Joanna Allan, Northumbria University, Newcastle

Morocco has positioned itself as a global leader in the fight against climate change, with one of the highest-rated national action plans. But though the north African country intends to generate half its electricity from renewables by 2030, its plans show that much of this energy will come from wind and solar farms in occupied land in neighbouring Western Sahara. Indeed, in my research I have looked at how Morocco has exploited renewable energy developments to entrench the occupation.

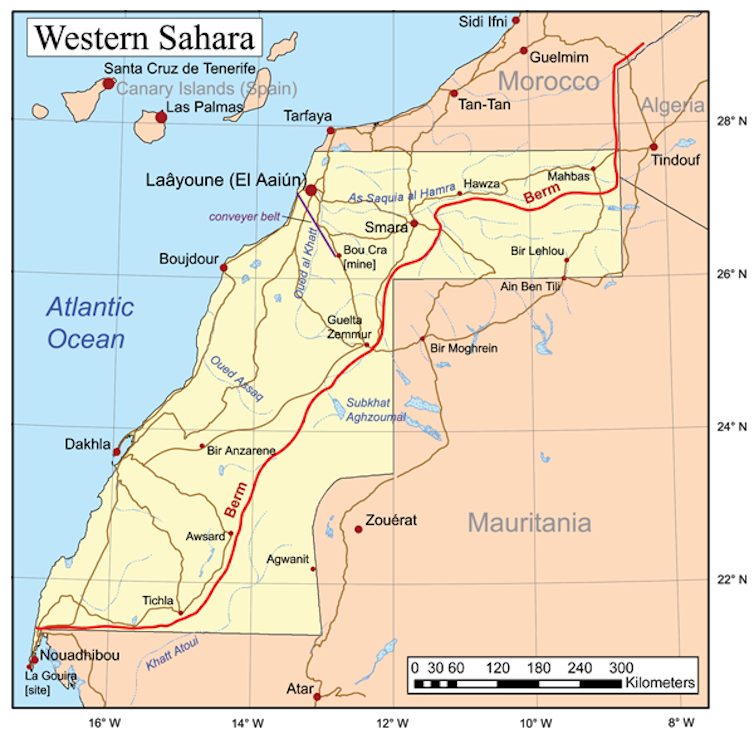

Western Sahara, a sparsely-populated desert territory bordering the Atlantic Ocean, is Africa’s last colony. In 1975, its coloniser Spain sold it to Morocco and Mauritania in exchange for continued access to Western Sahara’s rich fisheries and a share of the profits from a lucrative phosphates mine.

According to Morocco, Western Sahara formed part of the Moroccan sultanate before Spanish colonisation in the 1880s. However, that year the International Court of Justice disagreed, and urged a self-determination referendum on independence for the indigenous Saharawis. Nevertheless, Morocco invaded and used napalm against fleeing Saharawi refugees.

Tens of thousands of Saharawis fled to neighbouring Algeria, where the Saharawi liberation front, the Polisario, established a state-in-exile, the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). Other Saharawis remained under Moroccan occupation.

Today a sandy wall, or berm, runs the length of the country and everything to the east of the berm remains under the control of the Polisario. Numerous landmines deter a large-scale return of refugees, though some Saharawi nomads do live there.

Morocco and Polisario were at war until 1991, when the UN brokered a ceasefire on the promise of a referendum on independence for Saharawis. This referendum has been continuously blocked by Morocco, which considers Western Sahara part of its “southern provinces”.

Since the 1940s the UN and its special committee on decolonisation has maintained a list of non-self governing territories. As territories gained independence, they have gradually been ticked off the list, and those that remain are almost all small Pacific or Caribbean island nations.

In each case, an “administering power” (usually the UK) is officially noted. Western Sahara is the only African territory remaining on the list. It’s also the only territory where the administering power column is left blank – a footnote explains the UN considers it a “question of decolonisation which remained to be completed by the people of Western Sahara”. Morocco however doesn’t see itself as the occupying power or even as the administering power but says that Western Sahara is simply part of its country.

In November 2020, armed war resumed between the two parties. In a recent journal article, my colleagues Mahmoud Lemaadel, Hamza Lakhal and I argue that the exploitation of natural resources, including renewable energy, played no small role in provoking this renewed war.

Renewable energy from occupied land

Western Sahara is very sunny and surprisingly windy – a natural renewable energy powerhouse. Morocco has exploited these resources by building three large wind farms (five more are planned) and two solar farms (another is planned).

But these developments have made Morocco partly dependent on Western Sahara for its energy supply. Morocco already gets 18% of its installed wind capacity and 15% of its solar from the occupied territory, and by 2030 that could increase to almost half of its wind and up to a third of its solar. That’s according to a new report Greenwashing the Occupation by Western Sahara Resource Watch, a Brussels-based organisation I am affiliated with.

In its nationally determined contribution (NDC) to the Paris climate agreement, Morocco reports on developments in occupied Western Sahara – which it calls its provinces sud (southern provinces) – as if they were in Morocco. This energy dependence entrenches the occupation and undermines the UN peace process.

According to Saharawi researchers, several Saharawi families have been forcibly evicted from their homes to make way for some of these solar farms. My colleagues have also documented forced eviction associated with the development of the wider energy system in Western Sahara.

Saharawi refugees have used solar panels for domestic energy since the late 1980s. The SADR-in-exile would now like to roll out small-scale wind and solar installations in the part of Western Sahara that it controls, in order to power the communal wells, pharmacies and other services there that are used by nomads.

I was recently part of a team that assisted the SADR in developing an indicative nationally determined contribution (iNDC) – essentially an unofficial version of the climate action plans each country was required to submit ahead of the recent UN COP26 climate summit in Glasgow.

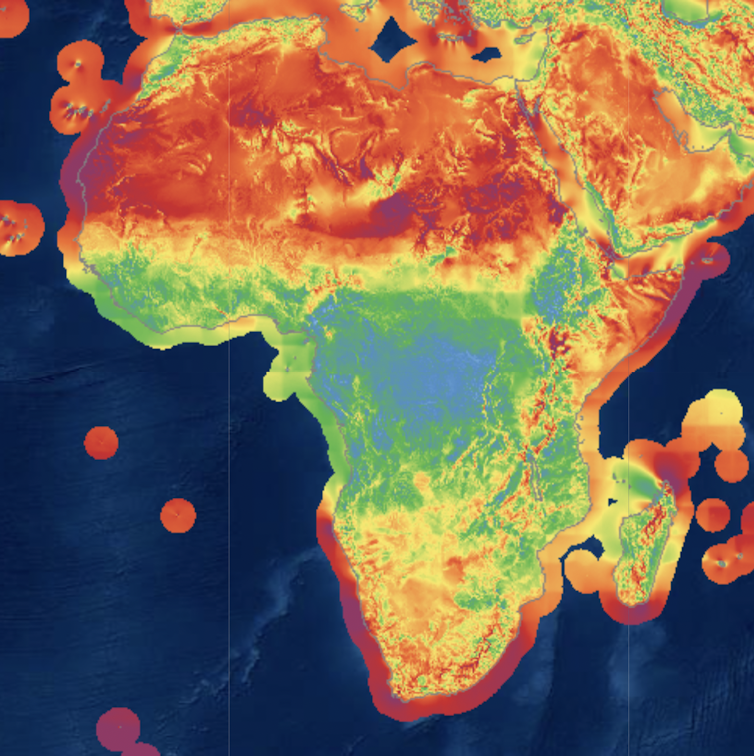

SADR hopes this may help to attract climate finance. The iNDC can also be interpreted as a challenge to climate injustice. While having negligible responsibility for the climate emergency, the Saharawis nevertheless face some of its worst impacts: ongoing sand storms, flash flooding, and summer temperatures of over 50°C.

The formal NDC process excludes occupied and displaced populations such as Saharawis from global conversations on how to tackle the climate emergency. The iNDC is an assertive step to demand that Saharawis are heard.

Joanna Allan, Senior Lecturer, Northumbria University, Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.