Peter Martin, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

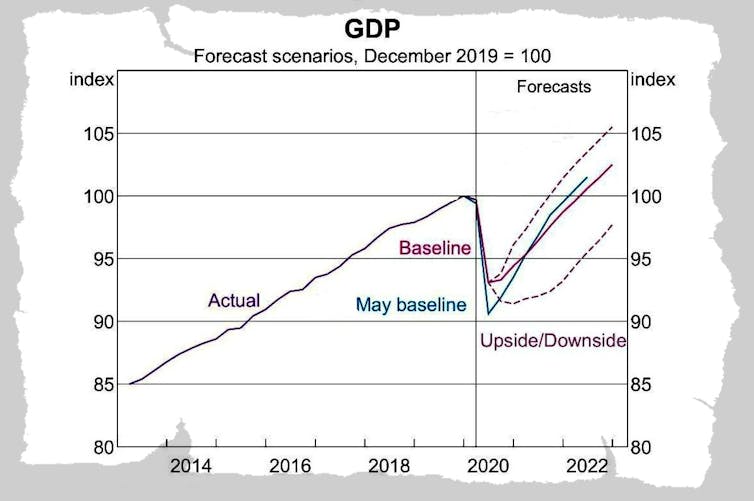

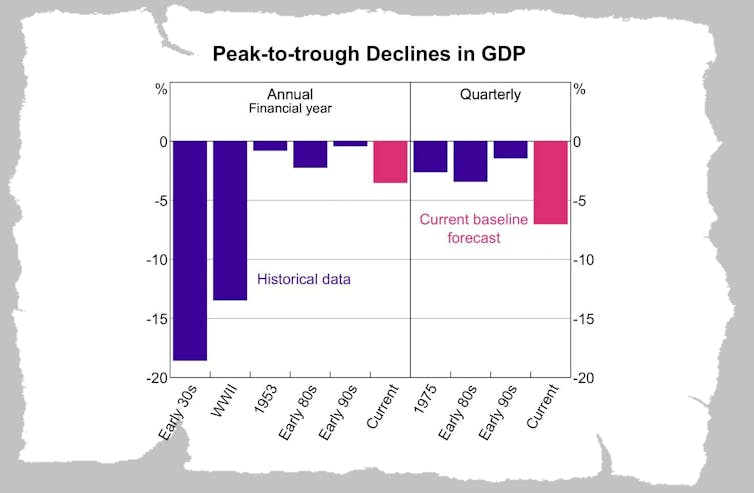

The good news in the Reserve Bank’s latest quarterly set of forecasts is that the recession won’t be as steep as it thought last time.

The bad news is it now expects ultra-weak economic growth to drag on and on, pushing out the recovery and meaning Australia won’t return to the path it was on for years if not the end of the decade.

Its so-called baseline scenario, which is for the worst recession in 70 years, relies on a number of things going right:

the heightened restrictions in Victoria are in place for the announced six weeks and then gradually lifted. In other parts of the country, restrictions continue to be gradually lifted or are only tightened modestly for a limited time, although restrictions on international departures and arrivals are assumed to stay in place until mid 2021

Whereas three months ago in its May update the Reserve Bank expected economic activity to collapse 8% in the year to June 2020 and then bounce back 7% over the following year, it now believes it collapsed a lesser 6% but will claw back only 4% in the year to come.

The direct impact of locked doors and shut shops was smaller than it expected, but the ongoing impacts are “likely to be larger”.

It’ll depend on households

What economic growth there is will be driven by household spending. Business investment, once a key economic driver, won’t be back to anything like where it was until well into 2023.

Business after business has been telling the bank’s liaison officers they have deferred or cancelled planned spending to preserve cash.

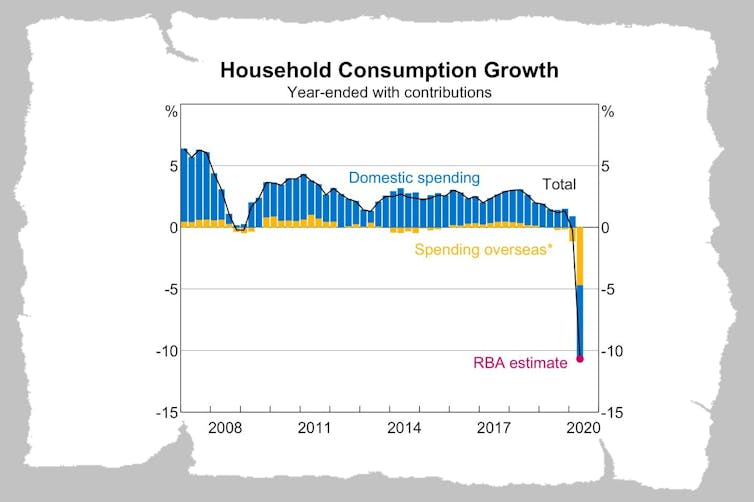

In usual times, household spending accounts for 60% of gross domestic product.

The Reserve Bank believes household spending fell 11% by the middle of the year and will start to edge back up, but it warns that household incomes are expected to slide and unemployment grow as government winds back JobKeeper and JobSeeker:

The JobKeeper program ensures that many more workers remain attached to their job than otherwise. However, it is expected some workers will be retrenched once they are no longer eligible for the subsidy in late 2020 and early 2021. Moreover, the reinstatement of job search requirements for the JobSeeker program outside of Victoria in the September quarter and the lifting of restrictions will result in more people looking for jobs

It will have been heartened by the Prime Minister’s recent decision to make the wind-back of JobKeeper less steep.

The bank says that the way businesses and households adjust to a lower income in the months ahead will be “an important determinant of the outlook over the rest of the forecast period”.

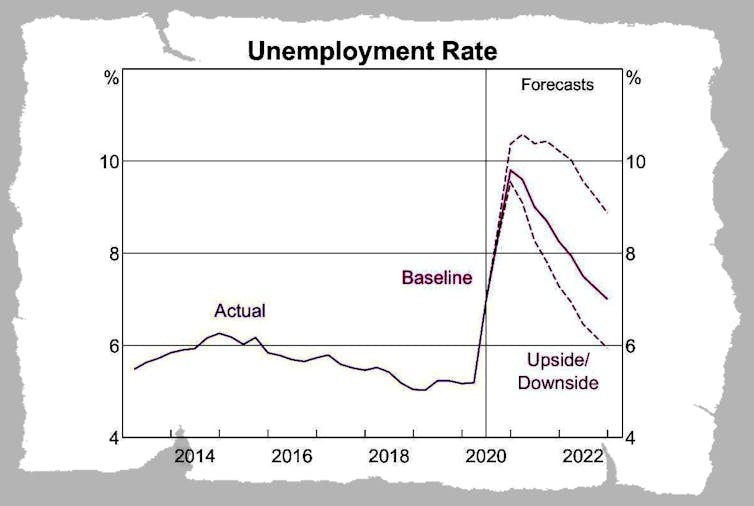

It expects employment to fall further over the rest of the year, as job losses from restrictions in Victoria and the tightening of JobKeeper more than offset a continued recovery in jobs elsewhere.

One in ten of the businesses it has contacted through its liaison program report wage cuts, most of them targeted towards senior management, but some implemented broadly.

The proportion reporting wage cuts is “significantly higher” than during the global financial crisis.

By the end of next year the bank expects the published unemployment rate to be somewhere between 11% and 7%.

The forecast range is an indication of how uncertain it is about what will happen.

The bank’s forecasts for recession and recovery have a similarly wide range.

On one hand GDP might not be back to where it was until the middle of the decade, and not back to where it would have been until the start of the following decade.

On the other, it might have made up its losses by the end of next year.

The bank’s central “baseline” forecast points to a worse recession than any since World War II and the Great Depression.

Its upside scenario assumes quick progress in controlling the virus, improving consumer confidence as a result, a quick end to the outbreak in Victoria and no further major outbreaks.

The downside scenario assumes rolling outbreaks and rolling lockdowns along with a widespread resurgence in infections worldwide.

Risks a plenty…

It says if households conclude that low income growth will be more persistent than previously expected, they might “permanently adjust their spending” leaving the economy weaker for longer.

The uncertainty could lower firms’ risk appetite, prodding them to pay down debt and increase cash buffers rather than invest even when conditions recover.

A sustained period of lower investment, combined with “scarring” as people unemployed or underemployed find themselves unable to improve their position could “damage the economy’s productive potential”.

…little harm in spending

The bank says there’s little more it can do. It has considered negative interest rates, and believes they would be of no real help.

It’ll be up to the government to support the economy with spending. Where needed the bank will buy government bonds with money it creates in order to keep borrowing costs low.

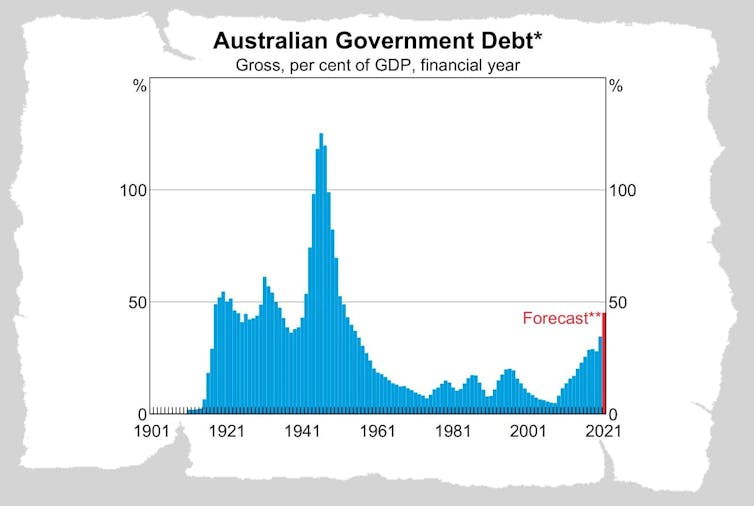

To make the point that government shouldn’t be afraid of borrowing, it includes a graph of government debt since Federation.

Its point is that as a proportion of the economy the government has borrowed and spent much much more in the past.

To the extent that it is needed to make households feel able to spend and businesses able to invest, it is worth it.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.