Brigitte Granville, Queen Mary University of London

The US Federal Reserve has just reassured the markets that it doesn’t expect inflation to get out of hand in the coming months. It comes as concerns about serious inflation damaging the global economy have reached fever pitch, particularly since recent Labor Department data showed that American inflation rose 4.2% over the 12 months ended April – the highest since the global financial crisis of 2007-09. In the euro area, inflation seems certain during the rest of this year to break out above the European Central Bank target of “close to but below 2%”.

Central bankers on both sides of the Atlantic say that these price rises are a temporary consequence of the whiplash effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on demand. Supply chains in everything from commodities to semiconductors have been disturbed by demand first collapsing and then surging back, making prices very volatile. On this rationale, inflation will settle down once the pandemic recedes.

Critics point to the risks of price pressures setting off a chain reaction where everyone expects future price rises, causing a true inflationary episode where prices persistently increase across the board.

This debate about the near-term outlook is matched by an equally lively debate about long-term inflation, relating to drivers such as the effect of baby boomers retiring, China’s changing labour force, automation and so on. So who is right in all this? Are the inflation numbers a blip or are we seeing a gathering storm?

Lessons of the 2010s

In Remembering Inflation, a book I published in 2013, I attempted to weave together various strands of this subject by looking at the breakthroughs in economists’ thinking about the causes and cures of inflation inspired by the “stagflation” of the 1970s, where inflation and unemployment both sharply increased.

My timing with that book was poor. The global economy’s faltering recovery from the global financial crisis was characterised by the opposite problem – deflation – where people expect prices to fall. As overstretched firms and households retrenched during the early 2010s, it should have fallen to governments to generate needed demand by ramping up public spending. Instead, fashionable notions of balancing the books using austerity got in the way.

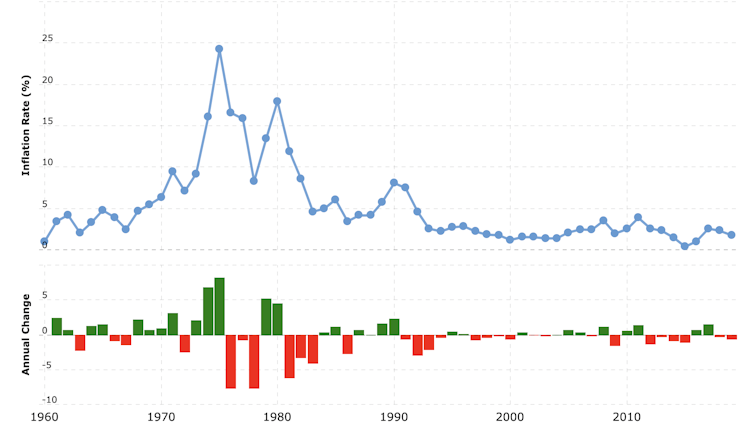

UK inflation rate 1960-2021

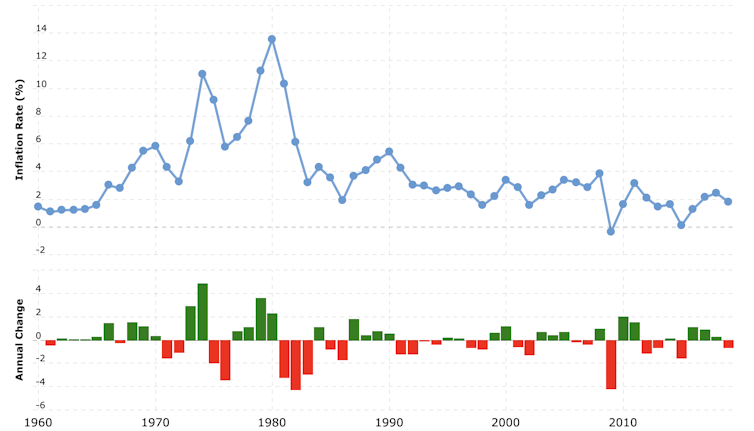

US inflation rate 1960-2021

Central banks were left to do the heavy lifting through cutting headline interest rates and using unconventional monetary policies like quantitative easing (QE) – that is, “printing money” – to buy large quantities of government bonds and other financial assets.

This helped to drive down long-term interest rates – even into negative territory in Europe – making things like mortgages and business loans cheaper. Yet the only “inflation” that resulted was rising asset prices in everything from property to stocks and shares. It made the rich richer, engendering even wider inequalities than before.

All the while, official consumer price inflation – which refers to the average change in prices of a basket of specific household goods – remained persistently below the 2% level targeted by the major central banks. According to what is known as the Phillips curve, inflation should have been stimulated by the fact that unemployment fell in countries such as the UK, but it turned out this relationship had been suspended.

One reason – particularly apparent in the US – was that the falling rate of unemployment was flattered by increasing numbers of people giving up looking for work and dropping out of the labour force altogether. This was a symptom of the core problem of insufficient demand from businesses and consumers.

A related symptom was the structural shift in the labour market. Where new jobs were created – sometimes, as in the UK, even to the extent bringing people back into the labour force – these were concentrated in low-skilled and low-paid openings in sectors like leisure, hospitality and logistics. Increased demand for such services was the meagre limit of the “trickle-down” effect from ever-richer asset owners.

All this meant that there was not much real wage growth which, along with associated increases in bank lending, is essential for creating inflation. So it was that, in the 2010s, monetary policy not only failed to stimulate the economy but actually proved counterproductive.

Stimulus and the pandemic

During the pandemic, the situation has been different. Central banks have again been trying to stimulate the economy by expanding QE, but governments have also been using debt-funded spending to substitute for the normal demand that has disappeared because of the shutdowns.

Major governments seem determined to correct the flawed policies of the past decade. This is especially true of the Biden administration, whose massive programme of increased spending aims to drive up labour participation and wages – thereby avoiding the deflationary troubles of the 2010s.

The administration is firmly supported in this by Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell. In August 2020, the central bank changed its inflation policy to “average inflation targeting”. Whereas in the past, the Fed targeted 2% inflation and would raise interest rates in response to low unemployment in the belief that inflation would otherwise start rising, it is now ready to allow inflation to rise to say 3% in the name of increasing employment to help stimulate economic recovery.

The success of this strategy depends on demand for more workers materialising from US businesses. But critics like Larry Summers, the former Democratic treasury secretary, argue that the government’s fiscal stimulus will create demand beyond the economy’s present production potential, risking persistent inflation.

The administration and its supporters counter that there is more slack in the economy than people like Summers believe, because so many discouraged workers have dropped out, and higher production of goods and services will result from reversing the long dearth of domestic business investment.

All such happy effects will, according to the plan, flow from using government spending to generate demand. The jury remains out on whether this will cause unmanageable inflation – either in America or, potentially, in Europe if the ECB, together with the EU and its member states, follow their apparent inclination to emulate the US.

A danger and an opportunity

Returning to my own studies of the exit from the “great inflation” of the 1970s, two lessons emerge that should help the jury in its deliberations about where we go from here. One points to an opportunity, the other to a danger.

The first lesson has to do with confidence and the expectations of firms and households, which dominate any discussion about inflation. The 1970s inflation was only really subdued after central banks were given operational independence from politicians to pursue low and stable inflation. As monetary policy became more credible, people no longer expected prices to rise so fast.

This was the main reason for the flattening of the Phillips curve – that is, inflation no longer jumps up smartly as unemployment falls. Present-day policies to stimulate demand benefit from well anchored inflation expectations. Put bluntly, policymakers will “get away” with more stimulus before having to pay an inflationary price, and this should improve their chances of success.

A key figure in the development of such thinking about expectations in the 1970s-80s was the American economist Thomas Sargent. His work on “systematic changes in inflation policy” also underlies the second – and more cautionary – lesson for today’s policymakers and the present inflation outlook.

This was crystallised in a 1982 paper by Sargent and Neil Wallace called Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic showing that monetary and fiscal policy are inextricably intertwined. At the heart of this thinking sits the idea of a government’s budget constraint. If government spending stimulates demand to the extent of driving up inflation, and monetary policymakers then respond by raising interest rates, a nasty surprise can ensue.

Higher interest rates increase a government’s interest payments on its debt. If the government responds by issuing even more debt to finance its activities, it can make inflation rise even faster – as the government’s extra spending would end up driving up demand just as the central bank is trying to curb it. In other words, a government can only run so much of a deficit before unforeseen problems crop up.

Today this lesson is even more relevant than Sargent and Wallace could have imagined. Nowadays, interest rates can no longer be a central bank’s first instrument of monetary policy: public and private debt are so high that raising rates could potentially make repayments unmanageable for many.

To take the US as the most prominent example, the Fed would instead start out by cutting back the level of government bond purchases going on to its balance sheet. This bond purchasing has ballooned in the past decade, particularly since governments’ heavy deficit spending during the pandemic.

The problem is that the money created through QE ends up, for reasons that don’t need to be explained here, in the reserves of commercial banks held by the central bank. In the US, these sums now approach a fifth of all of the Fed’s assets.

As and when the Fed decides to “taper” QE – now running at US$120 billion (£85 billion) of purchases per month – as a first step in tightening policy to lean against inflation, this will result in a lower proportion of banks’ assets being lodged with the Fed in the form of reserves, and increase the scope for banks to lend to the real economy.

Such credit expansion and the associated increase in the velocity of money is likely to fuel the inflation pressures that the Fed wants to counter. Since one of the main aims of QE is to increase bank lending, it’s a paradoxical effect – just like the previous example of higher interest rates increasing inflation.

The bottom line is that public debt has expanded to the extent of becoming unaffordable in a free market. Today’s conundrum created by QE is just the latest demonstration of the reality that disregarding government budget constraints will result, by one way or another, in higher inflation.

Long-term trends

The final question is how all of this relates to long-term trends in the labour market and elsewhere. It is often said that in the past couple of decades, globalisation and technology have both helped to reduce inflation. Globalisation has kept wages lower by moving production to poorer countries. Technology has made it cheaper to produce goods and therefore brought prices down, while the the gig economy has reduced the cost of services.

But a recent book by British-based economists Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan argues that the years to come will be far less deflationary, for several reasons. China’s labour market participation is rising, which is increasing wages, and baby boomers are retiring, taking a very large generation out of the labour market and making workers more scarce and therefore more valuable.

It’s a fascinating argument, but still very debatable. For example, possible inflationary effects of ageing populations might yet be outweighed by the deflationary effect of rapid technological change automating more jobs. This will reduce workers’ bargaining power and therefore act as a brake on wage growth. Also, most people consume less in retirement, and certainly do not borrow as much: the ageing of the baby boomers will therefore be another source of deflation.

In sum, there is good reason to expect inflation in the short to medium term, but the longer term picture is more mixed. The seeds of higher long-term inflation are surely present, but the chances of their germinating will depend to a large extent on to what extent the extra fiscal stimulus from the US and elsewhere leads to increased production, as opposed to only consumption.

If there is higher business investment and labour participation, government budget deficits will narrow faster as the private sector gets back into gear and pays more in taxes. This will also help the Fed to find a smoother path through the minefield of the exit from QE, since the increased bank lending will be more likely to be unlocking sustainable economic growth. If so, it is still possible that the central banks’ claims that inflation will only be transitory could still be proven right.

Brigitte Granville, Professor of international economics and economic policy, Queen Mary University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.