Fraser Macdonald, University of Waikato

Only 1.7% of Papua New Guineans have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19. This has been a cause of concern for the international community, who are watching the virus spread through an exposed population with high rates of co-morbidities and minimal access to healthcare.

The mood within the country, however, is very different. No doubt there is abundant fear, but this has centred on the vaccine itself.

Many Papua New Guineans have access to the vaccine, even in some of the remotest corners of the country. They are also fully familiar with injected medicines and vaccinations against diseases like polio and measles.

But millions of Papua New Guineans are not getting vaccinated against COVID because they are terrified of this specific vaccine. This is not “vaccine hesitancy”, but full-blown opposition, a genuine antipathy.

Community vaccine rollouts have been targeted with death threats, attacked by furious crowds, and castigated as a “campaign of terror”.

The recently introduced “no jab, no job” policy, meanwhile, has met with lawsuits, mass resignations and the fraudulent acquisition of vaccination certificates to circumvent the dreaded vaccine.

So, why is there such a fierce resistance to the COVID vaccine? The key difference, as any good anthropologist will tell you, is cultural context.

Spiritual sickness

Any attempt to understand local views on the COVID vaccine must first appreciate that, within Melanesian societies, physicality is intimately connected to morality and spirituality. Because of this, biomedical explanations for disease are usually secondary to other causes or irrelevant.

This is mainly due to the small, sometimes non-existent role played by government education in the lives of most Papua New Guineans, especially the roughly 80% that live in rural villages.

For example, should an otherwise healthy person suddenly become ill and die, sorcery or witchcraft may be deemed the cause. Accusations are linked to interpersonal conflicts and jealousies that may have precipitated the mystical assault.

Such interpretations usually occur with individual misfortunes – not much larger events like a global pandemic. This is where Christianity becomes hugely important, making sense of broader problems like this.

The role of Christianity

Nearly all Papua New Guineans (99.2%) are Christian. And the religious landscape in the country is powerfully influenced by Pentecostal and evangelical churches.

In PNG, Christianity provides not only the promise of eternal salvation, but biblically inscribed frameworks and prophetic ideas that inform how people live and view the world around them.

Many Christians, especially those believing in the Pentecostal and evangelical traditions, have a strong interest in the end of the world, as this signals the return of Jesus Christ.

Crucially, the imminent return of Christ is heralded by the world’s rapid moral decline and humanity being branded with the mark of the beast — a process mandated by Satan. As such, many Papua New Guinea Christians continuously and fearfully scan the horizon for this definitive sign.

Years ago, some Papua New Guinean friends declared barcodes were the mark. More recently, they insisted it was the government’s national ID card initiative. Now, in a completely different order of magnitude and intensity, it is the COVID vaccine.

As one group protesting a vaccine drive recently chanted, “Karim 666 chip goh!”, or “Get out of here with Satan’s microchip”.

From this perspective, the vaccine is a vehicle for much larger forces of global and cosmic tyranny. The speed with which the vaccine was developed, its global reach, and the apparent coercion of vaccine mandates all further strengthen suspicions of its evil origins.

However, Christianity is not the sole factor spurring anti-vaccination sentiment. Indeed, powerful misinformation on social media has also been influential, such as rumours the vaccine carries a microchip or commonly causes death. People also have a well-founded distrust of outsiders, and they view both the virus and vaccine as foreign assaults on PNG’s sovereignty.

In the absence of Western biomedical knowledge or a lack of faith in its validity, these theories flourish. Those with more sustained exposure to Western culture often try in vain to convince their compatriots against this kind of thinking.

Alternative treatments

While defiantly resisting vaccination, many Papua New Guineans nonetheless acknowledge COVID-19 is real and that it causes sickness.

With infection rates, hospital admissions, and deaths now surging, it would be hard to ignore this reality. The rising COVID-19 mortality across the country has scared some into receiving the vaccine, but even those open to vaccination are easily spooked by rumours of subsequent death.

In the absence of vaccinations, Papua New Guineans have turned to three main methods of treatment: prayer and healing, organic remedies, and reliance on a claimed strong natural immunity to disease.

As Christians strongly influenced by the evangelical and Pentecostal traditions, many people pray to God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit to not just mitigate, but annihilate, the evil sickness.

In addition, many are turning to organic traditional remedies to ward off illness. This mainly consists of spices and leaves used in drinks and steaming.

Finally, there is a strongly held belief that Papua New Guineans possess an intrinsically strong immune system, buttressed by a diet of garden food, which makes them more resistant to the incursion of the COVID virus.

What can the authorities do?

For most westerners, vaccines are an obvious and intrinsic good. For many Papua New Guineans, vaccines are a dangerous, unknown, and sinister threat. This is due to a combination of forces – governmental neglect, strong religiosity, and a justified distrust of outsiders.

This local position needs to be very sensitively understood and respected, not dismissed or criticised.

At the same time, deaths must be prevented and the thick fog of opposition surrounding the vaccine must be dissipated. But how?

Detailed information about the vaccine, including its creation, contents, efficacy, and potential side effects, must be made fully known to people before asking them to be vaccinated. Insisting a population with minimal information be vaccinated is not ethical or fair.

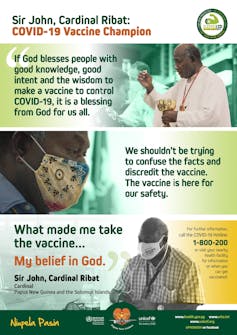

Likely in response to the widespread apocalyptic interpretations of the vaccine, the PNG Council of Churches is now actively promoting its safety and benefits. The government also needs to step up its efforts and commit to a nationwide educational campaign if hopes for substantial vaccine uptake are ever to be realised.

The success of the whole endeavour – and steering Papua New Guinea away from a public health catastrophe – will likely turn on persuading ordinary people the vaccine is a divine blessing and not a Satanic curse.

Fraser Macdonald, Senior Lecturer in Anthropology, University of Waikato

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.