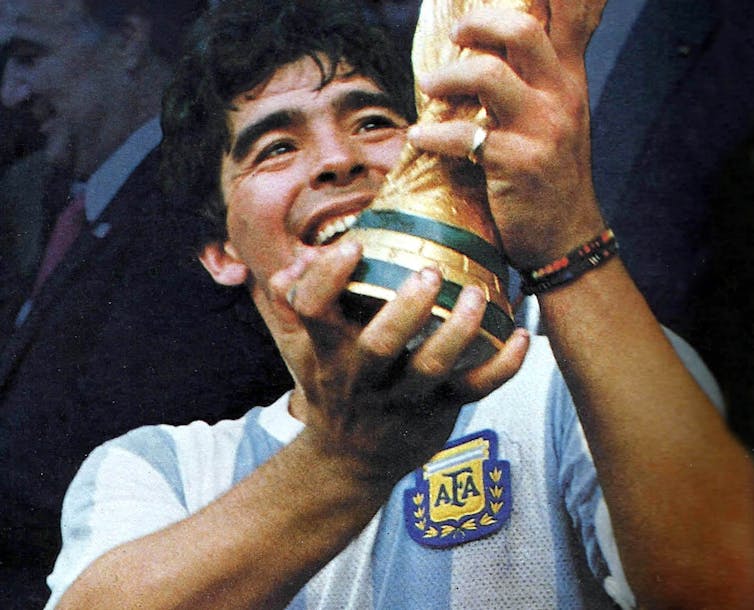

The greatest player in the history of the game Photo by Guillaume de Germain on Unsplash

Matthew Brown, University of Bristol

The death of the greatest player in the history of the game of Association Football, Diego Armando Maradona, on 25 November produced an outpouring of grief and nostalgia around the world. He was such an important figure in his native Argentina that the president declared three days of mourning.

In England, though many have praised his skill and achievements, his death has provided the opportunity to dig up the old humbug about the Hand of God goal at the 1986 World Cup, which involved Maradona’s fist essentially knocking the ball into England’s goal. For some, even in death, Maradona was still the cheat who could not be forgiven. Yet, it was precisely his refusal to recognise the presumed superiority of the Englishmen flailing before him that gave joy to millions worldwide.

The inability of a few in England to move on from that goal speaks to the historical processes that underpin Britain’s relationship with Latin America, which in my research I have characterised as a combination of “culture, capital and commerce that formed an informal empire” from the mid-19th to the early 20th century.

The problem is that “football was created in England, but perfected in South America”, as the historian Brenda Elsey has written.

We saw this when Peru’s Teófilo Cubillas punctured Scottish dreams in 1978 and in Maradona’s performance in 1986. Then there was Brazilian Ronaldinho’s lob that left English goalkeeper David Seaman questioning gravity and the universe itself at the 2002 World Cup. Britain’s relationships with South America have been defined more by football than by anything else.

The Hand of God goal and “Goal of the Century,” which came minutes later in the same game, brought joy and spiritual uplift to so many people in Latin America. It represented a “cosmic” rupture in the universal order of things (to quote the classic commentary on the match by Victor Hugo Morales) which up-ended English assumptions of superiority that had been accepted by some elites across the continent. This was particularly the case in Argentina, where English-speaking communities had reached into the hundreds of thousands by the 1980s.

The depth of feeling that accompanies Maradona’s death speaks to the abiding sense that he was somehow responsible for a moment that has acquired spiritual meaning for the way it broke historical patterns.

In his autobiography Yo Soy El Diego (I Am The Diego), Maradona reflected on the World Cup victory over England, which happened in the wake of the war over the Falklands/Malvinas.

Somehow we blamed the English players for everything that had happened, for everything that the Argentinian people had suffered. I know that it sounds crazy but that’s the way we felt. The feeling was stronger than us: we were defending our flag, the dead kids, the survivors.

Sport, in these terms, had become a surrogate for warfare, an opportunity for the defeated to inflict pain on the victors through whatever means possible. In addition to the Malvinas/Falklands conflict, this sentiment was shaped by the strong British influence on Argentinian economic and cultural life.

Argentinian nationalism was marked in different ways by the British construction of the railways, as well as the 1890s Baring Bank crisis that nearly bankrupted Argentina and left Britain relatively unscathed. There was also the Harrods luxury shop in Buenos Aires, the polo clubs and the substantial British community in the city and in the pampas (fertile flatlands surrounding Buenos Aires).

In England, the continuing anger that Maradona “got away with it” comes out of the ashes of empire. With historical perspective, we can see the British refusal to relinquish the Falklands/Malvinas in 1982 in its refusal to accept the loss of the match, and subsequently, as part of a reluctance to step back from two centuries of imperial engagement with Latin America.

As many have noted since Maradona’s death, he left a trail of destruction in his wake. He can be seen as a victim of some of the people who surrounded him, as well as the maker of much of that destruction. The drugs, revolutionary politics, domestic abuse and emotional outbursts, which are the most visible parts of the media narrative, fit snugly into the British stereotype of the combustible Latin American firebrand.

Yet as Argentinian scholars like Eduardo Archetti and Pablo Alabarces pointed out, football and masculinity were wrapped up together over a century ago. This combination makes Maradona the stand-out figure of a football culture that gloried in the humiliation of the opponent. It saw defeat as a result of feminine weakness while also marvelling at the artistic beauty of the footballer’s body in flight and the perfect arc of the ball as it nestled into the top corner.

As the writer Ayelén Pujol has observed, Maradona’s achievements and his rebellions were an inspiration to millions of marginalized citizens; including the women footballers who today strive to transform the football establishment in their own ways.

With the current prohibition of fans in stadiums due to coronavirus, we are ever more anxious for legends and heroes who will unite us. We long for community and public spaces where we can share moments of joy and sadness together. Diego Maradona was central to many of those moments in the past, and his life will remain a key reference point in the history of the world as a result.

Matthew Brown, Professor in Latin American History, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.