Five things you need to know Photo by AbsolutVision on Unsplash

Danielle Wood, Grattan Institute; Brendan Coates, Grattan Institute, and Kate Griffiths, Grattan Institute

Australia is living through the biggest economic and social disruption since the second world war. Today’s budget update provides a stark reminder of just how big the economic and budgetary fallout really is.

If you don’t have the appetite to wade through the 180-page economic statement, here are the five big takeaways.

Australian gross domestic product is expected to fall by 3.75% in 2020, before rebounding to grow by 2.5% in 2021, leaving GDP still 3% below pre-COVID levels mid next year.

The global outlook is bleaker.

Global GDP is forecast to contract by 4.75 per cent in 2020, the worst decline since the Great Depression in the 1930s, before rebounding to grow by 5% in 2021.

Australia’s official unemployment rate is now expected to rise from 7.4% today to a peak of 9.25% by Christmas, as most firms move off JobKeeper and many Australians who are without work start looking again.

Yet even this bleak set of numbers takes on a rosy hue against the backdrop of the worsening COVID-19 outbreaks in Victoria and NSW.

Treasury assumes the lockdown in Victoria will last just six weeks and outbreaks in NSW will remain localised. Neither outcome is assured, or even likely.

Meanwhile renewed outbreaks across the United States, Europe, and much of Asia point to the difficulty of reopening our economy safely while the virus remains active in the community.

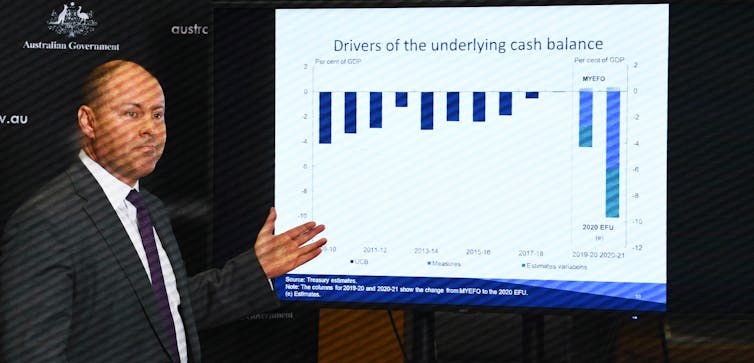

The headline deficits of A$85.8 billion last financial year and $184.5 billion this financial year are indeed “eye-watering” as the treasurer says.

The turn-around from the $5 billion surplus expected in December is a stark reminder never to count your chickens before they hatch.

But no one could have predicted a global pandemic.

The government has rightly spent big to support households and businesses through the crisis ($162 billion in 2019-20 and 2020-21). Shutdowns have hurt revenue too, with lower than expected company tax and goods and services tax collections, and a big drop in the forecast for personal income tax receipts because of the jump in unemployment.

Net debt is expected to reach 35.7% of GDP this financial year, the highest level since World War II. But it is worth remembering that debt reached more than 100% of GDP in the 1940s, and Australia’s debt levels have held at remarkably low levels by international standards since the 1970s, and remain relatively low even now.

Until this week, all of the government’s major crisis supports – including JobKeeper, the coronavirus supplement, and regulatory supports for businesses and households – were due to end abruptly in October, creating a fiscal cliff.

The government announced on Tuesday that it would extend the coronavirus supplement to December and JobKeeper to March, but both supports will be less generous, and JobKeeper will be more targeted. This means a cliff still looms in October, albeit with a slightly less deadly drop off.

Fiscal support will be $18 billion a month on average (10.7% of monthly GDP) until October, but this drops to $3 billion a month on average (1.9% of GDP) for the six months beyond. This will leave a big hole in economic activity, unlikely to be entirely filled by the private sector recovery.

As bleak as today’s economic forecasts are, the lack of any new fiscal stimulus announcements is even more striking.

The government has missed a golden opportunity to commit to new stimulus measures to support the recovery – something that most economists agree is needed.

Last month Grattan Institute estimated that $70-$90 billion in stimulus would be required over the next two years to bring unemployment down to below 5% and get wages growing again.

Today’s forecasts of a slower economic recovery, and the prospect of a worsening outbreak in Victoria, makes that stimulus even more urgent.

Stimulus takes time to roll out. Waiting for the October budget when we have already passed the cliff face means that money won’t hit the economy as fast as it needs to.

Despite the big headline deficits, now is not the time to panic about higher debt.

This is a once-in-a-century shock and using the balance sheet to cushion the blow, as the government has done, helps to ensure the costs of this crisis are more evenly shared across society and over time.

With interest rates at record lows, the interest burden is less than you might think.

The Commonwealth government can borrow for 10 years at an interest rate under 1%.

This means the additional $394 billion in net debt over the next two years will increase net interest payments by less than $4 billion a year, comfortably manageable within the current budget envelope.

Indeed, interest repayments are expected to remain lower than after the 1980s and 1990s recessions.

These debt levels are manageable over time in a growing economy. The bigger concern is that the government has not yet done enough to get the economy back on track.

Danielle Wood, Chief executive officer, Grattan Institute; Brendan Coates, Program Director, Household Finances, Grattan Institute, and Kate Griffiths, Fellow, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.