Justin St. P. Walsh, Chapman University and Alice Gorman, Flinders University

A new era of space stations is about to kick off. NASA has announced three commercial space station proposals for development, joining an earlier proposal by Axiom Space.

These proposals are the first attempts to create places for humans to live and work in space outside the framework of government space agencies. They’re part of what has been called “Space 4.0”, where space technology is driven by commercial opportunities. Many believe this is what it will take to get humans to Mars and beyond.

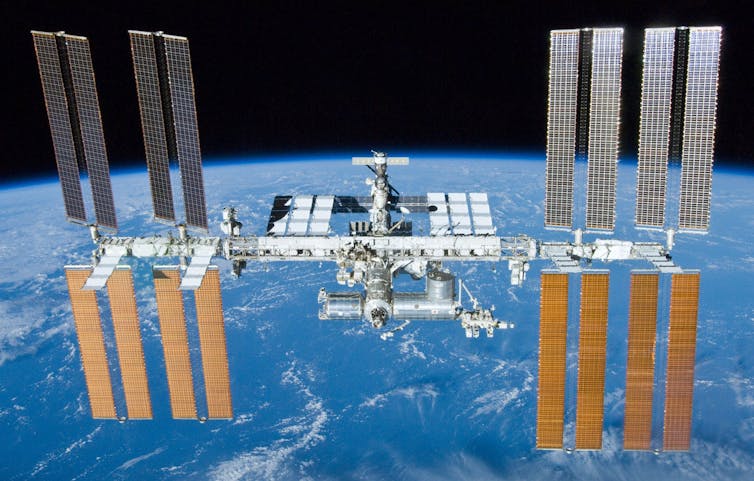

There are currently two occupied space stations in low Earth orbit (less than 2,000km above Earth’s surface), both belonging to space agencies. The International Space Station (ISS) has been occupied since November 2000 with a typical population of seven crew members. The first module of the Chinese station Tiangong was launched in April 2021, and is intermittently occupied by three crew.

The ISS, however, is slated to retire at the end of the decade, after nearly 30 years in orbit. It has been an important symbol of international cooperation following the “space race” rivalry of the Cold War, and the first truly long-term space habitat.

Plans for multiple private space stations represent a major shift in how space will be used. But will these stations change the way people live in space, or replicate the traditions of earlier space habitats?

Commercialising life in space

The change is driven by NASA’s support for commercialising space. This emphasis really started about a decade ago with the development of private cargo services to supply the ISS, like SpaceX’s Cargo Dragon, and private vehicles to deliver astronauts to orbit and the Moon, such as SpaceX’s Crew Dragon, Boeing’s Starliner, and Lockheed Martin’s Orion capsules.

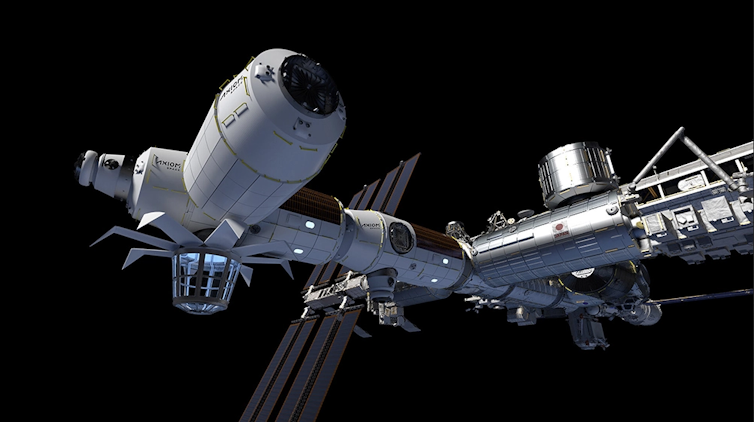

Start-up Axiom Space was awarded a $140 million contract by NASA in February 2020 for a private module to be attached to the ISS. Axiom announced Philippe Starck will design a luxurious interior.

Starck compares it to “a nest, a comfortable and friendly egg”. There’s also a huge viewing area with two-metre-high windows for tourists to look out at Earth and space.

The first module is due to be delivered to the ISS in 2024 or 2025, with others following each year. By the time the ISS is decommissioned around 2030, Axiom’s modules will become a free-flying station.

Axiom has signed a contract with French-Italian contractor Thales Alenia Space, which built close to 50% of the ISS’s habitable volume for NASA and the European Space Agency, to produce its habitat.

But there’s more. Three other groups have just been selected for the first phase of NASA’s Commercial LEO Destinations competition to build free-flying space stations to replace ISS.

First, a group composed of Nanoracks, Voyager Space, and Lockheed Martin proposed a station called Starlab to provide research, manufacturing, and tourism opportunities. This was almost immediately followed by a competing project called Orbital Reef, by Blue Origin, Sierra Space, and Boeing. A third project, by Northrop Grumman, will be made of modules based on its existing Cygnus cargo vehicle.

But how are space stations actually used?

Less clear is whether the private space stations will be more liveable than earlier generations of space stations, like Salyut, Mir, and ISS.

Typically, older space stations were designed to meet engineering constraints rather than starting with crew comfort. What lessons have been learned to make life better in space?

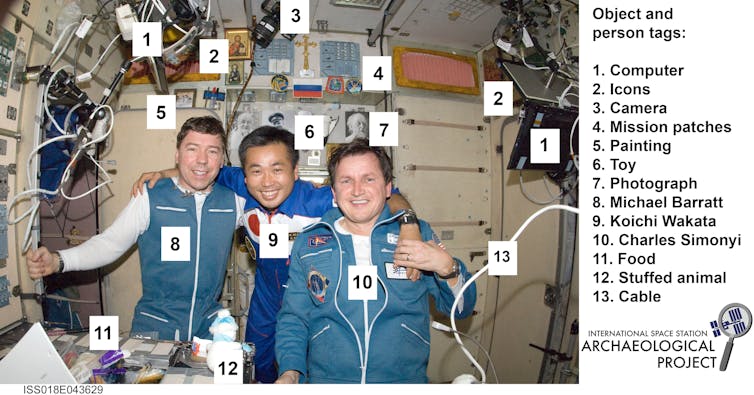

Until recently, there was little research that focused on the lived experience of astronauts on space stations. That’s where social science approaches, such as the ones we are using in the International Space Station Archaeological Project, come in.

Since 2015, we have developed new, data-driven understandings of how ISS crew adapt to life in a context of confinement, isolation, and microgravity. We observe and measure their interactions with built spaces and the objects surrounding them. What are the patterns of usage of different spaces and items?

Asking these kinds of questions reveals information never considered in habitat design before. It turns out the crew don’t necessarily use the spaces inside the ISS the way they were designed – for example, they personalise different areas with visual displays of items that reflect their beliefs, interests, and identity.

The crew also doesn’t use all spaces inside ISS equally. People from different genders, nationalities, and space agencies appear in some modules more than others among the 16 that make up the station. These patterns are related to the way work is divided up between crews and agencies, as well as the layout of the modules themselves.

One big challenge of life in orbit is the lack of gravity. Objects like handrails, Velcro, bungee cords, and resealable plastic bags act as “gravity surrogates” by fixing objects in place while everything else floats around. Our research is mapping how crew adapt these gravity surrogates to make their activities more efficient, and how the placement of the surrogates changes the way different spaces are used.

Society and culture in space

Even with added luxury features like large windows, designers and engineers have a long way to go to make space stations efficient, comfortable, and welcoming, especially for the predicted space tourism market.

The plans for privately-owned and -operated space stations are undeniably ambitious and could transform how humans live in this environment. But it’s likely that the companies working on them don’t yet know what they don’t know about how people actually use space habitats.

Only by turning towards new kinds of questions and research from a social and cultural perspective will they be able to make real changes that can improve mission success and crew well-being.

Justin St. P. Walsh, Associate professor of art history and archaeology, Chapman University and Alice Gorman, Associate Professor in Archaeology and Space Studies, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.