Tulasi Srinivas, Emerson College

Massive crowds are expected to gather at India’s northern city of Haridwar throughout April 2021 for the religious festival of Kumbh Mela, despite the country’s grappling with a COVID-19 surge.

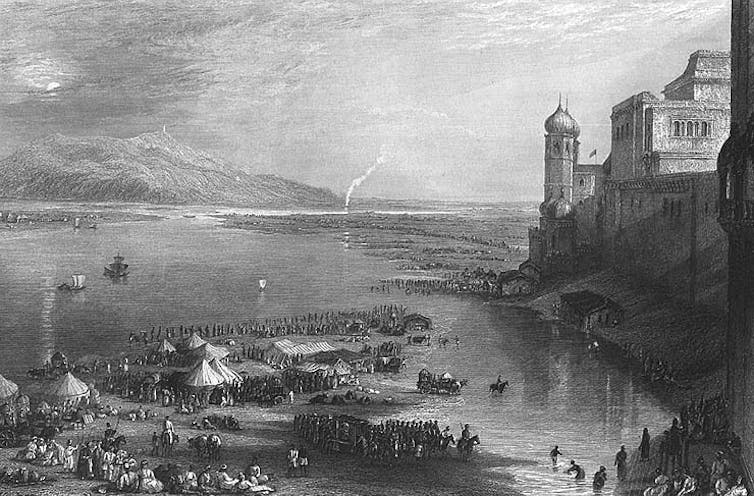

The Kumbh Mela is a Hindu pilgrimage held every 12 years at sacred tirthas, or river-ford sites, along the Ganges River in India.

This year the government expects over a million pilgrims a day to bathe in the sacred river. Over 5 million people are expected per day on the most auspicious days – April 12, 14 and 21 – for a total of a 100 million celebrants.

As a scholar of Hinduism, I celebrate this peaceful mammoth congregation of humanity. Shaped by mythology, astrology and society over the long course of history, this festival is the largest religious gathering of its kind in the world.

Rooted in Hinduism’s ancient theological texts, the bathing ritual has survived wars, revolution and famine – but its biggest threat has been epidemic diseases. Authorities from the colonial British government of the 19th century to the Indian government today have had to contend with the challenge of managing the spread of contagion during this huge gathering of people.

Festival of immortality

The festival celebrates the Hindu myth of Samudra manthan – the churning of the cosmological ocean by the gods and demons to get the nectar of immortality, known as amrita.

In the fight that ensued for the amrita, several drops of the elixir fell to Earth, sanctifying the waters where they landed. The word Kumbh refers not only to the pot of nectar spilled on its way to the heavens, but also to the astrological sign of Aquarius, the water carrier, the time when the Kumbh Mela takes place. Hindus believe that bathing in the sacred Ganges on the auspicious days of the festival leads to salvation from the endless cycle of reincarnation.

The traditional start date of the Kumbh, Makara Sankranti, or the winter solstice, is in January. However, this year the festival was delayed by the Indian government because of fears of the spread of COVID-19.

Colonial Kumbh

The festival is mentioned in British colonial records. In 1812 the archives of the British East India Co., a joint stock company that had been formed in 1600 to engage in trade with India, mention a “great” congregation of people at the “melah” that had not occurred in 28 years. Historians of religion have noted that the British conflated another ancient fair, which went by the name Magha Mela, with the Kumbh Mela.

At the time, the East India Co. imposed a “pilgrim tax” on participants, even though it did not provide infrastructure or amenities.

The East India Co. ruled India for the British Crown from 1757, and the company-crown alliance lasted a century until the Indian rebellion of 1857. During that time the British administration, in collaboration with the local police and heads of pilgrim organizations, made attempts to improve the infrastructure of the Kumbh Mela, including laying new railway lines, widening the access roads and building bigger bathing platforms, or ghats. They hoped to increase access, prevent pilgrim stampedes near the waters edge and garner better revenue.

Inadvertently, the British helped legitimize and popularize the Kumbh Mela as the supreme sacred festival. At the same time, they believed the Kumbh was a political gathering where revolutionary and nationalistic ideas took birth.

Politics of Kumbh

Until 1801, before the colonial rule in the state, the Kumbh Mela was controlled and managed by sects, or “akharas,” of militant ascetics who fought for the privilege of bathing first, as going first conferred power and status. These were often violent battles of alarming scale in which thousands died.

But the akharas skillfully managed the logistical challenge of the massive pilgrimage and festival. They organized hostels and food, provided policing, and oversaw the arbitrating of disputes over congregant living facilities. They also instituted and collected pilgrim taxes. The ascetics of the akharas engaged in religious discourses and philosophical lectures. Their presence was an attraction for ordinary pilgrims who sought their audience and blessings.

But by 1858 the British Crown controlled all of India and attempted to take over the logistics and rules for the Kumbh Mela, particularly for pilgrims’ movement at the site, to avoid stampedes and upgrade the sanitary conditions. At the time legal agreements over the bathing order ensured an end to the violence between the akharas.

The British allowed and instituted an order for the ascetics of 14 akharas to bathe on the three auspicious bathing days of the mela. Following Indian independence, subsequent Indian governments have also tried to control the crowds and organize the akharas’ bathing schedule.

Fear of contagion

The first British reference that specifically mentioned the Kumbh Mela was made in an 1868 report that stated the need for increased and tighter sanitation controls at the “Coomb fair” to be held in January 1870. Recognizing the threat of rapid spread of contagion among the crowds, the British government attempted to sanitize and control the hundreds of thousands of pilgrims at the Kumbh.

In 1870 the Pioneer newspaper, the voice of the British in the northern city of Allahabad, said that the control of crowding was seen as a “well-directed activity towards averting, or at any rate mitigating, the ravages of disease” among pilgrims. The spread of disease was viewed as a threat to the possible collection of taxes and governance.

Between 1892 and 1908, when major famines, cholera and plague epidemics struck in British India, the colonial government controlled entry to the Kumbh, citing hygiene concerns. Pilgrims dropped to a low of around 300,000 as reported by the Imperial Gazetteer. In 1941, the British government banned sale of tickets amid rumors that Japan, in advance to entering World War II, was to bomb Allahabad where the Kumbh was slated to take place.

Rising religiosity

In the past century the Kumbh has become so popular that “half” versions – Ardh Kumbh – are held every six years.

The dramatic arrival of the akharas – that includes 14 sects of Hindu and Sikh ascetics as well as warrior monks often illustrated with exoticized photographs – has become the signature visual of the Kumbh.

These tens of thousands of ascetics, some dressed in saffron robes, some nude and covered in ash, with wild dreadlocks, come riding on horseback, or in golden seats on elephants. The processions are accompanied by loud drumming, conch blowing and the sound of gongs as they enter the sacred water, in wave upon wave of humanity.

COVID controls

This year’s event takes place amid fears that a massive gathering like this could turn out to be a COVID-19 superspreader event. According to Johns Hopkins University, by April 1, 2021, the start of the Kumbh Mela, India had reported 12 million cases and 162,900 deaths.

The Indian government has issued several directives to control the spread of the disease: Thermal screening checkpoints have been set up, and efforts are being made to sanitize all restrooms and sleeping quarters. Strict protocols for participation in the Kumbh have been issued, including a limited time period of half an hour for each akhara to bathe. Furthermore, the government has stated that after April 1 all visitors to the Kumbh have to produce evidence of a recent negative COVID-19 test.

However, even before the Kumbh began, the city and neighboring areas had already emerged as COVID-19 hot spots. As the festival began, seven living Hindu saints in the city of Haridwar tested positive, and 300 pilgrims were found positive during the first few days of the festival.

Images emerging from Haridwar of millions of the faithful, praying, eating and bathing, often maskless and in close proximity with one another, are raising fears about how the desire for the divine nectar of immortality might turn out in a pandemic year.

[This week in religion, a global roundup each Thursday. Sign up.]

Tulasi Srinivas, Professor of Anthropology, Religion and Transnational Studies, Institute for Liberal Arts and Interdisciplinary Studies, Emerson College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.