As the climate changes, southern Australia is likely to keep getting drier on average, particularly in the southwest.

However, this year has been wet. And yesterday the Bureau of Meteorology announced we are now in another La Niña event. This common large-scale climate pattern lasts for months, and will increase the odds of further wet weather across the country.

So despite the long-term trend towards drier conditions, we find ourselves in a wetter-than-usual period. What gives?

Current climate change assessments

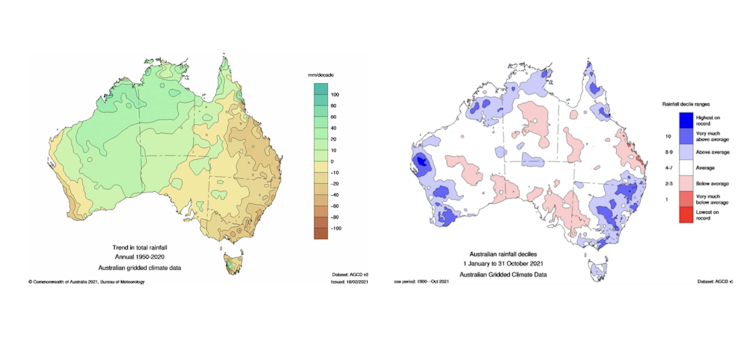

Rainfall has been declining in much of southern Australia in recent decades (see below). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment report – which draws on the latest climate research – found the recent drying trend in southern Australia is likely to continue, particularly during the cool season.

Cool-season rainfall in southwest Western Australia has already decreased, and ongoing drying in this area is assessed to be very likely. There’s strong evidence this trend contains a “signal” of climate change, otherwise known as a climate change “fingerprint”.

We understand the drying has been driven by changes in dominant weather patterns. And future projections of drying in the southwest are among the strongest in the world.

The situation in the southeast of Australia is not as clear, but there’s strong evidence for an ongoing decrease in rainfall here, too.

Yet, we find it has been wet in many southwest and southeast regions this year – including in the cool season. In fact, some areas received “very much above average” rainfall in the ten months to the end of October, seemingly defying the drying trend.

Variability is king in Australia

Australia has always been the land of droughts and flooding rains. It’s normal to be beset by a multi-year drought, before experiencing major floods. Year-to-year variability here is large compared with most of the world’s other land regions.

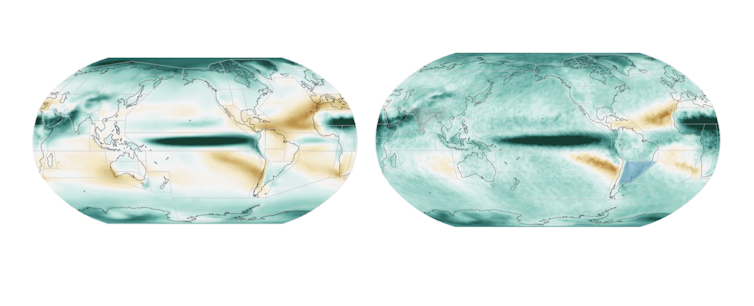

In 2021, we’ve seen a wet swing of the climate needle due to several global climate drivers. Alongside the Pacific now being in the La Niña phase, the Indian Ocean Dipole is in a negative phase.

When we see these drivers line up, we know the deck is stacked for a wetter season. This is what we’ve always found, and we can count on Australia’s climate variability to remain, through this century and beyond.

So does a wet year cast doubt on our assessment of climate change? No.

In the 2020 State of the Climate report, released by the CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology, we noted recent rainfall trends are tracking within projections.

In fact, we showed rainfall trends since the baseline of 1986-2005 to 2020 are tracking in the dry end of projections for the southwest and Victoria. This suggests that if anything, the projections are likely conservative.

Of course there are wet years, such as this year and also Victoria in 2010. But the longer-term trend has been downward. This is consistent with what we expect from climate change, after drawing on multiple lines of evidence and climate modelling.

2021 is not extraordinary in the long-term context. Even if the whole of 2021 ends up being very wet, it won’t shift the long-term trend by much. Only a persistent wet trend over decades or longer would raise questions about our assessment of climate change and current projections.

What does a ‘drier’ climate look like?

As the global climate warms, global average rainfall is increasing – and we expect most regions of the world will actually become wetter.

But there are some regions which will get drier, including southern Australia, the Mediterranean and southern Africa. So what will this look like?

A trend towards a drier climate will come with a lot of ups and downs. For example, between 1900 and 2020 southwest Western Australia’s annual rainfall varied between about 393mm and 1035mm (-40% and +55% from the average). This is a huge range.

Climate projections suggest a persistent rainfall reduction of up to 15% in the southwest of Australia is plausible over the first part of this century. Change later in the century will depend on whether we limit further climate warming.

If we do limit it, we can expect the rainfall to decrease by up to 20%. If we don’t, it will decrease by up to 35% – with larger reductions very plausible in the cool season. In either case, these projected average changes are still smaller than the year-to-year variability recorded in Australia over many decades.

But this doesn’t mean the trends and projections aren’t important. A persistent and ongoing shifting towards drier conditions, with drier (and hotter) dry spells is a huge challenge for Australia’s water managers and primary producers. And with a lower rainfall average, the chances of unprecedented dry periods are higher.

Wet extremes expected

But not every year will be a drought. There will still be wet days, months and years.

In fact, wet extremes are likely to increase despite the drying trend. Even in regions where the average rainfall is expected to decrease, there is a projected increase in intense rainfall bursts and rainfall extremes.

This includes intense hourly rainfalls that can lead to flash floods, as well as major rainfalls from “atmospheric rivers”, which are strong channels of concentrated moisture that stream through the atmosphere above us, delivering water for extreme rainfalls.

So for parts of southern Australia, a likely outcome is lower rainfall on average, but an increase in extreme rainfall events. With lower water availability overall, punctuated by intense flood risk, we can anticipate significant challenges ahead.

Michael Grose, Climate projections scientist, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.