William McDougall, Glasgow Caledonian University

The Scottish elections on May 6 are potentially shaping up to have a big impact on the constitutional future of Scotland and the UK. There is little doubt about who the largest party will be after the elections. Despite 14 years in power, the Scottish National Party (SNP) will get there comfortably.

First of all, there are the high ratings of the first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, for her handling of the coronavirus. These compare favourably not just to her rivals in Scotland but also to the ratings of UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

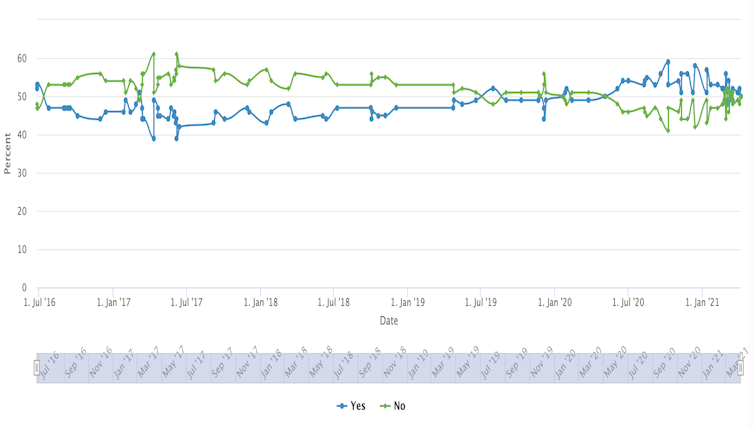

However, the SNP will remain dominant for other reasons too. There is the impact of two referendums. The first on independence, which divided Scotland on its constitutional future in the UK in 2014. The second on the UK’s membership of the EU in 2016, which led to Brexit but was rejected by the majority of voters in Scotland. Five years on, most recent polls are showing a pro-independence majority in Scotland.

Scottish independence poll tracker

The nature of Scotland’s electoral system, ironically created by a Labour government, also benefits the SNP. The parliament has 129 members and voters have two votes – the first for a candidate and the second for a party. The first vote is for the 73 constituency MSPs (Members of the Scottish Parliament) and the other is for the 56 regional list MSPs, in which the party votes are used to make the overall result more proportional to voting behaviour.

The SNP will dominate the constituency seats as they will win the support of most independence supporters, while the pro-union parties will split the unionist vote among themselves. Because there are more constituency seats than list seats, this means that the SNP tends to come out top overall.

Any other business?

Although the SNP will almost certainly remain dominant in Scotland, there are numerous other questions that still need to be answered. First, who will finish second? Either the Conservatives or Labour. Both have new leaders in Scotland since the last election there. In 2016, the SNP won 63 seats (down six from 2011), two short of an outright majority. The Conservatives won 31 (+16), Labour won 24 (-13) and the Greens and Lib Dems won 6 (+4) and 5 (-) respectively.

The Conservatives’ Douglas Ross supports the idea of a unionist alliance. He reportedly tried and failed to persuade Labour’s Anas Sarwar and the Lib Dems’ Willie Rennie to agree to a public pledge to refuse to work with any pro-referendum parties and to come together to force out the SNP if there were sufficient numbers in Holyrood. Ross will now be focused on portraying his party as the main unionist opposition to Sturgeon’s SNP.

Labour will mostly likely try to play to what they view as their strength: not talking about the constitution and focusing on other issues. This appeals to certain voters but they could just as easily end up squeezed unless Sarwar can break through. That’s a tough task in a rather polarised electorate. Focusing on the post-COVID recovery may aid Labour, or it could just remind voters that Sturgeon is considered to have performed well during the pandemic.

Finishing second is really the dream for Labour. Having lost votes at every previous Scottish parliamentary election, it would certainly be an improvement, albeit they would still be distantly behind the SNP. The party that was once the dominant force in Scotland remains a shadow of its former self.

The joker in the pack is the former first minister, Alex Salmond, the leader of the new Alba party. Twice SNP leader and with over 30 years in front-line politics, he is a formidable campaigner. Yet Salmond’s popularity is much diminished, with ratings below those of Boris Johnson.

Nonetheless Salmond is a renowned gambler. He is hoping his new Alba party can persuade enough SNP voters to back his party on the regional list. Alba has attracted those independence campaigners unhappy with Sturgeon’s more cautious leadership of the SNP, though Salmond has become a controversial figure following the parliamentary inquiry into the handling of his sexual assault charges.

Salmond has talked about achieving a “supermajority” for independence at the May election, though so far the opinion polls have been variable: some say Alba will win a few seats and that the pro-independence parties will achieve a supermajority, while others predict that Salmond could deprive the SNP of a majority without Alba winning any seats.

This may also affect the pro-independence Scottish Greens. They could end up with a similar role to 2016-21, providing crucial votes to the SNP government in return for some of their policies being adopted – or in coalition.

Trouble for Johnson

From the UK government’s perspective, ideally the SNP will fall short of winning a majority of seats. This would make it easier for Johnson to refuse to allow Sturgeon to hold another independence referendum.

However, if the SNP does well and the pro-independence parties do win a large majority, forces outside the SNP may become more important. The more hardline yes supporters no doubt hope that Alba could win enough regional list members to allow up to two-thirds of seats to be controlled by the pro-independence parties.

If blocked from holding a referendum by Westminster, a two-thirds majority would give the pro-independence forces control over the Scottish parliament’s ability to dissolve itself. This would allow a fresh election to be potentially held as a direct plebiscite on independence, setting Scotland on a collision course with Westminster.

This is unlikely, however. Alba may not win the number of seats they dream of and Sturgeon’s more moderate approach is extremely unlikely to sanction such a move, wary of the recent example of Catalonia, where a unilateral declaration of independence failed.

Nevertheless the SNP, facing competition for the first time from another party whose primary purpose is also independence, may still feel pressured to push for a referendum through the Scottish parliament with or without the support of Westminster. But Sturgeon would only proceed with such a strategy if the referendum were legal, and opinion on that remains disputed.

In short, it’s a vital election in Scotland. As the UK slowly emerges from the pandemic, a constitutional clash between supporters of Scottish independence and Johnson’s UK government looks a distinct possibility. The situation is only likely to get more intense as we move towards May 6.

William McDougall, Lecturer in Politics, Glasgow Caledonian University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.