Natasha Blaize Gardiner, University of Canterbury and Cassandra Brooks, University of Colorado Boulder

Two-thirds of the world’s oceans fall outside national jurisdictions – they belong to no one and everyone.

These international waters, known as the high seas, harbour a plethora of natural resources and millions of unique marine species.

But they are being damaged irretrievably. Research shows unsustainable fisheries are one of the greatest threats to marine biodiversity in the high seas.

According to a 2019 global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services, 66% of the world’s oceans are experiencing detrimental and increasing cumulative impacts from human activities.

In the high seas, human activities are regulated by a patchwork of international legal agreements under the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). But this piecemeal approach is failing to safeguard the ecosystems we depend on.

Empty pledges

A decade ago, world leaders updated an earlier pledge to establish a network of marine protected areas (MPAs) with a mandate to protect 10% of the world’s oceans by 2020.

But MPAs cover only 7.66% of the ocean across the globe. Most protected sites are in national waters where it’s easy to implement and manage protection under the provision of a single country.

In the more remote areas of the high seas, only 1.18% of marine ecosystems have been gifted sanctuary.

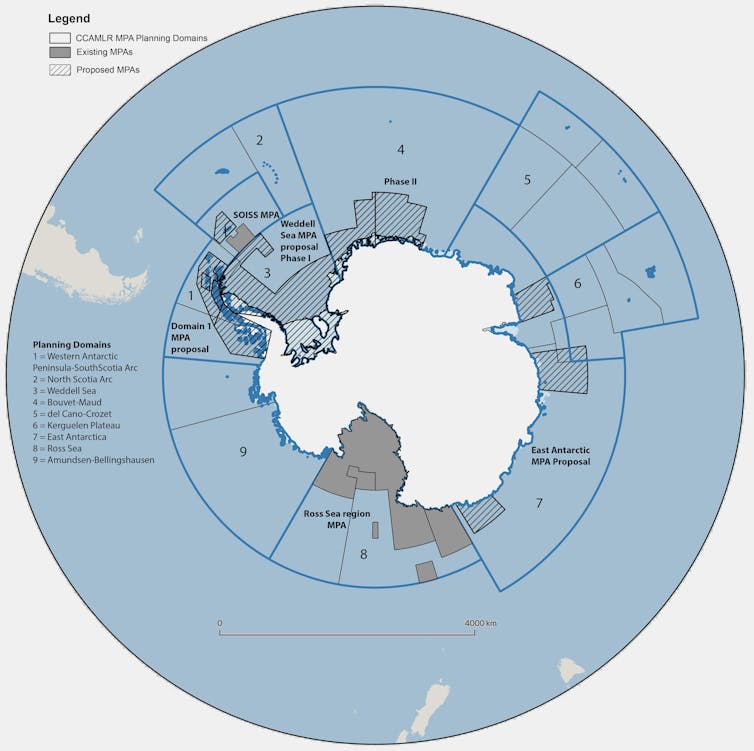

The Southern Ocean accounts for a large portion of this meagre percentage, hosting two MPAs. The South Orkney Islands southern shelf MPA covers 94,000 square kilometres, while the Ross Sea region MPA stretches across more than 2 million square kilometres, making it the largest in the world.

The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) is responsible for this achievement. Unlike other international fisheries management bodies, the commission’s legal convention allows for the closing of marine areas for conservation purposes.

A comparable mandate for MPAs in other areas of the high seas has been nowhere in sight — until now.

A new ocean treaty

In 2017, the UN started negotiations towards a new comprehensive international treaty for the high seas. The treaty aims to improve the conservation and sustainable use of marine organisms in areas beyond national jurisdiction. It would also implement a global legal mechanism to establish MPAs in international waters.

This innovative international agreement provides an opportunity to work across institutional boundaries towards comprehensive high seas governance and protection. It is crucial to use lessons drawn from existing high seas marine protection initiatives, such as those in the Southern Ocean, to inform the treaty’s development.

The final round of treaty negotiations is pending, delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, and significant detail within the treaty’s draft text remains undeveloped and open for further debate.

Lessons from Southern Ocean management

CCAMLR comprises 26 member states (including the European Union) and meets annually to make conservation-based decisions by unanimous consensus. In 2002, the commission committed to establishing a representative network of MPAs in Antarctica in alignment with globally agreed targets for the world’s oceans.

The two established MPAs in the high seas are far from an ecologically representative network of protection. In October 2020, the commission continued negotiations for three additional MPAs, which would meet the 10% target for the Southern Ocean, if agreed.

But not a single proposal was agreed. For one of the proposals, the East Antarctic MPA, this marks the eighth year of failed negotiations.

Fisheries interests from a select few nations, combined with complex geopolitics, are thwarting progress towards marine protection in the Antarctic.

CCAMLR’s progress towards its commitment for a representative MPA network may have ground to a halt, but the commission has gained invaluable knowledge about the challenges in establishing MPAs in international waters. CCAMLR has demonstrated that with an effective convention and legal framework, MPAs in the high seas are possible.

The commission understands the extent to which robust scientific information must inform MPA proposals and how to navigate inevitable trade-offs between conservation and economic interests. Such knowledge is important for the UN treaty process.

As the high seas treaty moves closer to adoption, it stands to outpace the commission regarding progress towards improved marine conservation. Already, researchers have identified high-priority areas for protection in the high seas, including in Antarctica.

Many species cross the Southern Ocean boundary into other regions. This makes it even more important for CCAMLR to integrate its management across regional fisheries organisations – and the new treaty could facilitate this engagement.

But the window of time is closing with only one round of negotiation left for the UN treaty. Research tells us Antarctic decision-makers need to use the opportunity to ensure the treaty supports marine protection commitments.

Stronger Antarctic leadership is urgently needed to safeguard the Southern Ocean — and beyond.

Natasha Blaize Gardiner, PhD Candidate, University of Canterbury and Cassandra Brooks, Assistant Professor Environmental Studies, University of Colorado Boulder

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.