Patrcia Ranald, University of Sydney

They and other companies have successfully lobbied for rules in the CPTPP and other bilateral and regional agreements that give them rights to bypass courts including Australia’s High Court and sue governments in extraterritorial tribunals for income they claim restrictions have cost them, using so-called Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) procedures.

Such provisions do not exist in the rules of the World Trade Organisation itself, which is the body formally charged with regulating global trade.

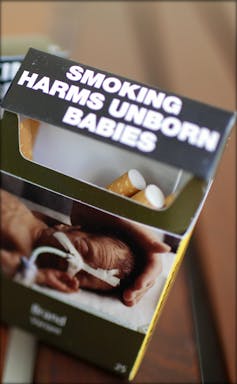

The Philip Morris tobacco company used such rules in a Hong Kong-Australia agreement to claim billions of dollars in compensation from Australian for plain packaging legislation.

Defeating this claim took Australia seven years and A$12 million in legal costs.

There have been increasing numbers of such cases against governments regulating to reduce carbon emissions and combat climate change.

An international arbitration law firm Aceris Law LLC has told its clients

while the future remains uncertain, the response to the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to violate various protections provided in bilateral investment treaties and may bring rise to claims in the future by foreign investors

An Australian law firm Alston & Bird is advertising an event called “The coming wave of COVID-19 arbitration – looking ahead”.

Legal scholars critical of ISDS say governments could face an avalanche of ISDS cases after the pandemic is over.

ISDS clauses establish rights to sue

Foreign investors could allege that governments are breaching the “direct expropriation” clauses of ISDS rules by appropriating private health and other assets for public use.

Lock down rules that affect profits could be interpreted as “indirect expropriation”.

The pandemic is also raising questions about other aspects of Australia’s trade agreements.

Despite pleas from the Productivity Commission, each is negotiated in secret without an independent evaluation of its costs and benefits.

Often the agreements open up essential services including health, to private foreign investment, with only limited carve outs to allow regulation which can be wound back, but not widened, over time.

They have also allowed pharmaceutical companies to increase their 20-year monopoly on new medicines, delaying the availability of cheaper medicines.

In the past month the realities of the pandemic have forced the Australian government to (at least temporarily) back away from this approach.

It has directed private hospitals to treat pandemic patients.

It has assisted local firms to reestablish the capacity to manufacture equipment such as facemasks.

And it has ramped up screening of foreign investment by the Foreign Investment Review Board, in a way trade agreements would normally prevent.

Post-pandemic trade policies should reject both the extremes of recent agreements and the Trump and Hanson policies of building walls and a return to high tariffs.

Post-pandemic, we should wind such clauses back

Australia should also reject the trap of taking sides in the US-China trade wars.

Trade agreements should be negotiated openly in a system that takes account of the specific needs of developing countries.

They should reinforce internationally-agreed and fully-enforceable labour rights and environmental standards, allow countries such as Australia to maintain the manufacturing capacity that will be needed in the event of crises and enable governments to regulate for purposes of public health and the environment.

They most certainly should not strengthen medicine or other monopolies, or give additional legal rights such as ISDS to global corporations that already have enormous market power.

Patrcia Ranald, Honorary Research fellow, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.