Arturo Bris, International Institute for Management Development (IMD)

Danone’s chief executive and chairman, Emmanuel Faber, is to step down after activist shareholders called for his removal. In particular Artisan Partners and Bluebell Capital Partners, which together own less than 6% of the Paris-based food giant, explicit requested the board find a replacement.

They blame Faber for “a combination of poor operational record and questionable capital allocation choices”. Bluebell said that Faber’s Danone “did not manage to strike the right balance between shareholder value creation and sustainability”.

It was well known that for the chief executive of Danone, whose brands include Actimel, Alpro and Evian, the goal was to balance purpose with profit. “Stakeholder Capitalism is a Fact” was the title of a Fortune Magazine article published about him in July 2020. This was encapsulated in Danone’s logo, with a child looking up at a star next to the strapline, “One Planet. One Health”.

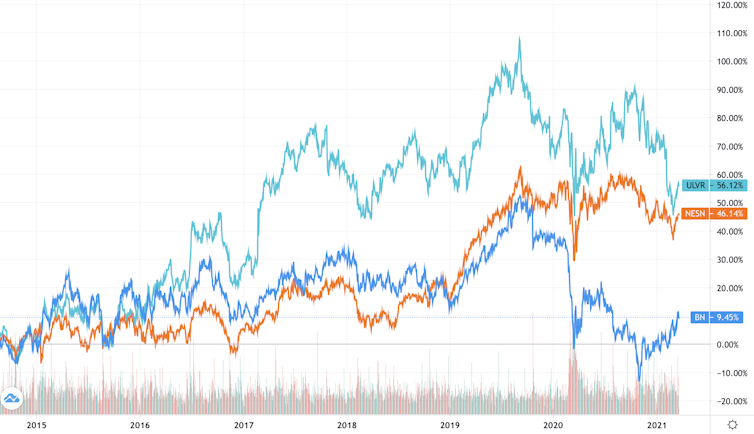

Unfortunately Danone’s share performance has been very weal compared to rivals Nestlé and Unilever. Danone is perceived to have cared more about people, the planet and social responsibility than its shareholders, and Faber is paying the price. If we measure a strategy’s success by the extent to which the shareholders accept it, “One Planet. One Health” has been a failure.

To many it seems unfair that old-fashioned capitalism, targeting short-term gains, has been defeated here by the idea of a new form of stakeholder capitalism in which companies pursue the interests of employees, society and future generations, at the expense of investors. They are partly right but partly wrong, and even insofar as they are right they are blaming the wrong people. Let me explain.

Shareholders and the long term

Doing what shareholders want is not incompatible with other stakeholders – rather, the opposite. Long-term shareholders are more long-termist than any other stakeholders in an organisation. Customers can take their business elsewhere; employees can change jobs when they do not share the company’s values.

Yes, there are so-called “short-term” shareholders. But they are not the majority of pension funds and mutual funds who hold most publicly traded shares and want to preserve the long-term value of a company.

Even institutions focused on short-term gains require stupid investors on the other side. If Artisan wants to hold Danone’s stock for just months, it will have to sell to someone. And if the stock has been inflated via a short-termist strategy, who will buy it?

Food giants’ share performance

It is worth reflecting on Nestlé here. In July 2018, activist shareholder Daniel Loeb from US investor Third Point Management sent an angry letter to Nestlé’s chief executive, Mark Schneider, following a similarly dismal share performance.

Schneider, a newcomer to the largest consumer goods company in the world, had implemented a strategy based on diversifying away from Nestlé’s traditional business of coffee and chocolate into health science. Third Point wanted Nestlé to sell off certain businesses, while arguing that it should take on more debt to take advantage of low interest rates.

Schneider complied with this supposedly short-termist plan, and the share price has risen 32% since July 2018. In contrast, Danone is down 2% over the period, while Unilever has only gone up 3%. Today everybody at Nestlé, including customers and employees, is extremely happy with the changes imposed by Third Point. Seen in this light, perhaps we should be congratulating Danone’s activist shareholders.

Sustainability

If you want to do more for other stakeholders, such as future generations, the underlying problem is the rules of governance. They stipulate that shareholders’ interests must be given top priority by company directors. I remember an executive summit in Copenhagen a couple of years ago where the chief executive of a top European company, replying to concerns about the firm’s environmental policy, candidly said that if he made it greener, “my profit margin would fall 3% per year, my stock price would fall 15%, and I would get fired”.

Stakeholder capitalism ultimately needs enforced by politicians, and politicians are chosen by people. If western democracies are mostly run by political parties fostering traditional capitalism, it is our fault – it is because most people do not want to be sustainable.

Danone is not the last company whose shareholders are going to rebel when the company does not create value for them. If we want a new form of capitalism, but expect executives to change the system without politicians changing national and international regulation, we have two choices.

The first is that companies cater to different shareholders: if you want to have a higher purpose than profit, appeal to investors who are willing to lose money to preserve society and the environment.

Incidentally, don’t kid yourself that you can rely instead on investment giants like Blackrock who run index funds that exclude companies that don’t meet criteria around sustainability, while claiming that stakeholder capitalists will be the winners of the future.

These institutions manage other people’s money, and transfer the burden of sustainability to the ultimate holders of the shares. Shareholders in the new capitalism will be those willing to sacrifice personal financial gains for a social benefit. Are you one of them?

The second choice is to rely on innovative executives to come up with new business models that find a way to generate shareholder returns while being sustainable. This is not easy. Most business models that I see either impose the cost of sustainability on shareholders by achieving lower returns, or on suppliers by paying them less, or on customers in the form of higher prices.

Only a few create truly sustainable business models. For example Vestergaard, a Swiss-headquartered company, patented a product to provide clean water to rural populations in Africa which was financed by selling carbon credits. In such a model customers, users, suppliers, owners and government authorities won. A chief executive running a business like that should be safe from being removed for caring too much about sustainability.

Arturo Bris, Professor of Finance, International Institute for Management Development (IMD)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.