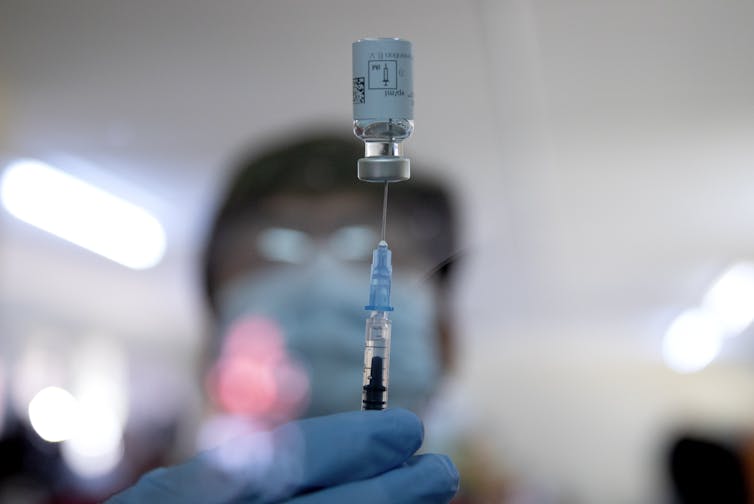

Questions about whether the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine is morally acceptable to observant Catholics due to concerns over use of fetal stem cells in its development have brought the deep divisions within the Catholic Church into public view.

On Feb. 26, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans released a statement saying that the Johnson & Johnson vaccine is “morally compromised as it uses the abortion-derived cell line in development and production of the vaccine as well as the testing.” Four days later, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, the national body of Catholic bishops, stated, “if one has the ability to choose a vaccine, Pfizer or Moderna’s vaccines should be chosen over Johnson & Johnson’s.”

A few days later, Kevin Rhoades, one of the bishops who issued the statement, attempted to clarify things when he said, “There’s no moral need to turn down a vaccine, including the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, which is morally acceptable to use.” But only hours later, the bishop of Bismarck, North Dakota said the “Johnson & Johnson vaccine is morally compromised and therefore [it is] unacceptable for any Catholic physician or health care worker to dispense and for any Catholic to receive due to its direct connection to the intrinsically evil act of abortion.”

These statements have confused many Catholics and others outside the church, too. They have also led to concerns over people being discouraged from getting vaccinated.

As a political scientist who also works in theology, I have studied America’s growing political polarization, especially related to the Catholic Church, for many years. The current controversy about vaccines needs to be seen in that context.

Abortions and fetal tissue

To be clear, none of the vaccines directly uses fetal tissue. Embryonic stem cells can turn into any type of cell and are often used in medical research. Embryonic stem cells used in medical research are usually clones, thousands of generations removed from the original cell. Researchers can turn these cloned cells into any type of cell. All vaccines, whether Moderna, Pfizer or Johnson & Johnson, rely on stem cells, harvested decades ago from early stage aborted fetuses, for the laboratory testing of vaccines. This research is extensively regulated.

The Johnson & Johnson vaccine is somewhat different from the other vaccines because stem cells were used not only to test the vaccine in the lab, but also to produce it. Johnson & Johnson said in a statement recently: “Several types of cell lines created decades ago using fetal tissue exist and are widely used in medical manufacturing but the cells in them today are clones of the early cells, not the original tissue.”

However, Catholic moral theology obliges believers to be concerned that they might benefit from the abortions that resulted in those initial fetal stem cells.

Catholic moral theology

Faithful Catholics feel morally bound by the teaching of the Catholic Church that abortion is an intrinsic moral evil – an act which never can have a justification.

The moral principle involved is called “cooperation in evil.” To understand cooperation, we might imagine the getaway driver in a bank robbery. The driver might not actually rob the bank or even approve of the robbery. Yet, driving the robbers away assures the robbery’s success. The driver has cooperated.

Cooperation can take many shapes. If I discover that a bank robber has used stolen money to buy me an expensive gift, I have profited from the robbery if I keep the gift and do not report the robber to authorities.

This example is a little more like the case of fetal stem cells. To accept a benefit from what is deemed an evil act even at some remote distance can be to cooperate with it in some situations.

Rarely are our moral choices so clear as these examples, however. It is shockingly easy to cooperate in evil in the course of daily life. Catholic moral principles can often help Catholics weigh and balance competing moral priorities.

‘Morally acceptable’

Because the benefit obtained from stem cells that resulted from an abortion is a little bit more direct in the case of Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine, Catholics have been more hesitant.

Still, weighing and balancing everything that is at stake, most Catholic bioethicists, many Catholic bishops and Pope Francis have found that receiving any of the vaccines is “morally acceptable,” which was the judgment of the Pontifical Academy for Life, a Vatican office that studies bioethical issues.

But there have been prominent Catholic bishops and other Catholic voices who have said that the Johnson & Johnson vaccine may not be administered by, or received by, a Catholic.

Divisions in church

The popular image of the Catholic Church is that it is a top-down organization, one unified voice with one central authority. It is this sensibility that gives rise to media headlines about the Catholic Church’s moral concerns over the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

In one dimension, this is an accurate description of the church, which is a monarchy and does have one central authority in Rome. But in reality, the Catholic Church is more complex and much more fragmented than those outside often can see.

Jurisdictional distinctions are important in Catholicism. The Catholic Church is both a global institution and a highly local one.

The Catholic Church divides the globe into dioceses. Each diocese is overseen by a bishop who is the authoritative pastor and teacher of doctrine for his own diocese.

Catholic bishops enjoy a tremendous amount of autonomy inside their own dioceses. All of them are subject to the authority of the pope. But none of them is bound by anything another bishop says. Not even the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops has authority over any individual bishop.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

The statement from the Archdiocese of New Orleans is binding only on Catholics in New Orleans. So is the case with the statements from bishops of Lexington and San Diego – they have authority only within their diocese. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ statement is intended to give guidance to Catholics around the United States, but has no particular authority over any individual Catholic.

Here’s what the pope has said

To understand what is happening around the vaccine, context is important. Prior to recent decades, public disagreements among senior Catholic Church leaders like these were unheard of.

But public airings of pointed disagreements have been becoming more and more common over the last 25 years. In 2020, bishops were divided over how to deal with a Biden presidency. And this year, that division reemerged following an Inauguration Day statement from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops that described how the Biden administration’s policies could “advance moral evils and threaten human life and dignity.” Several church leaders later expressed public criticism over the statement. Such disagreements are a symptom of the polarization that is roiling the world all around the Catholic Church. This polarization is dividing Catholics, too.

Caught in the middle of all of this are ordinary, faithful Catholics who simply want to do the right thing. For that, the advice of Pope Francis would be a good place to start. Pope Francis has said that the role of the church, its bishops and priests is to “inform consciences, not replace them.”

Catholic Theological Union is a member of the Association of Theological Schools. The ATS is a funding partner of The Conversation US.

Steven P. Millies, Associate Professor of Public Theology and Director of The Bernardin Center, Catholic Theological Union

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.