Sarah John, Flinders University

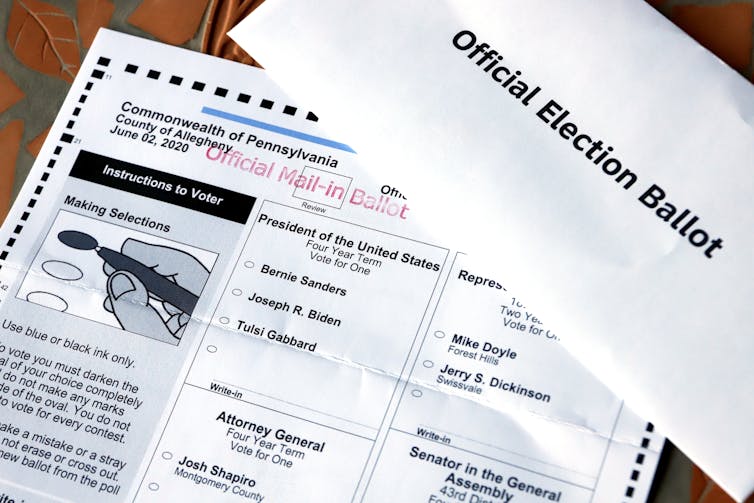

In the US election next month, record-breaking numbers of voters will cast their ballots by mail for the first time. Millions of these ballots will be processed by local election administrations inexperienced with large numbers of mail-in votes.

In this environment, many ballots are likely to be rejected for technical reasons, such as non-matching signatures (the signature on the ballot doesn’t match the signature on voter registration forms), raising the risk of protracted court battles in key battleground states.

Already, lawsuits are being filed in many of these states to try to prevent or reduce ballot rejections, which, perversely, may only make the problem worse if voters can’t keep track of constantly changing rules.

Large numbers of ballot rejections could prove pivotal if the race is close in key states like Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Michigan, which Donald Trump won by less than 80,000 votes in total in 2016 to claim victory over Hillary Clinton.

But there is also a longer-term risk to voters’ belief in the fundamentals of democracy itself if they cast a ballot that literally does not count.

How many ballots could be rejected?

According to the Election Assistance Commission (EAC), a federal agency created to help states modernise their voting systems after the “hanging chads” problem in the 2000 presidential election, less than 5% of voters in North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin voted by mail in 2016.

But 2020 will be different. In Pennsylvania, 2.5 million voters requested mail-in ballots — about eight times as many as 2016. And more than ten times as many North Carolinians requested mail-in ballots in 2020 than 2016.

A dramatic increase like this could very easily overwhelm county election administrators who are unfamiliar with the system and under-resourced to process masses of mail-in ballots.

In every election with mail-in voting, some ballots are not counted for reasons unrelated to the eligibility of the voter. Most commonly, these “rejected” ballots arrived too late, lacked the requisite signature or “secrecy” envelope or had some other technical problem.

In the 2016 presidential election, the EAC found about 1% of the 33.4 million total absentee ballots were rejected — or about 319,000 overall.

However, in some counties, rates were much higher. Nassau County, an affluent county just outside New York City, reported rejecting 82% of its mail-in ballots (mostly because they missed the deadline). Greene County, Arkansas, reported rejecting 48% of its mail-in ballots (mostly because the voter did not write their address on the envelope, which is a requirement in Arkansas).

It is likely more ballots could be rejected in this year’s election — USA Today estimates more than 1 million, if half the nation votes by mail.

We got our first taste of the problem during the Republican and Democratic presidential primaries earlier this year. More than 550,000 ballots were rejected in these contests — nearly twice as many as the 2016 general election.

Mishmash of laws and court rulings

Even in normal times, voting by mail is complex. Technical requirements and formats vary greatly from state to state.

Some states, like Pennsylvania, require the ballot to be ensconced in a second “secrecy” envelope. Without this, the ballot will be rejected.

And six states, including the key battleground states of North Carolina and Wisconsin, require a witness to verify the voter’s signature. Without this, the ballot will be rejected.

Unsurprisingly, research reveals inexperienced voters, including younger voters, are more likely to have their mail-in ballots rejected.

And while there is no evidence mail-in voting leads to widespread voter fraud — as Trump has repeatedly claimed — rejected ballots do have the potential to determine election outcomes.

For this reason, rules about accepting and rejecting mail-in ballots are currently the subject of hundreds of court actions.

In the absence of a concerted national effort to reduce ballot rejection rates, citizen and activist groups and Democratic state party organisations have filed lawsuits seeking to remove technical requirements for mail-in ballots in numerous states.

Republican state party organisations, meanwhile, are appealing those decisions and challenging policy changes that loosen technical requirements.

Using the courts in this way creates uncertainty, and may even serve to increase the number of ballots that are rejected.

In some states, court rulings that have loosened requirements have been overturned only weeks later by higher courts. In early October, for example, the US Supreme Court reinstated the witness requirement for South Carolinian mail-in voters after a lower court had ordered it removed.

Consequently, South Carolina voters have received mail-in ballots with outdated instructions, increasing the risk their votes will be rejected.

Every day, there are new court rulings. For example, last week, a Michigan appeals court overturned a lower court ruling that prevented ballots from being rejected if they arrived late, so long as they were postmarked November 2 or earlier.

This week, the US Supreme Court ruled mail-in ballots could be counted for up to three days after election day in Pennsylvania, so long as they were postmarked by November 3.

This decision could prove critical in a tight race. Trump won Pennsylvania in 2016 by just 44,000 votes out of some 6 million cast.

And in Texas, which has the most restrictive voting rules of anywhere in the country, an appeals court overturned a lower court decision this week to allow election officials to reject ballots without matching signatures without giving voters a chance to challenge.

Will ballot rejections erode trust in democracy?

There are long-term risks to these battles over mail-in voting, as well.

Voters would understandably be disheartened to learn their ballots were rejected in the election — and their votes didn’t count — after they went to the effort of voting by mail. This risks a genuine disengagement with the electoral system.

Researchers in Scotland have found high rates of ballot rejections in the 2007 Scottish parliament elections caused many to question the fairness of the electoral system, possibly resulting in lower voter turnout rates in future elections.

Not much research has emerged in the US on the effects of ballot rejection on future political participation. But this will likely change after this election, particularly if ballot rejections are widespread.

We should expect to hear many angry partisan allegations about “naked” ballots (those missing special secrecy envelopes), postmarks and signatures in the weeks after the election.

But we should also spare a thought for the citizens who find out the ballots they diligently returned were rejected on a technicality. They may not be so inclined to vote again in the future.

Sarah John, College of Business, Government and Law, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.