Michael Herron, Dartmouth College and Daniel A. Smith, University of Florida

Tens of millions of Americans have already cast their ballots for the 2020 election by mail, building on a historic shift in voting methods that started with primary elections held during the COVID-19 pandemic.

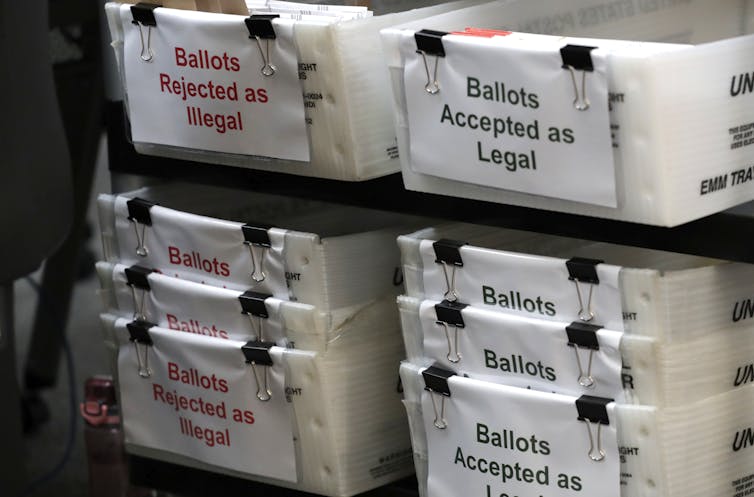

Mail-in ballots, however, aren’t automatically accepted as in-person ballots are. Rather, they can be rejected if they have signature defects on their return envelopes. Unless cured by voters – which means that voters fix the signature errors on them – these submitted ballots will be rejected.

Thanks to ongoing reporting of voter turnout in two battleground states, Florida and North Carolina, we can identify the number of mail-in ballots at risk of being rejected. So far, we can tell that there are thousands of ballots flagged for rejection in these two states. In addition, racial minorities and Democrats are disproportionately more likely to have cast mail ballots this election that face rejection.

The signature issue with mail ballots

Above, we use the word “risk” when describing ballots in Florida and North Carolina that have been flagged for rejection. While these ballots have signature defects, they have not yet been formally rejected.

Not all states have the same requirements for mail-in voting, but ballots usually face rejection if they’re missing a voter’s signature. Another source of defects is an ostensibly mismatched signature. This happens when an elections official concludes that a voter’s signature on a return envelope doesn’t match the voter’s signature on file.

Some states, like North Carolina, require witness signatures on ballot return envelopes, with the lack of such a signature considered a defect.

Enough ballots face rejection to sway an election

Our counts of mail ballots facing rejection in Florida and North Carolina are conservative. When calculating them using official data, we assume that any inconsistencies we find in the data are resolved in favor of ballot acceptance.

That said, here is what we know as of Oct. 22.

In Florida, 3,210,873 voters have cast mail ballots, and of these, 15,003 ballots face rejection, corresponding to a potential ballot rejection rate of 0.47%. This rate is not an estimate. It is based on counts drawn from official statewide data.

These thousands of mail ballots currently in limbo can make a difference. Consider the 2018 midterm election. In his successful United States Senate bid in this contest, Republican Rick Scott beat incumbent Democrat Bill Nelson by only 10,033 votes.

Over 2 million Floridians have yet to return the mail ballots sent to them by county election officials, so the number of mail ballots subject to rejection in Florida could grow well beyond 15,000.

In North Carolina, an even greater percentage of mail ballots face rejection. In that state, 8,228 of 701,425 mail ballots fall into this category, yielding a potential rejection rate of 1.2%.

As in Florida, North Carolina’s elections can be extremely close. In the state’s 2016 gubernatorial race, a mere 10,277 votes out of roughly 4.6 million cast separated the winner, Democrat Roy Cooper, from incumbent Republican Pat McCrory. The number of ballots at risk in North Carolina – 8,228 – remains smaller than this margin but could grow as more ballots are returned.

Partisan and race-based ballot rejection rates

The risks of mail ballot rejection are not spread uniformly across voters, and rejected mail ballots are not politically neutral.

We can see from our Florida and North Carolina election data that registered Democrats have greater rejection rates than Republicans. The partisan differences in potential ballot rejection rates – Democratic rate minus Republican rate – are approximately 0.07% and 0.16% in Florida and in North Carolina, respectively.

In addition, Democrats have expressed a greater willingness to vote by mail than Republicans – though this might be changing. This will compound any biases caused by differing ballot rejection rates across Democratic and Republican voters.

Official election data in Florida and North Carolina also reveal a clear racial pattern among mail ballots facing rejection: Black and Hispanic voters are much more likely to have their ballots flagged for missing signatures or other discrepancies than are white voters.

In Florida, ballots cast by Hispanic voters face a rejection risk 2.6 times that of white voters. In North Carolina, where the two most common racial groups are Black and white, the risk of ballot rejection for Black voters is three times that of white voters. White voters thus have lower ballot rejection rates than minority voters, who tend to support Democratic candidates over Republican ones.

Ballots can still be ‘cured’

In both Florida and North Carolina, voters who have submitted mail ballots with signature defects can still cure them.

Florida voters have the opportunity to fix their mail ballots through Thursday, Nov. 5. This can be done via affidavit. Details about ballot curing in North Carolina were until recently tied up in court. But voters in the state can now, in some cases, fix ballots with defects. However, ballots in North Carolina missing witness signatures cannot be cured, and voters in the state who cast these types of ballots must request new ballots if they want their votes to count.

Curing a ballot with a signature defect requires knowing that it is facing rejection. But not all states send out notices informing voters of ballot defects.

In some states, voters who cast mail-in ballots can check on the status of their ballots with local officials or using web resources provided by the secretary of state, which voters can do in New Mexico and Ohio.

However, other states, such as Maine and New Hampshire, don’t have laws mandating that voters get the opportunity to cure mail ballots of deficiencies. For this election, though, officials in these two New England states have developed procedures to allow voters to fix ballots with defects.

Given the surge of mail-in ballots in this election cycle, there’s likely to be confusion over rejected ballots and cures. In the future, it’ll be important for states to provide voters with transparent processes for fixing defective ballots so they can ensure they’ll be able to exercise the right to vote.

Michael Herron, William Clinton Story Remsen ’43 Professor of Government, Dartmouth College and Daniel A. Smith, Professor and Chair of Political Science, University of Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.