Patrick White, James Cook University and Claire Brennan, James Cook University

Australia’s local governments breathed new life into embattled regional communities after the second world war. Today, this history reminds us of the role local councils and communities should play in plans to power the national recovery from the COVID-19 shutdown.

Australia’s experience of this pandemic has opened a door to the past. The Spanish flu pandemic led to emergency powers, border closures and authority contests between state and federal governments.

Now, as Australia reopens the economy, it is time to consider lessons from post-war reconstruction. It was one of the nation’s greatest achievements. Post-war reconstruction reshaped the economy and set a national agenda for the following decades.

But, in the broad memory of the period, local initiatives are often overlooked. Responses in North Queensland, for instance, proved reconstruction was not the exclusive preserve of state and federal governments.

The social and economic impacts of the war had devastated North Queensland’s isolated communities. They faced an uncertain future. Without robust connections to national authorities, the people of North Queensland were at risk of being left behind by centrally planned reconstruction programs.

In response, the region’s local governments mobilised their collective resources. They led a huge recovery program, which transformed North Queensland. The efforts of councils and their communities helped stimulate a period of record northern development.

Planning began early

Post-war planning began long before hostilities ended. Under pressure from the federal Labor opposition, Prime Minister Robert Menzies had established a small Reconstruction Division in 1940. A political crisis consumed the leadership of both Menzies and his deputy, Arthur Fadden, and Labor’s John Curtin became prime minister in 1941.

Preoccupied with the war effort, Curtin at first overlooked reconstruction. Internal party pressure soon stimulated a national agenda and the creation of the Department of Post-War Reconstruction. It began work in 1942 with Ben Chifley as minister.

Herbert “Nugget” Coombs was one of the architects of reconstruction. He reckoned the war had provided the nation with an:

opportunity to move consciously and intelligently towards a new economic and social system.

COVID-19 provides similar opportunities for a centrally planned reboot of the national economy. Perhaps, as with the post-war reconstruction of North Queensland, local innovation could then drive this recovery.

Regional alliance set agenda

From 1942, preparations for the war in the Pacific transformed North Queensland. Huge numbers of Allied troops descended on the region. This led to shortages of food, jobs and housing.

Being close to the conflict zones in New Guinea and the Coral Sea intensified fears of invasion. Local residents were frustrated by a lack of attention from distant state and federal governments.

In 1943, one local council chairman said:

Councils should be given a greater share in the responsibility of good government of the people in their areas. The tendency [in Australia] is to govern from capital cities, and no matter how sympathetic the Governments may be it often results in control by persons not fully acquainted with local needs.

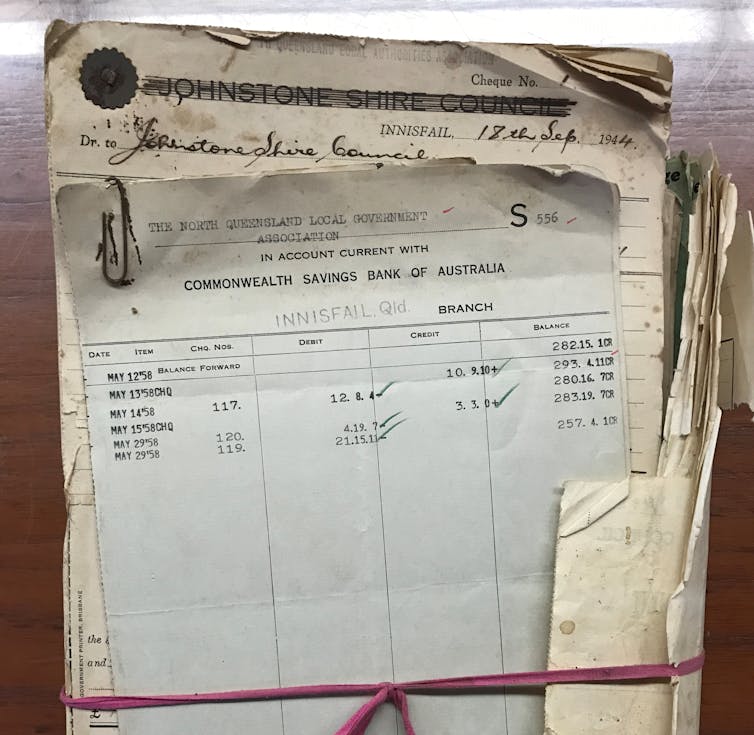

Local governments seized the initiative. Across a territory similar in size to the area from Sydney to the Gold Coast and west to Tamworth, North Queensland councils formed an ambitious alliance. They created the North Queensland Local Government Association in 1944.

The association aimed to overcome political and parochial rivalries. It formed bipartisan committees that examined regional priorities and developed a “Northern Reconstruction” agenda.

The projects the association sponsored resonate with the present challenges flowing from COVID-19. Increased civic engagement helped to deliver transport projects and industrial development. Local governments formed partnerships with power companies, port authorities and chambers of commerce.

Local governments fostered better connections across the region and with the rest of Australia. The association became a conduit for the flow of local knowledge to state and federal authorities. This helped focus crucial national resources on regional problems.

Northern reconstruction left visible monuments: a massive steel bridge over the Burdekin River, the Tully Falls hydro scheme and better road and rail networks. Less visible outcomes included resources for local schools, tourism development and better responses to natural disasters.

The association even had a commitment to intellectual endeavour. It sponsored a young historian, Geoffrey Bolton, to write the region’s first scholarly history.

Regions hard hit again

The global pandemic is not over. We still face the danger of further clusters of infections, a second wave is possible, and more deaths are likely. The shock waves from job losses, social disruption and isolation continue to spread more widely than the virus itself.

The nation’s regions have experienced this pandemic differently from metropolitan areas. In northern Australia, the impacts from disruption to tourism and other local economic sectors threaten to be devastating. In Western Australia, local networks have already proven invaluable.

Across regional Australia, the historical example of “Northern Reconstruction” shows the capacity of local governments to lead disaster recovery.

Patrick White, PhD Candidate in History and Politics, James Cook University and Claire Brennan, Lecturer in History, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.