China started with a warning that Australia’s position might spark a Chinese consumer boycott.

It’s now threatening tariffs on Australian barley that would include a “dumping margin” of up to 73.6% and a “subsidy margin” of up to 6.9%.

The subsidy claims are thought to refer to drought support measures and Australia’s diesel fuel tax rebate.

Together with the dumping tariff (a penalty for allegedly selling barley too cheaply) they would amount to a tariff of 80.5%, effectively putting an end to Australian barley sales to China.

Australia’s exporters and the government have been given ten days to respond.

There’s more to it than barley

A series of decisions and reactions to events that were perceived as anti-China has pushed relations between Australia and China to the verge of a historic low.

Each time, China has urged Australia to reconsider its position and on some occasions has threatened to retaliate.

Recent examples include Australia’s exclusion of Huawei from its 5G network for fear of the influence of the Chinese government on its activities, and the COVID-19 travel ban which singled out China when introduced on February 1 even though by then the virus had spread to other countries.

China targeted barley for good reasons.

Why barley?

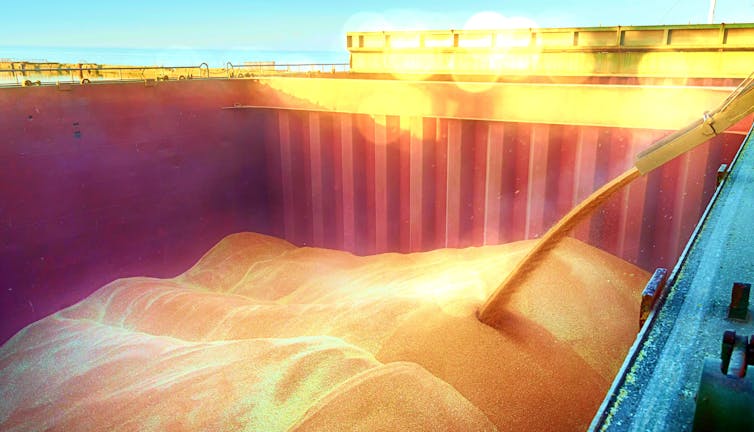

China is Australia’s largest market for barley exports.

Between 2015 and 2018, China imported, on average, 4.6 million tonnes or A$1.3 billion of Australian barley accounting for over 70% of Australia’s barley exports.

A tariff increase would have significant impacts on Australia’s barley producers who are scattered over several Australian states, putting considerable political pressure on the Australian government.

China meanwhile has other suppliers from which to choose. It can restrict imports of Australian barley while continuing to buy barley from elsewhere.

And contrary to the claims by Trade Minister Simon Birmingham, the Chinese tariffs are not legally unjustifiable.

The tariffs would be the result of an ongoing anti-dumping investigation into barley exported from Australia that China’s Ministry of Commerce initiated on November 19, 2018.

Anti-dumping measures, which seek to prevent lower-priced imports from causing injury to domestic industries, are permitted under the rules of the World Trade Organisation and the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement.

Australia itself has been one of the most frequent users of anti-dumping measures, particularly against China.

The 2015 China-Australia Free Trade Agreement cut Chinese tariffs on Australian barley exports to zero. But it included an exemption: anti-dumping provisions that could increase the tariffs to any rate.

At the start of the 2018 investigation, China’s barley industry requested an anti-dumping tariff of 56.14%. The proposed rate was increased to 73.6% after investigations by Chinese authorities.

That is the investigation that authorities will finalise by May 19, the one started eighteen months ago, on November 19, 2018.

It began long before COVID-19, motivated among other things by Australia’s enthusiastic use of anti-dumping measures on products such as Chinese steel.

But its timing has made it a useful way to push Australia to change its anti-China position on an inquiry and on other matters in the future.

Since China’s investigation began, Chinese customers have become “very cautious about buying Australian barley” in the assessment of the Canadian barley industry which has benefited by selling Chinese customers barley they once would have sourced from Australia.

The actual imposition of the tariff will hurt more.

The only legal avenue for Australia to challenge it would be the World Trade Organisation’s dispute settlement mechanism which had been brought to a near halt by the United States refusing to appoint appellant judges and would in any case take years to process without a guaranteed win.

Even if Australia is successful, China may simply begin a reinvestigation which may maintain the original decision.

What’s the best way out?

Australia needs to take actions to ease the tensions and strengthen economic relationship with China.

Abundant evidence has shown that China will remain an irreplaceable Australian customer meaning it would be neither possible nor wise for Australia to decouple from China.

Diplomatic actions, such as the appointment of a special Australian China envoy, will be desirable but not sufficient. Australia has to ensure its future policy decisions are not biased against China.

To help, Australia could consider a gradual reduction of travel restrictions on China based on China’s success in fighting the virus and renewed more realistic assessment of the potential health risks posed by Chinese travellers.

Australia needs to be cautious in foreign investment decisions which have already been regarded as discriminatory against China before the pandemic.

The pandemic brought forth temporary changes of Australia’s foreign investment rules, making all proposals the subject of Foreign Investment Review Board scrutiny regardless of size.

While the changes applied to foreign investors from all countries, Australia’s decision to reject two from China has raised concerns about whether the decisions have been compromised by anti-China politics.

Instead of direct rejection, Australia might have been better off offering to approve them under conditions sufficient to address national interest concerns.

Australia should reassess its position on the 5G network to ensure it focuses on risks associated with 5G equipment rather than the nationality of 5G suppliers, as have Britain and the European Union.

These actions would signal a strong political will to repair the relationship that would build the foundation for the two economies to broaden and deepen economic engagement for mutual benefits.

Weihuan Zhou, Senior Lecturer and member of Herbert Smith Freehills CIBEL Centre, Faculty of Law, UNSW Sydney, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.