Mehdi Shiva, University of Oxford

In Afghanistan, about 11 million people – 35% of the population – are struggling to get access to decent food. The years of conflict have played a part, and a bad harvest has helped to drive up food prices, but much of the problem relates to the COVID-19 pandemic and the containment measures introduced to deal with it. Nearly 4 million people are one step away from famine.

Afghanistan reported its first COVID-19 case in February 2020. The government brought in containment measures, introduced screening at border crossings, quarantined infected people and banned public gatherings. It imposed a countrywide lockdown the following month, including closing workplaces, and subsequently extended it twice. In other words, it responded similarly to many wealthier countries. Yet the results have been noticeably more painful.

Border closures, panic buying and disrupted planting all contributed to severe food shortages and the rise in prices. Together with job losses and reduced household income as restrictions weakened the economy and hampered trade, it pushed thousands of Afghan families into poverty. This threatens to reverse social development gains made over the past decade, such as reduced infant mortality.

I recently co-authored a study into how COVID responses affected different countries. Our findings question whether low-income countries were right to restrict economic activity to the same extent as more developed ones. In future, they might be better pursuing COVID policies that save as many lives but have lower economic costs.

Containment contrasts

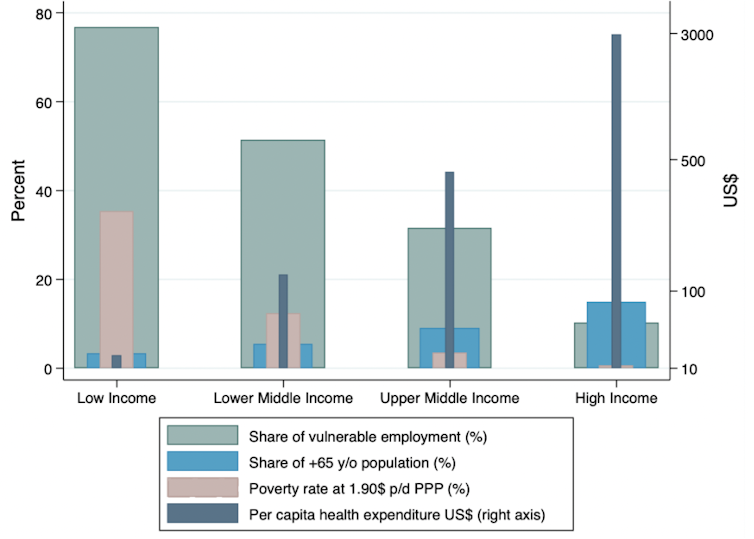

Containment has lowered COVID-19 fatality rates significantly across the globe. It has slowed transmission, giving national health services time to prepare for people with serious symptoms, while still being able to care for non-COVID patients. However, these benefits vary by a country’s income level. By our calculations, similar measures were almost twice as effective at cutting deaths in rich countries than poor ones. There are similar findings from another study about the effect of containment on infection rates.

One reason for this variation is that hospitals in poorer countries were already overstretched before COVID, and their ability to increase the provision of healthcare was limited. For example, a World Health Organization survey of 47 African countries in May 2020 revealed on average nine intensive care unit beds per 1 million people, compared with about 2,000 to 11,000 per 1 million in EU countries.

Social distancing has also been difficult in many poor countries because they don’t have the resources to enforce such restrictions. And most people need to go out of their house for basic needs, pandemic or not. For example, 90% of people in Afghanistan do not enjoy simultaneous access to electricity, clean water and good sanitation.

Workplace closures

When it comes to shutting workplaces, our results are particularly interesting. We used econometric modelling to compare the effects in different countries of workplace closures that were full, partial and recommended as opposed to mandatory.

In high-income and middle-income countries, full closures were associated with the highest reduction in fatalities (we did not weigh the economic costs and benefits). This was in line with academic predictions published at the beginning of the pandemic. On the other hand, full workplace closures in low-income countries were no more effective at reducing COVID fatalities than the alternatives that we considered. Why would this be?

Again, lack of resources such as policing has made it hard for these countries to enforce the rules. Blanket workplace closures also assume that households can tolerate the economic and psychological pressures that quickly arise, but many in developing countries cannot. Workers prevented from working have not been cushioned by unemployment benefits, government furlough schemes or cash grants for food.

Weaker healthcare is also part of the equation. Clearing the streets by using workplace closures – albeit with only partial success – may reduce the spread of the virus. But it will convert less well into fewer fatalities unless the health system can treat people effectively.

You therefore have a policy that is undermined from within by a combination of poor enforcement and a strong incentive for workers to ignore the rules, and from the outside by a health system that is too weak to make the most of any benefits. Yet as the case of Afghanistan suggests, low-income countries are still likely to pay a hefty economic price for workplace closures even if they are not particularly successful.

The targeted approach

So what could developing countries do instead of full workplace closures? Many development specialists make a compelling case for using a more targeted approach to closing workplaces. This would involve tailoring measures for local conditions rather than blindly emulating the full closures in high-income countries.

For example, a study from 2020 suggested that instead of a comprehensive lockdown in India, a better strategy might have been to allow young adults to work while older members of households were insulated and cared for by their families. This would have reduced the economic damage from lockdown while still protecting those who needed it the most.

Another targeted approach might be to close only labour-intensive workplaces, potentially imposing a temporary tax on workplaces that stay open to help compensate workers subject to closures. Such options would be worth considering in India right now.

Clearly, mass vaccination roll-outs in low-income nations are also an essential part of the answer. We have seen a huge disparity so far, with wealthy countries vaccinating one person every second while the majority of the poorest nations are yet to give a single dose. As things stand, most poor nations will not achieve mass COVID immunisation before 2024. Unless this is brought forward, a smarter approach to shutting down economies will not be able to deliver results.

Mehdi Shiva, Economist, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Explore top-rated compensation lawyers in Brisbane! Offering expert legal help for your claim. Your victory is our priority!

Explore top-rated compensation lawyers in Brisbane! Offering expert legal help for your claim. Your victory is our priority!

"

"