Sean H Vanatta, University of Glasgow

There has been much talk about a potential inflation surge as countries lift pandemic restrictions and seek to resume normal economic activity. In recent months, US prices have risen more than 5% year-on-year. In the UK, price growth has been slower and was even slightly below expectations for July, but is likely to accelerate again.

This situation closely resembles what happened after the second world war. Then as now, governments were confronted with consumers eager to spend and industry not yet ready to meet consumer demand. Whereas in 2021 firms and their supply chains are struggling to meet unpredictable demand amid COVID restrictions, in 1945 producers needed time to return to business as usual after years of manufacturing for the war.

With inflation looming, officials had the courage to impose bold controls on consumer credit to curb demand. This might seem unthinkable in today’s climate, but there are good reasons for doing this again.

What happened after the war

The US and UK actually introduced controls during the war, both to curtail inflationary, credit-fuelled demand and to redirect financial resources towards national defence. US President Franklin Roosevelt summarised the policy crisply in 1942:

We must discourage credit and instalment-buying [hire purchase], and encourage the paying off of debts, mortgages and other obligations; for this promotes savings, retards excessive buying and adds to the amount available to the creditors for the purchase of war bonds.

The Federal Reserve duly introduced restrictions on lenders. For hire purchase, which commonly financed cars and household appliances, consumers were required to pay 33% of the price upfront and repay the rest over 12 months. The government also restricted retail credit accounts, requiring them to be repaid in 90 days.

The UK introduced similar controls, limiting credit for hire-purchase of goods that required expensive foreign metal imports. This shrank hire-purchase credit to 10% of its prewar total.

After the war, the US and UK maintained these controls to restrain demand for goods at a time when they remained in limited supply. The controls were also about moderating the peaks and troughs of the business cycle. Officials believed that consumer credit had driven growth and inflation during previous upswings, but deepened the fall when consumers stopped spending their earnings and didn’t or couldn’t borrow. This, it was believed, had prolonged the great depression.

The ensuing decades

The US lifted its controls first. The government had struggled to enforce the rules during the war and subsequently faced a business backlash against government power, including objections to credit controls. As one bankers’ group explained to congress in 1947: “Regulation of consumer credit by federal authority is unnecessary, ineffective, un-American, unsocial, inconsistent, and impractical.”

The US controls expired in 1949, were briefly revived for the Korean war in 1950-53, but extinguished thereafter. Nevertheless, controls remained part of the political debate. As late as 1980, President Jimmy Carter briefly reimposed them to combat inflation.

Controls remained more consistently in place in the UK, where the fight against inflation blended with efforts to defend the pound. Besides maintaining hire-purchase restrictions, the government later capped the amount citizens could spend on credit cards abroad. There was also an ill-fated “credit corset”, which required banks to make special deposits at the Bank of England against new loans in the 1970s. Both Conservative and Labour governments continued experimenting with credit controls until 1982.

On the continent, postwar governments favoured more direct economic management, but this could lead to similar policies. In France, for example, the National Credit Council imposed consumer controls in 1948 and maintained them until 1979, occasionally requiring down payments as high as 50%.

In all these countries, credit controls restrained consumer borrowing and helped control inflation during the 1940s and beyond. They also ensured that wage growth, rather than consumer borrowing, would drive postwar prosperity.

The modern era

In the early 1980s, deregulation-mania swept away these controls as the new economic liberalism adopted by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher took centre stage. Credit controls were viewed as undesirable state intervention, and arguably remain taboo today.

Besides ideology, governments will be reluctant to consider controls when they are desperate for a consumer spending boom. Like the postwar era, many consumers are sitting on large cash reserves from saving much more than usual during the pandemic.

Although they curtailed credit spending earlier in the pandemic, paying off balances instead of incurring new ones, credit spending has since accelerated. Consumer borrowing has been the motor of economic growth in recent years and will be seen as vital to achieving a recovery from the worst downturn in living memory.

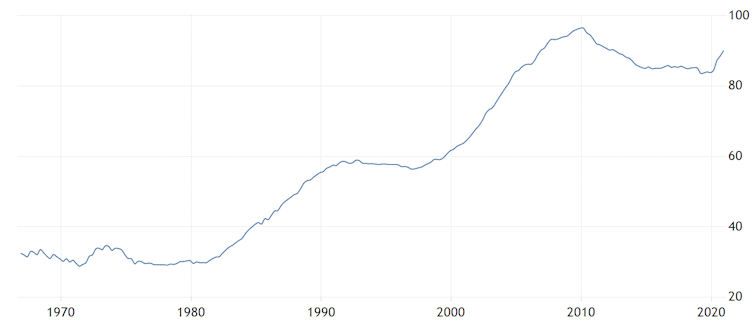

Consumer debt as a % of GDP

Yet the long-term arguments in favour of controls bear re-hearing. Credit drives growth, but also instability in the form of booms and busts, and inequality, because consumers spend instead of saving – thus making it harder for people to build wealth. And while credit increases people’s buying power, when supplies are curtailed, it also causes inflation.

The pandemic, like war, offers a unique moment to reconsider our debt-dependent economy. Workers, empowered by the current labour shortages, are demanding higher wages. Wages, not debt, are the appropriate foundation of consumer purchasing power.

Governments may have an easier time implementing and supervising credit controls in the digital era. Controls may also prove useful in addressing new goals, including combating climate change by limiting credit for carbon-intensive products (and generally by restraining consumer capitalism’s most wasteful impulses).

Finally, many of the poorest in society use excessive borrowing to survive. Governments found ways to protect the most vulnerable in the depths of the pandemic. They could continue to do so, rather than depending on exploitative private credit.

As US consumers ramped up borrowing after controls expired in the mid-1950s, the economist John Kenneth Galbraith asked: “Can the bill collector or the bankruptcy lawyer be the central figure in the good society?” We should ask that question again.

Sean H Vanatta, Lecturer in US Economic and Social History, University of Glasgow

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.