Geordie Williamson, University of Sydney

Research in mathematics is a deeply imaginative and intuitive process. This might come as a surprise for those who are still recovering from high-school algebra.

What does the world look like at the quantum scale? What shape would our universe take if we were as large as a galaxy? What would it be like to live in six or even 60 dimensions? These are the problems that mathematicians and physicists are grappling with every day.

To find the answers, mathematicians like me try to find patterns that relate complicated mathematical objects by making conjectures (ideas about how those patterns might work), which are promoted to theorems if we can prove they are true. This process relies on our intuition as much as our knowledge.

Over the past few years I’ve been working with experts at artificial intelligence (AI) company DeepMind to find out whether their programs can help with the creative or intuitive aspects of mathematical research. In a new paper published in Nature, we show they can: recent techniques in AI have been essential to the discovery of a new conjecture and a new theorem in two fields called “knot theory” and “representation theory”.

Machine intuition

Where does the intuition of a mathematician come from? One can ask the same question in any field of human endeavour. How does a chess grandmaster know their opponent is in trouble? How does a surfer know where to wait for a wave?

The short answer is we don’t know. Something miraculous seems to happen in the human brain. Moreover, this “miraculous something” takes thousands of hours to develop and is not easily taught.

The past decade has seen computers display the first hints of something like human intuition. The most striking example of this occurred in 2016, in a Go match between DeepMind’s AlphaGo program and Lee Sedol, one of the world’s best players.

AlphaGo won 4–1, and experts observed that some of AlphaGo’s moves displayed human-level intuition. One particular move (“move 37”) is now famous as a new discovery in the game.

How do computers learn?

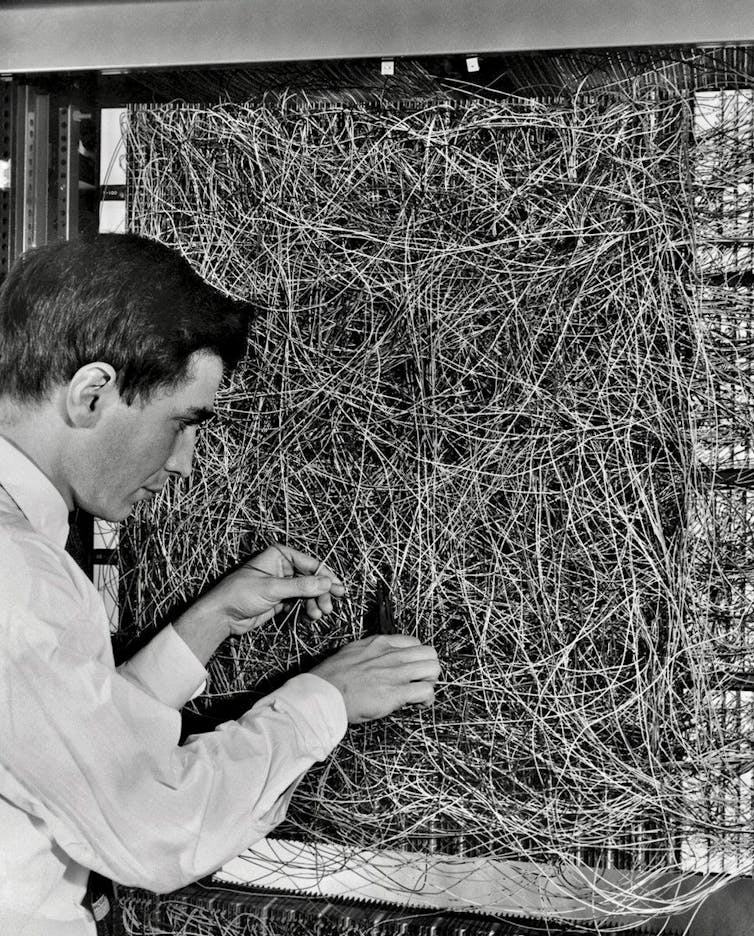

Behind these breakthroughs lies a technique called deep learning. On a computer one builds a neural network – essentially a crude mathematical model of a brain, with many interconnected neurons.

At first, the network’s output is useless. But over time (from hours to even weeks or months), the network is trained, essentially by adjusting the firing rates of the neurons.

Such ideas were tried in the 1970s with unconvincing results. Around 2010, however, a revolution occurred when researchers drastically increased the number of neurons in the model (from hundreds in the 1970s to billions today).

Traditional computer programs struggle with many tasks humans find easy, such as natural language processing (reading and interpreting text), and speech and image recognition.

With the deep learning revolution of the 2010s, computers began performing well on these tasks. AI has essentially brought vision and speech to machines.

Training neural nets requires huge amounts of data. What’s more, trained deep learning models often function as “black boxes”. We know they often give the right answer, but we usually don’t know (and can’t ascertain) why.

A lucky encounter

My involvement with AI began in 2018, when I was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. At the induction ceremony in London I met Demis Hassabis, chief executive of DeepMind.

Over a coffee break we discussed deep learning, and possible applications in mathematics. Could machine learning lead to discoveries in mathematics, like it had in Go?

This fortuitous conversation led to my collaboration with the team at DeepMind.

Mathematicians like myself often use computers to check or perform long computations. However, computers usually cannot help me develop intuition or suggest a possible line of attack. So we asked ourselves: can deep learning help mathematicians build intuition?

With the team from DeepMind, we trained models to predict certain quantities called Kazhdan-Lusztig polynomials, which I have spent most of my mathematical life studying.

In my field we study representations, which you can think of as being like molecules in chemistry. In much the same way that molecules are made of atoms, the make up of representations is governed by Kazhdan-Lusztig polynomials.

Amazingly, the computer was able to predict these Kazhdan-Lusztig polynomials with incredible accuracy. The model seemed to be onto something, but we couldn’t tell what.

However, by “peeking under the hood” of the model, we were able to find a clue which led us to a new conjecture: that Kazhdan-Lusztig polynomials can be distilled from a much simpler object (a mathematical graph).

This conjecture suggests a way forward on a problem that has stumped mathematicians for more than 40 years. Remarkably, for me, the model was providing intuition!

In parallel work with DeepMind, mathematicians Andras Juhasz and Marc Lackenby at the University of Oxford used similar techniques to discover a new theorem in the mathematical field of knot theory. The theorem gives a relation between traits (or “invariants”) of knots that arise from different areas of the mathematical universe.

Our paper reminds us that intelligence is not a single variable, like the result of an IQ test. Intelligence is best thought of as having many dimensions.

My hope is that AI can provide another dimension, deepening our understanding of the mathematical world, as well as the world in which we live.

Geordie Williamson, Professor of Mathematics, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.