Penny Venetis, Rutgers University Newark

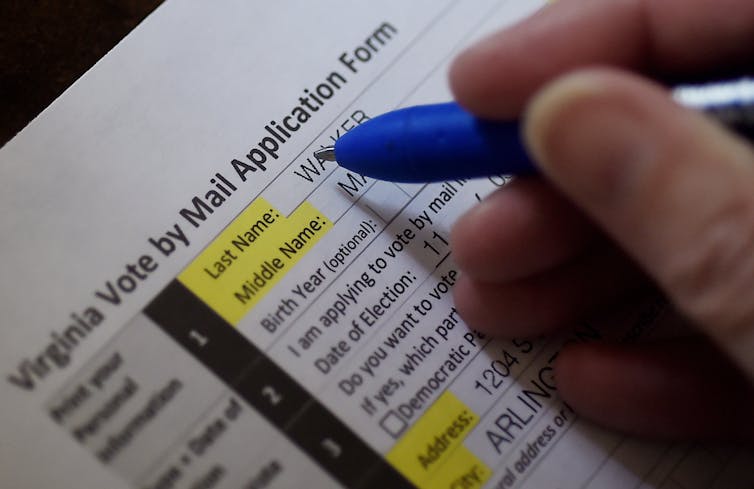

The Trump campaign and the Republican National Committee filed lawsuits recently against New Jersey and Nevada to prevent expansive vote-by-mail efforts in those states.

These high-profile lawsuits make the same argument that Republicans have made in many lesser-known lawsuits that were filed around the country during the primary season. In all of these lawsuits, Republicans argue that voting by mail perpetuates fraud – an argument President Donald Trump makes daily, on various media platforms.

Yet, study after study has shown that there is no basis for these claims. Indeed, the opposite is true – voting by mail is rarely subject to fraud. Twitter has even slapped warnings on President Trump’s tweets that link vote-by-mail to voter fraud, because they perpetuate false information.

Courts, for the most part, have sided with Republicans, and in some cases even adopted the unsubstantiated fraud assertions. The effect of these rulings has been that Americans had to vote in person during the global pandemic, risking their lives. By filing these lawsuits, Republicans are forcing voters to choose between being safe and exercising their fundamental right to vote in November.

Suits span the country

Here is a representative sample of these lawsuits:

• In April, when public health officials were not entirely sure how COVID-19 spread, and stay-at-home orders were in place throughout the country, the Republican-led Wisconsin legislature sued to stop Democratic Governor Tony Evers’ executive order extending voting-by-mail deadlines for the primary election. Wisconsin’s Supreme Court sided with the Republicans.

• That victory was not enough. In a parallel suit, Wisconsin Republicans secured an opinion from the U.S. Supreme Court, which held that all mail-in ballots had to be postmarked by primary election day. Dissenting, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg stated: “The Court’s order, I fear, will result in massive disenfranchisement.”

• In Texas, Republican Attorney General Ken Paxton argued in multiple lawsuits that voting by mail should be available only to actual COVID-19 victims, and not to voters who feared being infected at polling sites. After initially losing in court, Paxton publicly threatened, in writing, to arrest and prosecute any election official who distributed information about voting by mail. This left election officials in a quandary because Paxton’s threat conflicted with a state court order that expanded Texas’s vote-by-mail measures to all voters.

A federal trial court called Paxton’s threats “voter intimidation.” Undaunted, Paxton successfully appealed both the federal and state court decisions that ruled against him. Both the Texas Supreme Court and the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals sided with Paxton though, and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear appeals of those cases, allowing those judgments to stand.

In ruling for the Republicans, the Texas Supreme Court stated: “For the population overall, contracting COVID-19 in general is highly improbable” and that “a lack of immunity alone could not be a likely cause of injury to health from voting in person.”

But, by July 9, primary day, Texas was in the grips of a massive COVID-19 crisis. For each of the 10 days preceding the primary election, there were record numbers of COVID-19-related hospitalizations in the state. Houston hospitals were in danger of running out of hospital beds. Republican Gov. Greg Abbott urged everyone to stay home unless it was an emergency, and issued executive orders reclosing the state. While the pandemic raged around them, Texas voters had to vote in person.

• In Missouri, lawsuits by advocacy groups, including the NAACP, sought to expand vote by mail efforts. A state court sided with Republican officials who vigorously opposed the suit and held that “fear of illness” does not qualify as a reason to receive a mail-in ballot.

• In Iowa, after a successful vote-by-mail primary on June 2, the Republican legislature tried to prevent the Iowa Secretary of State from running future elections using mail-in ballots. This was not a lawsuit, but mirrors many of the legal actions mounted by the GOP across the country. In response, a bipartisan group of local election officials sent a letter to the legislature, stating: “The 2020 primary was very successful, based on a variety of metrics largely due to the steps taken by the Secretary. Counties experienced record or near-record turnout. Election Day went very smoothly. Results were rapidly available. Why would the state want to cripple the process that led to such success?”

Falsehoods become law

Several of the courts discussed above have nonetheless embraced the idea that mail-in voting leads to fraud.

For example, in the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which sanctioned the Texas Republicans’ opposition to voting by mail, Judge James C. Ho wrote a gratuitous supplemental concurring opinion, focusing solely on mail-in ballot fraud. Similarly, the Missouri trial court that refused to expand the pool of voters who could vote by mail discussed voter fraud at length, to justify its decision.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Without providing any explanation or evidence to the contrary, these decisions essentially erase scientific findings, cementing into law unsubstantiated and discredited claims linking voting by mail to fraud. This gives these faulty legal decisions tremendous power to impact how Americans vote this November, regardless of the strength of the COVID-19 virus.

Judges who preside over newly filed Republican National Committee and Trump campaign lawsuits will undoubtedly look to those opinions because of the similarity in claims. While those decisions do not have to be followed to the letter in New Jersey and Nevada, they still represent a body of law that judges will need to consider. Even flawed judicial opinions have the power to shape the future.

Penny Venetis, Clinical Professor of Law, Director of the International Human Rights Clinic, Rutgers University Newark

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.