Muhammad Ali Nasir, University of Huddersfield

The eurozone’s latest economic growth figures are a little better than expected. This group of 19 EU nations grew 2.2% in the second quarter of 2021 compared to the first quarter, partly thanks to decent performances from Spain and Italy.

But while the US and Chinese economies are both now bigger than their 2019 peaks, the eurozone is 3% off that achievement. And when you look more broadly at the state of the eurozone, this turns out to be only the tip of the iceberg.

COVID-19 still overshadows everything around the world, but countries are likely to recover at different speeds once we get back to some sort of normality. This will depend on the structure of their economies, the effectiveness of their recovery policies, and how they deal with high sovereign debts and a foreseeable mix of weakish growth and inflation. But for several reasons, the eurozone particularly worries me.

Ghosts of the past

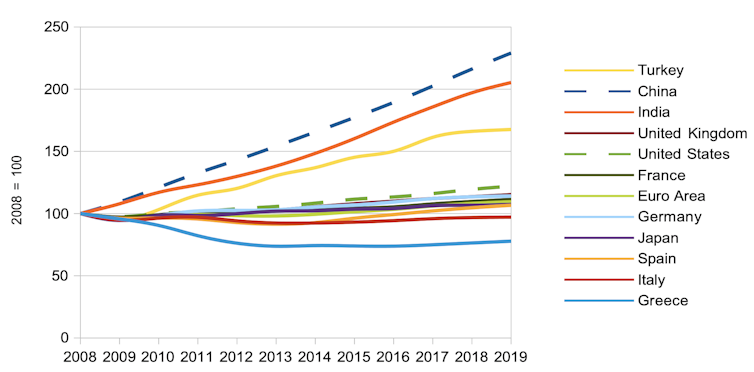

The first is the eurozone’s bleak performance since the global financial crisis of 2007-09. It took six years to regain its 2008 GDP level, and some members did even worse: Spain and Portugal took almost a decade, and Italy and Greece have yet to get there.

When COVID broke out, the eurozone growth rate remained well below its long-term trajectory. It was behind the US and UK, both of whom were hit harder by the global financial crisis, and even worse compared to the leading emerging economies. Neither was this a one-off. Looking at the past five recessions, the eurozone nations have been successively slower to recover from each one.

GDP by nation since 2008

Since 2008, the ECB has tried numerous measures to improve growth. Like most major powers, it has done a lot of quantitative easing (QE), which involves creating money to buy sovereign bonds and other financial assets. It has sought to prop up its retail banks in various ways, while also pioneering negative interest rates and giving the markets more forward guidance about monetary policy.

Famously in 2012, then ECB president Mario Draghi said he would do “whatever it takes” to save the euro. This forward guidance kept the euro stable, but the same cannot be said of growth.

Poor policy and low ammunition

Policy errors are partly to blame for this. With the benefit of hindsight, the eurozone went into the global financial crisis with lending rates on the low side, so had less room to cut than other regions. It was also more reluctant than central banks like the Bank of England and US Federal Reserve to start QE, preferring to focus on curbing inflation and making the euro “stabil wie die mark” (stable like the German mark). The ECB did not unveil a QE programme until 2015.

Countries with the capacity to spend to stimulate their economies, such as Germany, France and the Netherlands, also did too little. Spain’s stimulus was poorly designed, while Italy was more interested in balancing its books at the time. Too soon after the crisis struck, austerity then became the priority for the whole eurozone.

A related problem has been public and private investment. In middle-income EU regions, investment rates fell by about 14% between 2002 and 2018. In thrifty Germany, public and private fixed investments declined as a percentage of GDP for decades, despite a huge surplus in public spending.

Before COVID hit, EU infrastructure investment was at a 15-year low, with the greatest declines in regions that were already lagging. Initiatives intended to help, such as the European Economic Recovery Plan of 2008 and the European Commission Investment Plan in 2014, were too little.

The overall result was that weakness: Germany and the eurozone as a whole were showing 0% growth at the time of the COVID outbreak, while Austria, France and Italy were all contracting slightly. In response, the ECB had cut its main interest rate by 0.1 percentage points to -0.5% in September 2019, and restarted monthly QE to the tune of €20 billion (£17 billion) from November 1 of that year – the date Christine Lagarde became ECB president.

The eurozone economy was therefore needing life support even before the pandemic – indeed, many of the ECB’s other unconventional support measures were in place throughout. Tellingly, the ECB’s only new measure during the pandemic has been a new form of cheaper refinancing for banks. It raises the prospect of the ECB running out of the ammunition needed to keep stimulating the eurozone’s sickly economy.

Discipline über alles

Finally, some eurozone members are obsessed with the EU’s fiscal rules around low national debt and low deficits. The Financial Times may have reported in March 2020 that “Germany tears up fiscal rule book to counter coronavirus pandemic”, but there are already calls by influential figures such as Bundestag president Wolfgang Schäuble to return to fiscal discipline.

A rush to austerity 2.0 is a luxury that the EU cannot afford. To quote something often attributed to Albert Einstein, insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.

For different results, the ECB should stand its ground on monetary easing and, like the Fed, avoid giving in to inflationary pressures that are likely to be short term by raising rates or paring back QE.

Meanwhile, the fiscal rules need loosening to correspond to economic realities. The temptation must be avoided to throw the nations in the peripheries under the austerity bus again, one of the main causes of the eurozone crisis of the early 2010s.

Surplus nations, particularly Germany, should revive spending in infrastructure, education and technology. The EU’s €750 billion Next Generation EU investment plan will belatedly kick in later this year, but just like the two previous EU recovery packages, will probably not be enough on its own.

With an unimpressive track record on recovery, inherently weak economies, an obsession with fiscal rules and the prospect of the ECB running out of ammunition, the alternative could be a second lost decade. What that could do to the eurozone and the EU, it would be better not to find out.

Muhammad Ali Nasir, Associate Professor in Economics and Finance, University of Huddersfield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.