Brendan Coates, Grattan Institute and Matthew Cowgill, Grattan Institute

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s announcement that he’ll prioritise reducing unemployment ahead of reducing government debt is welcome news.

The government is required by the Charter of Budget Honesty to develop and publish a fiscal strategy to be used in each budget.

The one that it has been using doesn’t mention unemployment at all and instead talks about offsetting new spending “by reductions in spending elsewhere” and commits it to “achieve budget surpluses, on average, over the course of the economic cycle” – something that’s not going to happen for a long time.

A realistic fiscal strategy is a good idea. A lot of behaviour is driven by expectations. If consumers and businesses think the government is going to slash and burn its way to a surplus, any stimulus in the meantime will be less effective.

People are more likely to save, and businesses less likely to hire, if they think tax hikes and spending cuts are around the corner.

A clear statement that is not the case will help.

But the Treasurer’s pledge to keep running deficits “until the unemployment rate is comfortably back under 6%” is nowhere near ambitious enough.

Former US Federal Reserve Chairman William McChesney Martin Jr. once famously said that the central bank’s role is “to take away the punch bowl just as the party gets going”.

Tightening budget policy – raising taxes or cutting spending – when unemployment crosses the 6% mark would be packing away the booze when many of the guests haven’t even arrived.

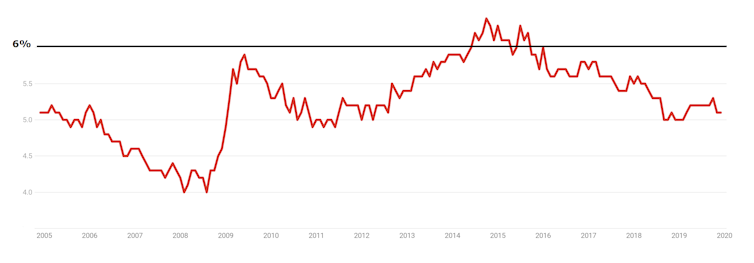

In the 15 years before COVID-19 struck, Australia’s unemployment rate had been above 6% only briefly, between mid 2014 and early 2016.

Unemployment rate, 2015 – 2019

The unemployment rate was well below 6% before the pandemic struck, yet the labour market was clearly running below its potential.

Before the pandemic, the Reserve Bank revised down its estimate of the unemployment speed limit – the unemployment rate at which inflation and wages would accelerate – from 5% to around 4.5%.

The Treasurer should wait until we’re closer to that speed limit before reaching for the brakes. The difference between 6% and 4.5% unemployment might not sound like much, but it amounts to an extra 200,000 people or so in work.

And it affects the rest of us too. Most Australians won’t get anything more than modest pay rises until the labour market tightens.

The danger is declaring victory too soon

The government handled the acute phase of this crisis well, although not perfectly. It deserves credit for moving very quickly to support the economy. But the danger now is that it turns too soon to budget tightening, stunting a nascent recovery.

This is the mistake many governments and central banks made after the global financial crisis – acting commendably to shore up activity in the crisis phase, but then pulling away support before enough of the damage had been repaired.

With interest rates so low, the government has a lot of capacity to run deficits without the debt-to-GDP ratio getting out of control.

As Frydenberg noted, “with historically low interest rates, it is not necessary to run budget surpluses to stabilise and reduce debt as a share of GDP — provided the economy is growing steadily”.

It’s a point made by former IMF Chief Economist Olivier Blanchard in one of the most influential recent papers in economics – his 2019 presidential address to the American Economics Association.

Blanchard noted that when the interest rate on government debt is less than the nominal growth rate of the economy, “public debt may have no fiscal cost”.

We’ve access to money for nothing

The Australian government can borrow for 10 years at a fixed interest rate of about 0.9%. It recently issued 30-year fixed-rate bonds for less than 2%.

Both are less than the Reserve Bank’s inflation target, suggesting that over time in real terms the money will cost nothing.

Over the past five years, Australia’s nominal growth rate has averaged 4%. The most recent Intergenerational Report projected average nominal growth of 5.25% a year for 40 years.

Even if economic growth falls well short of that projection it is hard to imagine it going below the rate at which the government can borrow for very long.

That means debt is likely to remain manageable relative to the size of the economy, and debt servicing costs will be modest, particularly compared to the benefits of stimulus.

Over the medium-term the government will need to ensure its debt is sustainable and does not continue to rise as a share of the economy.

But rushing too quickly to “repair” the budget position would be an economic ‘own goal’ – hampering job creation, economic growth, and ultimately the bottom line it sought to protect.

Reserve Bank Deputy Governor Guy Debelle said this week that “absent the fiscal stimulus, the economy would be significantly weaker and debt levels even higher”.

He is right. Taking the foot off the economic accelerator when unemployment is at 6% would condemn Australia to a long and slow recovery. It’s not in the Treasurer’s interest, and it’s not in ours.

Brendan Coates, Program Director, Household Finances, Grattan Institute and Matthew Cowgill, Senior Associate, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.