China wants to be a friend to the Pacific Photo by Macau Photo Agency on Unsplash

Ian Kemish, The University of Queensland

The photo of the Chinese ambassador to Kiribati walking on the backs of schoolboys caused a storm on social media earlier this month. Some saw it as a symbol of China’s sinister intentions in the Pacific and others argued it reflected local customs which should be respected.

The Chinese foreign ministry said in its defence,

We fully respect local customs and culture when interacting with the Pacific countries. When in Rome, do as the Romans do.

Let’s set aside the argument over the incident itself. I’d just note in passing there were several occasions when, as a senior Australian representative in the region, I had to quietly back away from ceremonies where my involvement could have sent the wrong signal.

The foreign ministry’s statement raises a more important point. As a genuine regional partner, it’s not enough for China to “do as the Romans do”. Those who aspire to a meaningful partnership with the Pacific also need to be clear about what they stand for themselves.

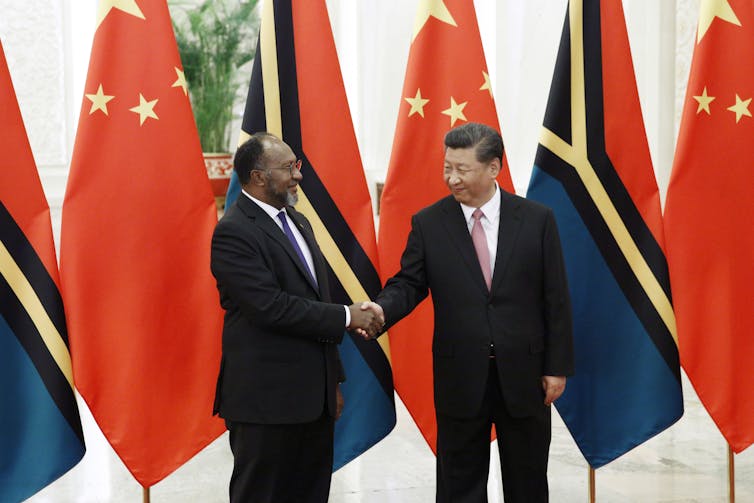

What then, does China stand for in the Pacific? Does it really have what it takes to be a constructive, long-term partner for the region?

There’s been no clear answer to the first question from Beijing, apart from broad statements about “mutual respect and common development”.

China maintains it does not have strategic interests in the region, and that its engagement there is simply a function of its growth.

Many observers point to its hunger for resources, however, and believe its growing military engagement in the Pacific betrays a long-term objective to establish a naval base there — an unthinkable outcome for Australia.

Others say China’s financial aid is essentially “debt-trap diplomacy”, with unsustainable loans providing a pathway for China to control the strategic assets of Pacific states.

The Lowy Institute has shown that China has not been a major driver behind rising debt in the Pacific, but it nevertheless has a responsibility to help prevent future debt risks. The scale of its lending patterns — and the absence of mechanisms to protect recipients from debt — present substantial hazards for some countries.

There’s been no sign yet that Beijing is prepared to collaborate with western donors as they engage with regional countries to mitigate these risks. This would signal China cares about the region’s sustainability — an important qualification for a genuine partner.

Chinese representatives sometimes struggle to understand that centralised control is not the Pacific way. In the commercial sphere, effective partnerships require patient management of multiple stakeholder relationships — with landowners, local authorities and environmentalists.

In Papua New Guinea, however, Chinese firms like Shenzen Energy and Ramu Nickel have been disappointed that agreements they have signed with the country’s prime minister haven’t guaranteed smooth project implementation.

China also showed great frustration in the Solomon Islands when provincial leaders thanked Taiwan for coronavirus-related aid, which was delivered after the national government had switched diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing.

Success also requires conscious support for national development aspirations and a willingness to lean in at difficult moments.

Australia and New Zealand don’t always escape criticism from the region; climate change and labour market access continue to be sore points.

But over time, these traditional partners have shown their commitment to the region’s development through the investment of billions of dollars. They have helped run elections, repeatedly deliver disaster relief and mount stabilisation missions in regional hot spots.

This kind of comprehensive partnership, recently reaffirmed in a new economic and strategic development agreement signed between Australia and PNG, is outside Beijing’s traditional comfort zone.

The current pandemic poses very serious risks to the fragile economies of the Pacific. It’s an important moment for regional partners to show their commitment.

Beijing has highlighted its Pacific Conference on COVID-19, a video link-up in May between the Chinese vice foreign minister and senior Pacific representatives, as a sign of its support for the region.

But there were no substantive outcomes, and despite multiple press releases, China appears to have announced only A$3.5 million in virus-related regional support.

This contribution by the world’s second-largest economy is about half what one Australian mid-sized company has committed in COVID-19 support to PNG alone.

It also pales in comparison to the A$100 million that Australia announced in March would be redirected from existing aid programs to mitigate the regional effects of the virus.

Australia has also stepped up in other practical ways, for instance, by processing some coronvirus tests from the Pacific, sending rapid diagnostic testing equipment to the region and deploying Australian Medical Assistance Teams to support PNG’s response to rising cases there.

And perhaps most notably, Australia announced recently it will deliver a future coronavirus vaccine to the people of the Pacific, once it’s approved.

China might actually have some things to offer the region, including lessons from its highly successful development model.

But it will need to be more thoughtful about the region’s actual needs and aspirations if it wants to build a substantial and effective partnership with the Pacific in the wake of this pandemic.

Ian Kemish, Former Ambassador and Adjunct Professor, School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.