Clare Wright, La Trobe University

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images and names of deceased people.

In May 2020, the international mining giant Rio Tinto made a calculated and informed decision to drill 382 blast holes in an area of its Brockman 4 mining lease that encompassed the ancient rock shelter formations at Juukan Gorge in Western Australia’s Pilbara region.

In a matter of minutes, eight million tonnes of ore were ripped from the earth, and with them, 46,000 years of cultural heritage destroyed.

The Puutu Kunti Kurrama Pinikura people, who are the traditional owners of that land, lost their material connection to sacred sites of ceremonial, clan and family life, the basis for their political and social organisation. The Australian people lost a significant chunk of their national estate. For this hefty price we all paid, Rio Tinto lawfully gained access to $135 million dollars of high-grade iron ore.

The Human Rights Law Centre said that the global Corporate Human Rights Benchmark, based in the Netherlands, should strip Rio Tinto of its status as a global human rights leader. Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who three years earlier had lovingly cradled a lump of coal in his hands in parliament, said nothing.

In the devastating wake of Juukan, it is timely to ask: can the extractive frontier be just as important as the military frontline in defining the story of our nation?

Nothing new under the sun

One day, all Australian primary school students might learn about the Juukan Gorge the way generations have studied the 19th-century Victorian goldrush, with its own explosive crescendo, the Eureka Stockade.

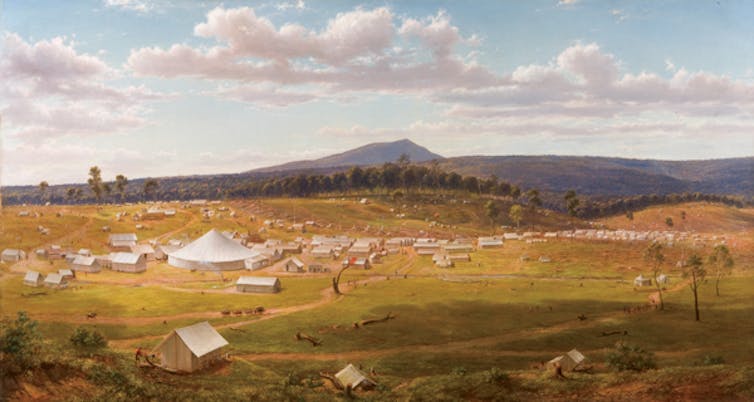

To recap: gold was “discovered” in Ballarat in 1851, when the population of Victoria was about 25,000. By 1861, after a tidal wave of immigration from across the globe, that number had risen to over 600,000. Escaping old-world hierarchies, inequality and poverty, polyglot schemers and dreamers dug their way towards a new life of freedom and independence.

When the British rights and liberties of these cosmopolitan miners were threatened by an authoritarian administration and unjust taxation, the disenfranchised diggers rebelled, leading to a short battle and a long legacy: Eureka became known as “the birthplace of Australian democracy”. Recent research, including my own, has demonstrated that women as well as men participated in this mining boom and its economic and political, if not mythological, inheritance.

Similarly little recognised is the fact that the central Victorian goldrush occurred on the lands of the Wathawurrung people, who had made the fertile hunting grounds of the Ballarat basin their ancestral home for tens of thousands of years.

It is estimated that prior to European contact there were up to 3,240 members of the 25 Wathawurrung language groups. By 1861, 255 Aboriginals remained in the Ballarat region.

As historian Fred Cahir has shown in his landmark book Black Gold, some goldseekers were aware of the extensive quarrying, and subsequent commercial transactions, being carried out by Victoria’s Indigenous inhabitants prior to and after British colonisation. Indeed, resource extraction was practised by Indigenous people throughout the continent.

Batjala-Quandamooka-Kalkadoon historian Kal Ellwood has traced the principal mining trade routes of pre-colonial Australia, proving that Aboriginals used sophisticated underground and pit mining techniques, as well as post-extraction treatment processes, as part of complex commercial relationships.

Indigenous Australia had its own stories to explain how minerals were created and where they were deposited. The bronzewing pigeon Marnbi, for example, seeded gold at Broken Hill, copper at Cloncurry, sandstone at Mt Isa and opals at Coober Pedy. The Europeans were novel. The activity they undertook was not.

The Indigenous people of central Victoria might have been dispossessed, but they were not diffident. They installed toll booths on bridges, requested bounties on vessels crossing rivers, took food and goods from domiciles, and demanded financial restitution for revenue extracted from the land, all as a matter of cultural and legal entitlement stemming from prior ownership: “indefeasible title from time immemorial”, as Wathawurrung elder King Jerry put it to the Geelong Council. (Common law title, as we might call it post-Mabo.)

Such insistence, however, fell on deaf ears. In June 1860, by which time the tent city of Ballarat had been replaced by houses, churches and schools, the Victorian government established a system of six reserves to control and administer the affairs of Aboriginal people.

The other Peninsula campaign

For most Australians, the phrase “the Peninsula campaign” conjures the distant shores of Gallipoli, where ANZACs fought against an alien enemy, apparently for our freedom.

But another battle waged much closer to home — indeed at home — was also referred to as “the Peninsula campaign”. This contest for territorial control occurred on the Gove Peninsula, on the north-east tip of Arnhem Land. The contest was over access to land that contained some of the richest bauxite reserves in the world. It played out over a decade from the late 1950s. The critical year of the campaign was 1963.

The Minister for Territories in the Menzies government, Paul Hasluck, commanded the forces of expansion and development of the Top End; the Yolngu people of the Yirrkala region were the defenders of land that had been legally reserved for them in 1931, and to which they claimed ownership in perpetuity.

The Yirrkala Bark Petitions (August 1963) and the subsequent Select Committee on Grievances of Yirrkala Aborigines (October 1963) were key battles in the offensive. Depending on your perspective, the creation of the mining town of Nhulunbuy, built in 1972, was either the spoils of victory or the price of defeat in the Peninsula campaign.

The military metaphors are mine, not germane to the mining vernacular. I’ve deliberately deployed them here to highlight how much of our national historical consciousness is built around war stories. We understand the language of conflict in binary, adversarial terms: enemy and ally; victor and vanquished.

In reality, the story of how resource extraction led to a four-cornered contest over the right to define and control the narrative of nation-building in north-east Arnhem Land is more complex — and compelling.

Insulating Arnhem Land

The Arnhem Land Aboriginal Reserve, some 80,000 square miles of flat ironstone and low-lying stringybark forest, was established in 1931 with the intention of “insulating” the region’s Aboriginal population from the rest of the Northern Territory. Arnhem Land became “exclusively Aboriginal”; only missionaries, NT welfare officers and Yolngu were allowed in.

Fierce and co-ordinated Yolngu resistance, coinciding with drought, repelled pastoralists in the 1880s and early 20th century. It was not the first time that strangers had come to Arnhem Land. The Yolngu people are considered exceptional because they are the first Australian Aboriginals to have had contact with foreign visitors.

For at least 500 years, Yolngu engaged in seasonal trading visits with the Macassans, Indonesian seafarers who came to exploit the trepang beds of the north-east coast in exchange for tobacco, pottery, knives and cloth.

By the time the European visitors arrived overland, Yolngu had experienced centuries of adaptation to new material culture and notions of labour and trade for goods and services. They understood and engaged in economic and political relationships, both inter-tribally and internationally.

The next strangers to arrive were the missionaries who established bases at Roper River in 1908, Goulburn Island in 1916 and Milingimbi Island in 1923. Following violent encounters with Japanese pearlers and Darwin-based police, a Methodist mission was established at Yirrkala in 1935 to provide sanctuary for the more than dozen clans of Yolngu people of this Miwatj region.

Yirrkala, and surrounding Melville Bay, encompassed the traditional lands of the Gumatj and Rirritjingu clans. Yolngu, having long understood the positive use to which outsiders could be put, accepted the newcomers. The Methodists also accepted most cultural beliefs, permitted language and rituals, employed a philosophy of bilateral learning and, in many cases, developed genuine friendships and important alliances.

Prospecting

The first known geological reconnaissance at Gove occurred in 1952, fewer than two decades after the Yirrkala Mission was established, when Hasluck announced a change of policy, opening the NT’s Aboriginal reserves to mineral prospecting.

The time had come, Hasluck argued, to “extract the latent mineral wealth of the Territory”.

In 1958, the Commonwealth Aluminium Corporation (Comalco) was issued Special Mining Lease No. 1 to prospect 21 square metres of land on Melville Bay, abutting the Yirrkala Mission.

According to Hasluck, times had changed since the 1930s, when the system of Aboriginal land reserves had been established “liberally but rather carelessly”. Now, incentivised by the discovery that a blanket of bauxite lined the Gove Peninsula, Hasluck underscored ‘the necessity for developing our national resources’.

By the wet season of 1962, when the Reverend Edgar Wells took over as superintendent of the Yirrkala Mission, it had become commonplace to see prospectors “walk about the country, boring holes, marking off areas, and finally erecting buildings” without, according to Wells, “any attempt at explanation”. The miners, observed Wells, roamed around “with a renewed assurance … in complete optimism … masters of the future.

On 18 February 1963, the federal government ratified an agreement with Nabalco, a joint Swiss–Australian venture, to mine for bauxite. This meeting took place at the Methodist Overseas Mission’s headquarters in Sydney, attended by mining representatives but no Yolngu.

In May 1963, Rirritjingu elder Mawalan Marika put aside tribal rivalries to join with Mungurrawuy Yunupingu, senior elder of the Gumatj clan, and write to Hasluck. They requested 40 houses, “so we can exchange to make us level between you and we natives”.

The lack of consultation was the primary insult, not the idea that they might be asked to share their land. To the Yolngu mind, they were not only custodians of the land – caretakers – but also owners, with the capacity to cede territory.

When Hasluck unilaterally excised reserved land, he effectively stole land from people who understood both the spiritual and commercial value of their assets.

Notice of the excision of the Arnhem Land Reserve was published in the Government Gazette in May 1963. Over the next two months, there was a flurry of correspondence between Yirrkala, Darwin, Canberra and Sydney. Federal Labor MP Kim Beazley Sr, along with Labor MP Gordon Bryant (later Minister for Aboriginal Affairs and Minister for the Capital Territory in the Whitlam Government), made the long trek to Yirrkala in July to ascertain the level of distress.

Standing in the newly opened Methodist Church, Beazley contemplated the extraordinary artworks that flanked the altar: large boards painted by Yolngu elders of each clan and moiety, including Mungurrawuy. Edgar Wells’ wife, Ann, who interviewed each of the artists as they painted, recognised these panels were a “statement of land claims”, delineating language borders, natural features, sacred sites and “the disputes that inevitably arise over boundaries”.

On viewing the panels, Beazley suggested the Yolngu present a petition to the parliament in their own vernacular. Before leaving Yirrkala, he furnished the wording of the preamble required of any petition to the House. Yolngu did the rest.

On 14 August, Beazley presented the House of Representatives with what have become known as the Bark Petitions: two versions of the text, one in English and one in Yolngu Matha, pasted onto bark and framed with traditional paintings.

There were eight points, but this is the crux: a protest against “decisions taken without them and against them” that were “never explained to them beforehand, and were kept secret from them”, as well as a plea to “hear the views of the people of Yirrkala before permitting excision of this land”. Nowhere do the petitions suggest that Yolngu are opposed to mining per se. What they requested was a voice.

Though Hasluck rejected the Bark Petitions on the grounds they didn’t represent the true wishes of the community (only a small group of young rabble-rousers), the Select Committee on Grievances of Yirrkala Aborigines was empowered — the first time in Australia’s history that a petition had directly led to a parliamentary enquiry.

It concluded that the Bark Petitions were “an appeal to the House of Representatives for protection”. It made 11 recommendations pertaining to how best to integrate the Yolngu into the inevitable establishment of a large mining town on the Gove Peninsula, while preserving sacred sites.

In 1963, the average Aboriginal life expectancy was 42 years. In 1968, the federal government signed an agreement with Nabalco for a 42-year lease to mine and process bauxite in Gove, conditional upon the construction of an alumina refinery and a township able to accommodate 4,000 mining workers, administrators, service providers and their families.

To Wells, the injustice of “giving away of ancestral territorial privilege of children’s children” was simply ‘beyond comprehension’.

Wells was sacked as superintendent on 11 November 1963. The mining lease for Juukan Gorge was granted in 1964.

‘They tricked us.’

In February 2020, I sat with Galarrwuy Yunupingu at his kitchen table in Gunyangara — the Gumatj homeland on Melville Bay, 15 kilometres from Nhulunbuy, now framed by the rusting carcass of the alumina refinery, mothballed by Rio Tinto in 2013 — and read him the list of recommendations from the Select Committee. How many of these things happened, I asked him? “Bäyaŋu,” he answered: None.

They tricked us. They never gave us anything they promised. I’m afraid I have to come to this conclusion. They asked us but they didn’t listen.

Looking at the foundational moments of Ballarat and Nhulunbuy helps to elucidate patterns and themes that should be central to further exploration of how mining has defined the life of our nation. As Galarrwuy has said elsewhere, land rights are one thing, but ownership means more than a moral prerogative.

“We would like to turn the land into money,” Galarrwuy told a somewhat perplexed progressive audience at the 2013 Garma Festival. “Aborigines have land rights but are still the poorest people on earth.”

Ultimately, the Peninsula campaign was not only about the market value of the mineral resources themselves, but also the moral, legal and civic status conferred on those who would call themselves miners. Those who would bring the future along with their bores and excavators. Those who could drive the nation and the economy forward.

In her University of Melbourne Narrm Oration of 2015, From Hunting to Contracting, Marcia Langton outlined the history of Aboriginal Australians’ economic exclusion from colonial times to the 21st century. Mining, she argued, offered First Nations peoples “a new paradigm devoted to development”.

To Langton, examples of Indigenous wealth creation demonstrate Indigenous engagement with the private sector economy is the “best way to close the gap”. (Indeed, the Gumatj Corporation launched its own 100% Yolngu-owned mining training facility and bauxite operations in 2017.)

Where mining is concerned, however, economic development is not a “new paradigm” that Indigenous Australians have latterly come to accept as part of the logic of late capitalism or “postcolonialism”. Rather, an economic stake in the land is something that has been perennially contemplated and contested in territories that have come to hold commercial importance to white Australia.

What has changed, perhaps, is that mining companies have recognised the “social capital” of collaborative working relationships with Aboriginal “stakeholders”. Whether this new alliance proves to be a reliable means of “livelihood and independence” for Aboriginal communities remains to be seen.

Juukan Gorge represents the pinnacle of the colonial mining project. It fulfils the Four-F rating that is at the heart of Australia’s relationship to land: Find it. Fuck it. Flog it. Forget it. Let’s hope that Juukan stands as the most broken, defective, shattered and superseded point of the hill.

This is an edited extract, republished with permission from GriffithReview71: Remaking the Balance, edited by Ashley Hay.

Clare Wright is currently writing a book about the Bark Petitions, the third instalment of her Democracy Trilogy.

Clare Wright, Professor of History, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.