Amy Clair, University of Essex

COVID-19 has been described as a “housing disease”. Overcrowded living conditions make it easier for the virus to spread, and statistics show a link between overcrowding and mortality from COVID.

In my new research published in the International Journal of Housing Policy, I found that reductions to housing benefits led to a significant increase in overcrowding among private renters in England in the years leading up to the pandemic. My analysis shows that more than 75,000 additional households were overcrowded during the pandemic because of these policies.

Changes to housing benefit

The local housing allowance (LHA) approach to calculating housing benefit for private renters was introduced by the Labour government in 2008. Previously, housing benefit was based on the actual rent paid by individual recipients. Arguing that this was undermining work incentives, the LHA approach instead meant recipient households could receive support up to the median rental prices for the relevant property size in their area. The median, or 50th percentile, represents the “middle” value between the lowest and highest values – in this case the lowest and highest rents, therefore making the cheapest half of housing in an area affordable to recipients.

After the 2010 election, the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government made further changes with the aim of reducing spending. From April 2011, LHA rates were reduced from the 50th to the 30th percentile, meaning that housing benefit would now only cover rents for the cheapest three out of 10 homes in an area. This resulted in an average loss of £1,220 per household per year. Caps depending on property size were also introduced.

The government argued that the lower levels of support would encourage lower rent levels. However, a government-commissioned review found that this was not the case: the vast majority (89%) of the effects fell on tenants who had to find money for their housing costs elsewhere, while just 11% of the effects fell on landlords via reducing rents.

In the years that followed this change, the way that LHA rates were updated to keep up with rising rents was also altered. Previously increased monthly according to rental prices, from April 2013 increases took place annually, capped at the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation. The Consumer Price Index calculates inflation based on the price of a range of goods and services, but does not include housing costs.

Annual increases were further restricted to 1% in 2014 and 2015 before being frozen for four years. This led to a widening gap between LHA rates and rents in the years leading up to the pandemic. For example, in the year to 2016 while increases were limited to just 1%, actual rents in England increased by 2.5%.

Overcrowding

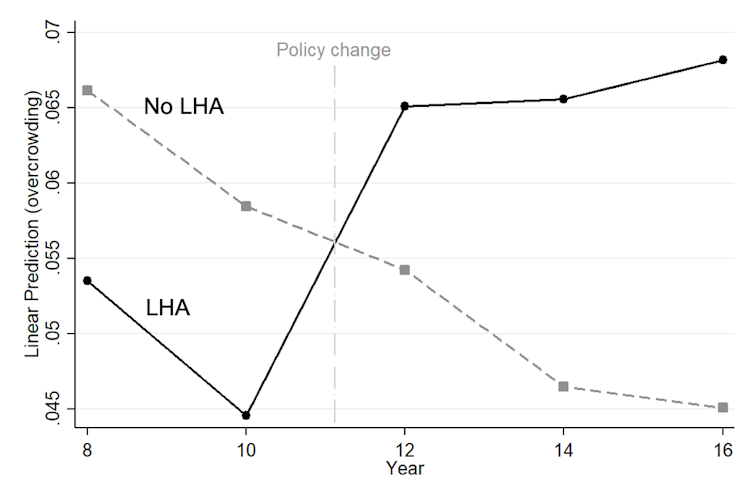

One potential way for renters to adapt to lower financial support is to move into smaller and less suitable homes. In my research, I compared trends in overcrowding both before and after the LHA reductions, as well as between private renters who do and do not receive support. By using this approach, I found a causal link between the policy changes and overcrowding.

My analysis first looked at the immediate effect of the cut to LHA rates from the 50th to 30th percentile of rents in an area, finding an increase in overcrowding of over 5% in England. This is equivalent to 75,000 additional households living in overcrowded homes.

I then looked at the longer-term effect of the changes, including the changes to to the way LHA rates were set, which undermined the link between allowances and actual rents. The results show further increases in overcrowding for recipients of housing benefit, while overcrowding for other private renters continued to decrease.

Spread within households has been one of the main routes of COVID-19 transmission, putting people in overcrowded homes at greater risk. Overcrowding makes self-isolation and reducing risk much harder and less pleasant, and is associated with poorer mental and physical health.

During the pandemic the government did increase the LHA levels back to the true 30th percentile of rents, reversing the effects of limits to increases. But failure to adjust the benefit cap in response will have significantly reduced any beneficial effect this may have had. Between February and May 2020 there was a near doubling of households who had their benefit income reduced by the cap, disproportionately affecting single-parent households. LHA rates have once again been frozen.

Moving forward

These findings support calls from housing organisations such as Shelter to increase the LHA back to the 50th percentile, and to once again increase allowances in line with rents. This would protect private renters from financial hardship in the short term while a more sustainable housing policy should be the longer-term goal. While this conflicts with government’s approach of once again freezing LHA rates and reducing spending, three arguments against such an approach should be considered.

Firstly, the increased spending on renter support reflects government decisions more than it does excessive or frivolous spending by benefit recipients. Continuous reductions in support for the social rented sector have led to more people living in the private sector, where rents, and therefore housing benefit rates, are higher.

Secondly, many policies to “improve” access to home ownership have, at great cost, inflated housing prices and made accessing ownership more difficult for renters. These policies benefit large housebuilders, and those already in owner occupation. Given these impacts, support for renters should perhaps not be the main target of actions to reduce housing spending.

Finally, reducing LHA levels may have reduced government spending on housing, but its consequences will have led to increases in spending elsewhere, particularly health. A person’s home is central to their broader health and wellbeing – in an era where low housing quality has been directly linked to the spread of a deadly disease, housing policy must take this into account.

Amy Clair, Research Fellow in Social Policy, University of Essex

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.