This piece is republished with permission from Commonwealth Now, the 59th edition of Griffith Review.

Anyone interested in power must visit Persepolis. Its ruins stand defiantly in a parched valley in southern Iran, the ultimate statement of humans’ capacity to dominate vast multitudes of their fellow humans.

Amid the intricately carved stairways, walls and plinths stand the two halls from which the Achaemenid Empire radiated its power, from the Indus to the Danube. The Apadana, begun by Darius in 518 BC and finished by Xerxes, was where the King of Kings received tribute from the variety of peoples he ruled.

With walls 60 metres long, its huge ceiling of Lebanese cedar was supported on 72 columns of carved grey marble, each 19 metres high. Next to the Apadana is the even larger Throne Hall, its massive roof once supported by 100 columns, each of its eight carved stone doorways depicting the King of Kings wrestling with a mythical monster.

The architecture of these two halls, and the stairways leading to them, was designed to inspire awe in the subjects of the Achaemenids. Any tributary hoping to see the King of Kings would be so disoriented by the time he saw the throne as to be utterly prostrate at the heart of the largest empire the world had ever seen.

Also see: The ties that (still) bind: the enduring tendrils of the British Empire

The British Empire has no Persepolis. Its beginning and end weren’t marked by the construction and destruction of a city. London began as an outpost of another empire, and has continued to flourish long after the fall of its own.

Neither is there a founding date or a battle in which Britain decisively beat its predecessor and was universally hailed as the new world power – just as there is no decisive defeat that marks its end.

The British Empire is a story of ambitious, evangelical, avaricious but ordinary men and women, and a weary, reluctant Whitehall bureaucracy dragged toward formalising what its citizens had created on the frontiers of enterprise in Asia, Africa and the Pacific.

Far from popular notions of an empire driven by surging jingoistic ambition, British society was deeply divided about the benefits and morality of empire at the time of its greatest expansion.

By the mid-19th century, a rising tide of opinion opposed to imperialism on material and moral grounds had begun to contest the pro-imperialist dominance of the Tories under Palmerston and Disraeli. Britain’s economy had started to sputter and lose ground to surging industrial rivals; accumulated war debt and rising taxes were generating popular resentment.

William Ewart Gladstone, at the head of a surging Liberal movement, combined moral attacks on the Tories’ overseas adventurism with a hip-pocket campaign that debt and taxes were the direct consequence of imperial ambition.

And yet, the 70 years that followed 1850 saw the fastest expansion of the empire in history. Hundreds of millions of Asians, Africans, Pacific Islanders and Americans found themselves ruled by Britannia. Apart from in India, the British preferred to govern through local systems of government – and, more often than not, reluctantly.

As the French and the Germans became determined to build themselves global empires, the British were forced to clarify their intentions in vast areas of the world where they had simply asserted a sphere of influence by virtue of the British navy and British commercial dominance.

Repeatedly, where they had been prepared to stand aside in a bid to manage complex relations with their continental rivals, the British found their hand forced by the thrusting subjects in their dominions, who had none of the Empire-weariness of British society.

After the first world war, a bloodied and impoverished Britain found itself forced to take on yet more territory surrendered by vanquished empires in the Middle East and Africa.

Just as the British Empire has no founding moment, neither has it an emphatic final act. There is no burning of Persepolis from which history will forever date the demise of Rule Britannia. After the second world war, the largest empire the world has ever seen declined exactly as it had arisen – through the self-interested acts of thousands of subjects, overseen by an overwhelmed Whitehall bureaucracy, amid an ambivalent British public, romantic and cynical at the same time.

Even today, Britain can’t divest itself of territories that cause it diplomatic difficulties – the Falklands, Gibraltar, Northern Ireland – thanks to the attachment of their populations to membership of a vanished empire.

And while the British Empire’s gracious decline can be seen as a tribute to the prim pragmatism of the same national character that built it, the lack of a final act may carry an ominous thread. Without a clear full stop there can be no certainty that the unravelling has ended even now.

The evolution of the Commonwealth

The key to Britannia’s reluctant rise and dignified eclipse lies in a mystical association: the Commonwealth.

The displacement of “empire” by “Commonwealth” first happened amid the horror of the first world war, at the Imperial War Conference of 1917. Britain, its self-governing dominions – Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Newfoundland – and India had come together to discuss the form and function of the empire after the war.

Britain had come to rely ever more heavily on the Empire for its survival during the cataclysm. In full knowledge of this, the dominions and India had begun to demand a greater say over an imperial foreign policy that could have such momentous consequences for them.

The Imperial War Conference issued Resolution IX, which recognised:

… the dominions as autonomous nations of an Imperial Commonwealth, and … India as an important portion of the same.

The resolution further recognised:

… the right of the dominions and India to an adequate voice in foreign policy and in foreign relations, and should provide effective arrangements for continuous consultation in all important matters of common imperial concern, and for such necessary concerted action, founded on consultation, as the several governments may determine.

Names matter. In naming something or someone, not only do we give them a social handle, we also aim to define the essence of what they are and what we want them to be. Names are meant to shape their hosts and evoke behaviours; that’s why we remain so fascinated by what particular names “mean”. “Commonwealth” was chosen by a succession of statesmen for no less a reason.

Let’s start with the noun it replaced. The British, as they became increasingly devoted to liberal politics and economics, the rule of law and freedom of religion, had grown increasingly uncomfortable with the idea of empire. These were what despots and autocrats built; Britain’s growing dominion was something entirely different.

Like ancient Athens, they told themselves, Britain’s was a liberal empire: built on democracy, free trade and maritime strength, not on huge standing armies and command-and-control repression.

Queen Victoria may have been named “Empress of India”, but Britons could not bear to think they were in charge of a project akin to that which Louis XIV, Frederick the Great or Napoleon had tried to build.

And so they found a gentler, less precise title. But “Commonwealth” was not without controversy, evoking for some the horrors of Cromwell’s own very English revolutionary fervour and despotism.

The rehabilitation of “Commonwealth” was simultaneously occurring in Australia, at a time when the colonists were contemplating their own momentous remaking of their political order. As historian W.K. Hancock pointed out, the name was adopted:

… as a manifesto, a declaration of faith in a way of life, rather than as an accurate descriptor in terms known to political science. The name Commonwealth is a programme in itself.

“Commonwealth” is an anglicisation of the Latin term res publica: “the welfare of the people”. But the modern usage of this term – “republic” – carries with it a precise constitutional framework, as defined by the jurists of the Roman Republic and the constitutional fathers of the US.

“Commonwealth” is less precise, more mystical. It dates from the late 15th century, when England was throwing off the yoke of the Roman church and abolishing feudalism. At a time of great political, social and ecclesiastical upheaval, the English coined a term evoking a comforting vision of an idealised Anglo-Saxon harmony.

For Hancock:

The idea depended on the conception of society as a mystical body, as an organic unity based on a just and harmonious distribution of functions and rewards among the various degrees and estates of men … The idea of the Commonwealth as a mystical body denied that any man or any rank possessed a natural right to power and wealth: it insisted on stewardship.

How perfect for an empire acquired by anti-imperialists. Theirs was not a system of domination and extraction, they told themselves – it was a voluntary association of free societies, held together by sentiment and loyalty for the mutual support and welfare of all.

Surely it is a testament to the power of names that the Commonwealth gained in strength and sentiment even as the empire it tried to deny became ever more repressive, extractive and attached to racial hierarchy.

As the great Commonwealth loyalist Alfred Deakin wrote in London’s Morning Post in 1906, the British Empire:

… though united in the whole, is, nevertheless, divided broadly into two parts, one occupied wholly or mainly by a white ruling race, the other principally occupied by coloured races who are ruled. Australia and New Zealand are determined to keep their place in the first class.

The Commonwealth thus became a cypher for the arc of British imperial delusion. Its siren call of volunteerism and the good-of-all convinced a nation caught in industrial eclipse to expand its responsibilities vastly beyond what it could ever hope to maintain.

And, repeatedly, it maintained association among the disparate parts of empire when rational statecraft would have brought an emphatic end to the quixotic enterprise.

By the 1870s, Britain was under serious threat from the rising powers of France and Germany in Europe.

With industrial, military and scientific eclipse beckoning, the empire needed to become a state, refocusing its energies on dominating the near seas and ensuring the balance of power in Europe. Instead, its energies were dissipated at the edges of empire. Where it should have been concentrating its power in Europe, Britain suffered humiliating defeats at the hands of the Afghans in 1878 and the Zulus in 1879.

So it was for the dominions. By the early 20th century, Australia and New Zealand were rightly preoccupied by competition from rising powers in the Pacific.

Never was there a greater need to manage relations and build their own defences and military capabilities. Yet they remained tied to the foreign policy of empire, even as the empire entered an alliance with Japan, the country that most worried them, and then granted it the right to retain the Carolines and Marshall Islands in the Central Pacific after the first world war.

At the Washington Naval Conference of 1921, dedicated to finding a solution to the rising rivalry in the Pacific, the antipodean dominions chose meekly to be represented by the empire.

The Depression provided an opportunity for the Commonwealth to become a genuine society brought together for the common good. But when the dominions and Britain came together at Ottawa in 1932, the result was acrimony and hard, self-interested bargaining.

The real power of the name was revealed in 1949. India, the country that had shed more blood for the empire than any other, and that had just wrenched itself free of the Empire’s grasp, became a republic. And yet it chose to retain the mystical connection, opting to remain within the Commonwealth.

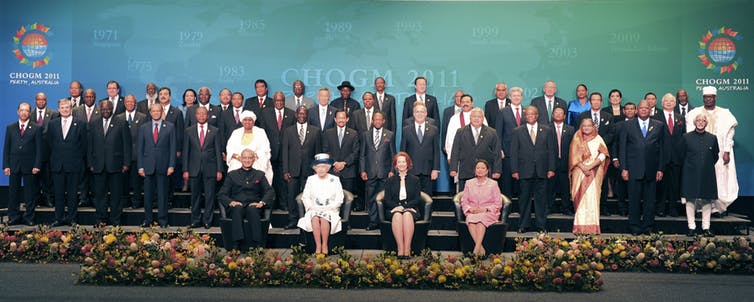

In the decades that followed, the Asian and African colonies – never even thought of as part of the original Commonwealth compact in 1917 – also chose enthusiastically to remain part of the mystical association.

By the 1960s, they were to turn an imperial club into a radically anti-racist force, taking the Commonwealth to the apex of its history in its campaigns against Rhodesia and apartheid.

Now, the Commonwealth’s once most oppressed societies are its most ardent supporters. Surveys show the most positive feelings about the Commonwealth are among those societies Deakin placed emphatically in the “ruled” category.

(Lafayette Negative Archive)

An organisation lacking a rationale

Today the Commonwealth exists as an organisation in search of a rationale. The mythology of the name has done its job: what brings the association together now is an act of forgetting what constructed it in the past.

Its bonds are not hard objectives of modern statecraft but a subterranean sentimentality of connectedness; it endures in its benignity because no-one has the heart to kill it off.

Its secretariat, a recent eminent persons’ group report, and the biennial meetings of its leaders all desperately try to find a rationale for its existence, loading fashionable issue after fashionable cause on its ramshackle shoulders – from green finance to fair trade.

It is hard to find an issue on which the Commonwealth has succeeded in bringing about genuine change since the demise of white rule in southern Africa.

When this coalition of whimsy meets a hard policy issue, its solidarity falls victim to its diversity, while its breadth of membership can’t deliver real weight and gravitas in the present day.

Where then does the Commonwealth sit, in the company of Persepolis and history’s empires? Surely as the last empire – the one that turned that word from a label of pride to one of accusation.

An empire determined to destroy and delegitimise the idea of empire itself.

An empire dedicated to the puncturing of its own pretensions to grandeur and permanence, under the reassuring myth of a mystical Arcadian community of free association.

Surely this is the enduring legacy of the British Empire – which is still so potent. We search in vain for the beginning of the unravelling; nor can we date its end.

Perhaps it continues, as Scotland, Wales and even England begin to assert themselves against the British Union as the original free association in the common interest.

![]() You can read other essays from Griffith Review’s latest edition here.

You can read other essays from Griffith Review’s latest edition here.

By Michael Wesley, Professor and Director of School of International Political and Strategic Studies, Australian National University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Explore top-rated compensation lawyers in Brisbane! Offering expert legal help for your claim. Your victory is our priority!

Explore top-rated compensation lawyers in Brisbane! Offering expert legal help for your claim. Your victory is our priority!

"

"