The Conversation is running a series of explainers on key figures in Australian political history, looking at the way they changed the nature of debate, its impact then, and it relevance to politics today. You can read our piece on Julia Gillard here.

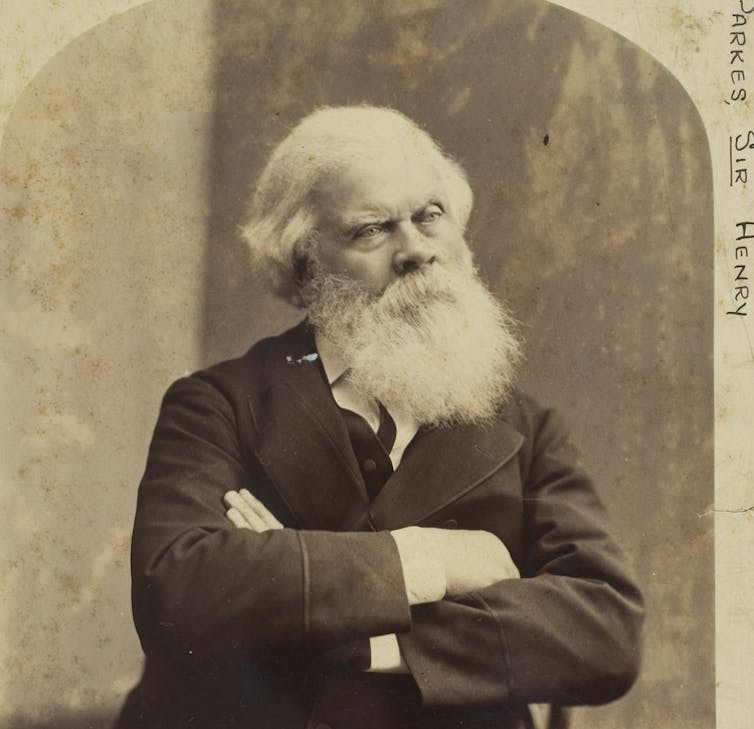

Henry Parkes, known today as the “Father of Federation”, set in motion the process that led to the joining of Australia’s six colonies in 1901 – a significant moment that heralded the birth of a new nation.

While he did not live to see the outcome – he died five years before the establishment of the Commonwealth of Australia – Parkes had been the driving force behind the idea of federation and a key architect of the process that ultimately created it.

Parkes’s vision was to unite the British colonies into a self-governing and democratic nation that spanned the continent. The new country would have a constitution written by Australians, but would remain “under the British crown” in an enduring relationship with the land of his birth.

Perhaps the most defining moment of his political career came in 1889, when he gave his Tenterfield Oration. Much like US President Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in 1863, Parkes’ speech was little reported at the time, but later took on legendary status.

The great question which we have to consider is, whether the time has not now arisen for the creation on this Australian continent of an Australian government and an Australian parliament … Surely what the Americans have done by war, Australians can bring about in peace.

From radical ideas to a career in politics

Parkes was born in Warwickshire, England, in 1815 into a family of poor tenant farmers. After his family was forced off the farm by debt in 1823, he later worked in Birmingham and London.

In 1838, Parkes moved to New South Wales as a bounty migrant with his young wife and developed considerable talent as a journalist. This was all the more remarkable given he was largely self-educated.

He eventually gravitated to politics and associated himself with the radical patriots in the colony. With these radicals, Parkes pushed for universal suffrage, the transformation of the Australian colonies into a federal republic and, above all, for free trade. He also campaigned against the transportation of convicts from the UK.

Parkes later moved away from radicalism and republicanism, deciding he could achieve more in government. When New South Wales achieved control over its local affairs in the 1850s, Parkes joined the legislative assembly as one of a small group of liberals.

Parkes devoted his career to politics, moving through the ranks of the pro-free trade liberals to serve five terms as premier of New South Wales from 1872-91.

Parkes advocates for a federal council

After the separation of Queensland from New South Wales in 1859, there were five self-governing colonies in eastern Australia. The colonies were competitive and largely concerned with their own affairs. Federation was not a pressing issue.

Parkes was still relatively new to politics in the 1860s, but he nonetheless became a tireless crusader for his idea of a colonial union. As NSW colonial secretary, he proposed establishing a federal council of representatives from all five colonies in 1867, and again as premier in 1880. Both times, it went nowhere.

However, a few years later, the colonies finally began to see the benefits of a stronger federation, due to unease over the expanding influence of the French and Germans in the Pacific. All except NSW ultimately supported the establishment of the federal council in 1885.

The new council had limited legislative powers and no permanent executive powers or revenues of its own. The absence of NSW also weakened it.

Nonetheless, it was the first major form of inter-colonial cooperation. The council also allowed federalists to meet and exchange ideas, setting in motion the more ambitious campaign for federation led by Parkes.

The Tenterfield address and dawn of federation

By the end of the 1880s, opinion was divided over the future of the Australian colonies. While some advocated to “cut the painter” and separate from Britain, others preferred to protect the current system.

The concept of an “imperial federation” with a single federal state consisting of the UK at the centre and the self-governing colonies was also gaining popularity.

One of the primary obstacles to federation was the struggle between New South Wales, which supported free trade, and other colonies like Victoria, which advocated protectionism. Parkes was able to neutralise this problem by proposing that once a federation was created, a Commonwealth parliament could legislate on tariff policy.

In 1889, Parkes grasped the nettle. He proposed to the Victorian government that the colonies should appoint delegates to a convention, which would draw up the constitution for a nation and discuss its relationship with Britain.

Later that year, Parkes travelled to Queensland armed with a report on colonial defence to garner Queensland’s support for his cause. On his return journey, he delivered his famous address at Tenterfield calling for “a great national government for all Australia”.

In 1890, Parkes finally succeeded in putting together an informal colonial conference in Melbourne that led to the first National Australasian Convention in Sydney the following year. It was a revolutionary moment for the future country and produced the fundamentals of the federal system we have today.

Led by Parkes, the delegates in Melbourne and Sydney sketched out a House of Representatives, representing the people, and a Senate representing the colonies (later states). They also specified powers for the Commonwealth and the states, and envisioned a High Court to interpret the constitution.

Both conventions were a triumph for Parkes. Alfred Deakin, a young Victorian legislator at the time, noted he was

from first to last, the chief and leader.

More conventions were held over the coming years to iron out the details of a bill that was finalised in 1899 and transmitted to the UK for ratification by the British parliament.

Parkes’s legacy today

Parkes’s championing of the federal movement transformed Australia’s political agenda at a time when the colonies were still content to chart separate courses.

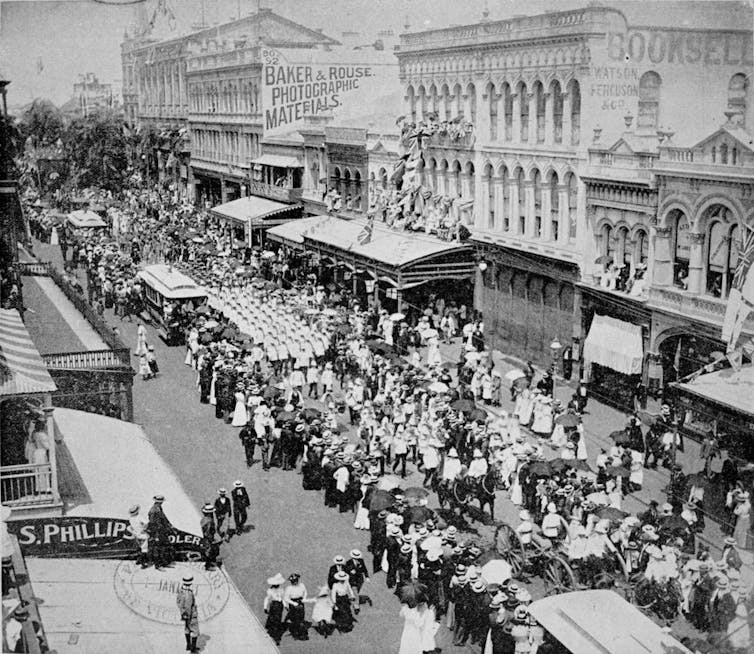

After his death, referendums were held in all the colonies in 1899 and 1900 and the people voted “yes”. Australia finally became a federation on January 1 1901.

In the federation procession in Melbourne in 1901, Parkes was the only leader who received public homage, with his image and slogans festooned on signs and other paraphernalia. Other politicians, including the country’s first prime minister, Edmund Barton, yielded him the preeminent position in the pantheon of federation fathers.

After 120 years, Australians take federation as a given. But had it not been for Parkes, Australia would probably not have become a nation in 1901, and the system of government we have today might well be very different.

David Lee, Associate Professor of History , UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.