Luciano Rispoli, University of Surrey

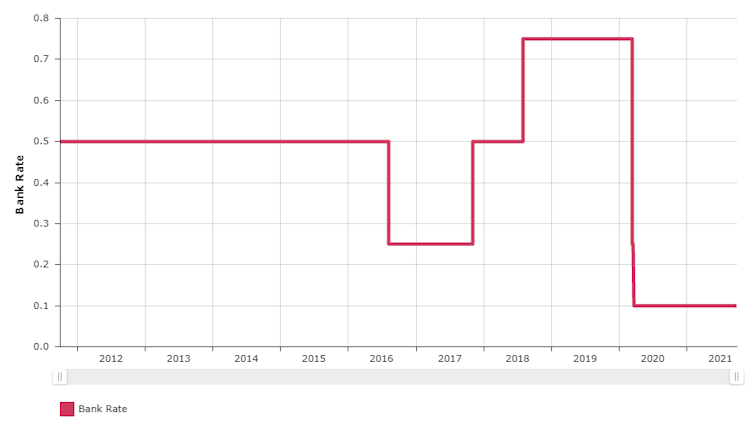

The pandemic has been a bruising experience for the global economy. In response, many countries have kept interest rates low, to keep money moving at a time of extreme uncertainty. In the UK, rates have been at an all time low of 0.1% since March 2020. But this may be about to change.

Andrew Bailey, the governor of the Bank of England, has hinted at an interest rate rise. This would lead to a rise in the cost of borrowing. More expensive borrowing generally means lower levels of disposable income, followed by lower levels of household spending. The lower demand for goods then lowers prices, which leads to a decrease in inflation.

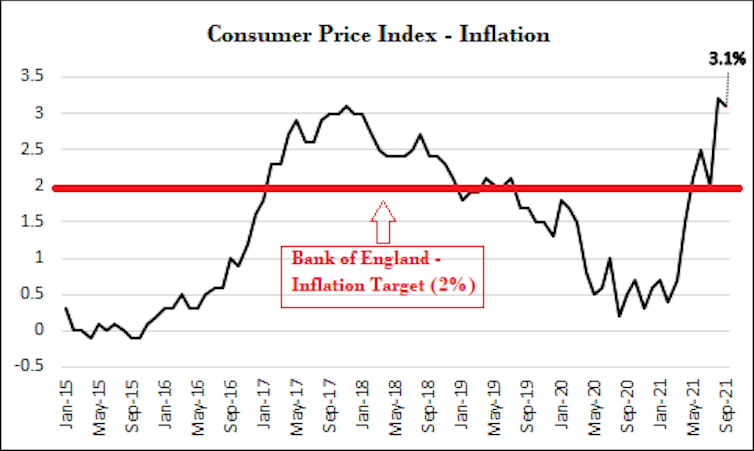

The Bank of England is signalling that curbing inflation may be necessary, given that the annual rate currently stands at 3.1%. Rising prices, without a match in wage increases, adversely affects incomes, reducing the purchasing power of households (especially the poorest). Given that the Bank of England’s main role is to keep inflation at 2%, you can see why Bailey is considering the rate rise.

Typically, though, the Bank of England cuts interest rates during lean periods to get people spending and stimulate the economy. It has historically tended to increase the rate during economic booms, to “cool down” the economy and prevent inflation getting too high.

But almost two years after the arrival of COVID-19, even with some elements of normal life resuming, few would describe the current situation, after lockdowns, business closures and furlough, as economically booming.

The reason that an increase in interest rates now seems likely is that the inflation that we are seeing is unlikely to be as a result of economic growth. Among the facts, the Office for National Statistics calculated that in September 2021 the largest contribution to the inflation rate came from rising costs in transport; housing and household services (the cost of renting or buying, furnishing and maintaining a home); restaurants and hotels; and recreation and culture.

The key challenge for the Bank of England is to identify whether these price rises are temporary or not. Particularly important will be the monitoring of rising energy prices, which the bank predicts could push inflation even higher (to 4%) later in the year.

A banking balancing act

The big question is whether the British economy, which is still in a process of recovery, can afford a higher interest rate. For while recent data has pointed to a better than expected jump in GDP growth, the UK economy reportedly remains 3.3% below pre-pandemic levels.

The recovery seems to have stagnated mainly due to supply chain issues (labour and raw materials shortages), with the recent energy crisis creating even more uncertainty. Despite a jump in current unfilled vacancies to a record 1.1 million, the fact that the furlough scheme was only recently phased out suggests that the labour market might still be weak.

The danger is that interest rates could go up too soon, with a depressing effect on economic activity and the housing market – reaching the desired goal of decreasing inflation but at the expense of economic growth. In the words of one former Bank of England committee member, an interest rate hike now would be a “disaster”.

Bank of England interest rate over time

Overall, then, it is not yet clear whether an interest rate rise is in the economy’s best interest right now. However, the Bank of England policy mandate is clear in that it can’t afford to let inflation go out of control.

For now, we will have to wait while the the bank’s monetary policy committee carefully weighs up the options. But although the final policy outcome is the result of a vote, the governor’s remarks unambiguously point to an imminent interest rate rise – very possibly sooner than some economists (and many households) would like.

Luciano Rispoli, Teaching Fellow in Economics, University of Surrey

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.