Julie Boland, University of Michigan

During the pandemic, video calls became a way for me to connect with my aunt in a nursing home and with my extended family during holidays. Zoom was how I enjoyed trivia nights, happy hours and live performances. As a university professor, Zoom was also the way I conducted all of my work meetings, mentoring and teaching.

But I often felt drained after Zoom sessions, even some of those that I had scheduled for fun. Several well-known factors – intense eye contact, slightly misaligned eye contact, being on camera, limited body movement, lack of nonverbal communication – contribute to Zoom fatigue. But I was curious about why conversation felt more laborious and awkward over Zoom and other video-conferencing software, compared with in-person interactions.

As a researcher who studies psychology and linguistics, I decided to examine the impact of video-conferencing on conversation. Together with three undergraduate students, I ran two experiments.

The first experiment found that response times to prerecorded yes/no questions more than tripled when the questions were played over Zoom instead of being played from the participant’s own computer.

The second experiment replicated the finding in natural, spontaneous conversation between friends. In that experiment, transition times between speakers averaged 135 milliseconds in person, but 487 milliseconds for the same pair talking over Zoom. While under half a second seems pretty quick, that difference is an eternity in terms of natural conversation rhythms.

We also found that people held the floor for longer during Zoom conversations, so there were fewer transitions between speakers. These experiments suggest that the natural rhythm of conversation is disrupted by videoconferencing apps like Zoom.

Cognitive anatomy of a conversation

I already had some expertise in studying conversation. Pre-pandemic, I conducted several experiments investigating how topic shifts and working memory load affect the timing of when speakers in a conversation take turns.

In that research, I found that pauses between speakers were longer when the two speakers were talking about different things, or if a speaker was distracted by another task while conversing. I originally became interested in the timing of turn transitions because planning a response during conversation is a complex process that people accomplish with lightning speed.

The average pause between speakers in two-party conversations is about one-fifth of a second. In comparison, it takes more than a half-second to move your foot from the accelerator to the brake while driving – more than twice as long.

The speed of turn transitions indicates that listeners don’t wait until the end of a speaker’s utterance to begin planning a response. Rather, listeners simultaneously comprehend the current speaker, plan a response and predict the appropriate time to initiate that response. All of this multitasking ought to make conversation quite laborious, but it is not.

Getting in sync

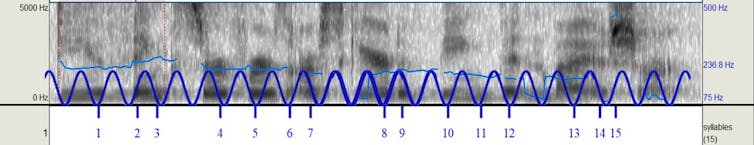

Brainwaves are the rhythmic firing, or oscillation, of neurons in your brain. These oscillations may be one factor that helps make conversation effortless. Several researchers have proposed that a neural oscillatory mechanism automatically synchronizes the firing rate of a group of neurons to the speech rate of your conversation partner. This oscillatory timing mechanism would relieve some of the mental effort in planning when to begin speaking, especially if it was combined with predictions about the remainder of your partner’s utterance.

While there are many open questions about how oscillatory mechanisms affect perception and behavior, there is direct evidence for neural oscillators that track syllable rate when syllables are presented at regular intervals. For example, when you hear syllables four times a second, the electrical activity in your brain peaks at the same rate.

There is also evidence that oscillators can accommodate some variability in syllable rate. This makes the notion that an automatic neural oscillator could track the fuzzy rhythms of speech plausible. For example, an oscillator with a period of 100 milliseconds could keep in sync with speech that varies from 80 milliseconds to 120 milliseconds per short syllable. Longer syllables are not a problem if their duration is a multiple of the duration for short syllables.

Internet lag is a wrench in the mental gears

My hunch was that this proposed oscillatory mechanism couldn’t function very well over Zoom due to variable transmission lags. In a video call, the audio and video signals are split into packets that zip across the internet. In our studies, each packet took around 30 to 70 milliseconds to travel from sender to receiver, including disassembly and reassembly.

While this is very fast, it adds too much additional variability for brainwaves to sync with speech rates automatically, and more arduous mental operations have to take over. This could help explain my sense that Zoom conversations were more fatiguing than having the same conversation in person would have been.

Our experiments demonstrated that the natural rhythm of turn transitions between speakers is disrupted by Zoom. This disruption is consistent with what would happen if the neural ensemble that researchers believe normally synchronizes with speech fell out of sync due to electronic transmission delays.

Our evidence supporting this explanation is indirect. We did not measure cortical oscillations, nor did we manipulate the electronic transmission delays. Research into the connection between neural oscillatory timing mechanisms and speech in general is promising but not definitive.

Researchers in the field need to pin down an oscillatory mechanism for naturally occurring speech. From there, cortical tracking techniques could show whether such a mechanism is more stable in face-to-face conversations than with video-conferencing conversations, and how much lag and how much variability cause disruption.

Could the syllable-tracking oscillator tolerate relatively short but realistic electronic lags below 40 milliseconds, even if they varied dynamically from 15 to 39 milliseconds? Could it tolerate relatively long lags of 100 milliseconds if the transmission lag were constant instead of variable?

The knowledge gained from such research could open the door to technological improvements that help people get in sync and make videoconferencing conversations less of a cognitive drag.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

Julie Boland, Professor of Psychology and Linguistics, University of Michigan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.