Lydia Edwards, Edith Cowan University

The shoe known in Australia as a “thong” is one of the oldest styles of footwear in the world.

Worn with small variations across Egypt, Rome, Greece, sub-Saharan Africa, India, China, Korea, Japan and some Latin American cultures, the shoe was designed to protect the sole while keeping the top of the foot cool.

Australians have long embraced this practical but liberating shoe — but history shows we can’t really claim to it as our own.

Geishas, workers, soldiers

Japan is often cited as the pivotal influence, perhaps because the culture features not only the thong’s closest ancestor (the flat-soled zori, traditionally made from straw) but also the chunky geta sandal, famously worn by geisha for centuries in an effort to keep trailing kimono hems out of the mud.

In the late 19th century, Japan started to export aspects of its culture to diverse corners of the world. An early example was the Hawaiian “slipper” or “slippah”, a thong-like version of the zori with roots in the footwear of Japanese plantation worker immigrants in the 1880s. The slipper rapidly became part of the Hawaiian sartorial code (as in Australia, the shoe suited the relaxed outlook and beach lifestyle).

The popularity of the shoe may have spread after US soldiers, stationed in the East Pacific during the second world war, brought back souvenirs — but that claim is contested.

During the 1940s the technology for mass-producing synthetic rubber was developed, and this undoubtedly increased dissemination and influence of the humble flip flop. However, it was not until around the same time Hawaii became the official 50th state of the USA in 1959 that thongs became a globally recognised symbol of leisure.

Downunderfoot

Despite the thongs’ strong identification with Australia, details of its exact arrival here are not easy to pin down.

From 1907 onwards, for example, advertisements described “Japanese sandals” with “flexible wooden” or jute soles, although the few illustrations that exist do not depict shoes with a thong fastening.

In 1924, Melbourne’s The Herald discussed criticism levelled at Melburnians for walking with a “flip-flop movement, bringing the back of the heel down too heavily on the ground, causing jarring to the body and fatigue”.

Heels were suggested as a remedy for women with this complaint. Nearly a century later, podiatrists still recommend avoiding thongs for long term wear. (These days, they’re not fans of heels either.)

In 1946, department store David Jones promoted “Olympia”, a Greek-inspired thong sandal with additional ankle straps. But it was not until around 1957, when Kiwi businessmen Maurice Yock and John Cowie both claimed credit for what they termed the “jandal” — a portmanteau of “Japanese” and “sandal” — that Australia’s connection with the flip flop became more established and, at the same time, questioned.

In 1959, Dunlop in Australia imported 300,000 pairs of thongs from Japan. They started producing them internally in 1960.

Read more: Take a plunge into the memories of Australia’s favourite swimming pools

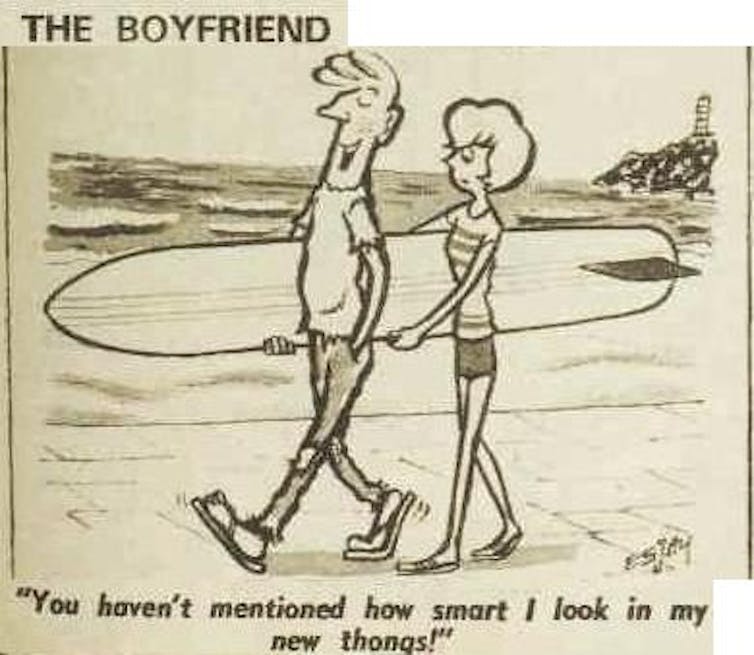

As Australia’s tourism boomed during the 1950s and 60s, so too did its sartorial image, with thongs taking centre stage as the footwear of choice for an egalitarian, laid-back society.

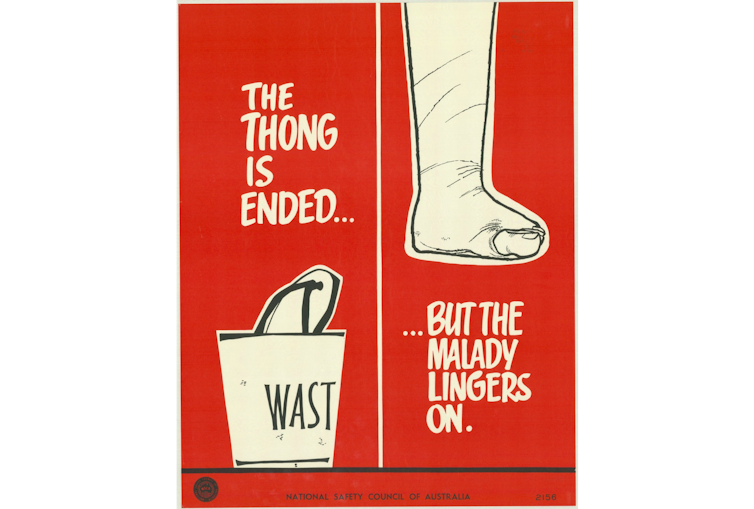

So widespread did they become, in fact, that by the mid 1960s bans were being sought by state governments to avoid frequent injuries at the workplace — especially construction sites.

In the name of professionalism, in 1978 the Queensland government decreed that schoolteachers not be permitted to wear thongs to work. This year, they have been banned for wear at Australia Day citizenship ceremonies — a decision reflecting a wish for greater “significance and formality” to be represented at official events.

But the rubbery love affair endured, perhaps shown most ardently when Kylie Minogue made her entrance as part of the Sydney 2000 Olympics atop a giant rubber thong carried by lifeguards.

Dressing up, dressing down

Thong-related concerns have not been limited to Australia.

In 2005 members of an American college women’s lacrosse team wore them to the White House to meet President Bush. There followed a furor over whether this brazen act was disrespectful, a distraction from the women’s achievements or signalled a casual shift in attitudes to leaders (and fashion) in the years after the Clinton sex scandals.

Since the late 1990s it has been possible to buy more formal heeled versions. Although these were widely mocked as expensive aberrations of the style, they looked to making a Kardashian-led comeback in recent times.

Branded versions are also available, with couturiers like Hermès selling a very unassuming flip flop for a cool A$600.

There is a poignant irony in the fact that thongs are the most popular kind of shoe in developing countries, precisely because of their cheap manufacture (often made from recycled rubber tyres) and consequently, very low purchase cost.

This practice of appropriating “ordinary” or “working class” clothing — transitioning it from the practical to the fashionable — is nothing new. We’ve seen it with singlets and boilersuits. Clogs are another footwear example.

Rather than a form of fashion whimsy, Australians take their thongs seriously. Even the naming of them — after the structural make-up of the shoe’s fastening rather than the onomatopoeic “flip flop” used by other countries — flies in the face of the Australian preference for shortened diminutives and nicknames.

That shows true commitment, but also that thongs are not really so dinky-di, after all.

Lydia Edwards, Fashion historian, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.