Fraser McMillan, University of Glasgow; Ailsa Henderson, University of Edinburgh, and Jac Larner, Cardiff University

The previous Scottish parliament election, in 2016, came less than two years after the country’s historic referendum on independence from the rest of the United Kingdom. That contest – a Pyrrhic victory for the pro-union side – reshaped Scottish politics. The party system consolidated around voters’ constitutional preferences, and the ruling Scottish National Party’s hold on pro-independence voters led it to a strong victory in 2016, even as it lost some of its 2011 supporters.

A quick look at opinion polls would suggest that little has changed: the SNP are again set to win big. But there’s a lot more to the story. The last five years have been full of twists and turns, overlaying the existing constitutional divide with another. The Brexit referendum took place shortly after the Holyrood vote and – two prime ministers and two general elections later – the UK eventually left the EU in early 2020.

Adding to this, new leaders and new parties are feeding into the totemic constitutional debate, which now spans two unions. This has split the Yes/No binary in Scotland into four distinct tribes – and these can help us understand what’s going on under the surface.

Scotland’s four tribes

Scotland’s four tribes correspond to the four constitutional boxes that voters can be placed into according to their attitudes on Scottish independence and EU membership. The first is No/Remain – those people who voted against independence and against leaving the EU. The second is No/Leave – those who voted against independence but for leaving the EU.

The Yes/Remain group is made up of people who voted in favour of independence but against leaving the EU, while the Yes/Leave group is made up of people who voted in favour of both independence and leaving the EU.

Political scientists have shown that, in Britain as a whole, the Leave/Remain divide drives political and social polarisation. hese identity-based groupings became lightning rods for people’s values, beliefs and attitudes on all sorts of topics – from the death penalty to brown sauce. This defining cultural divide maps more cleanly onto Leave vs Remain than Conservative vs Labour, at least for now.

In Scotland, however, the independence question predated the cleavage on EU membership. It shaped how Scots responded to the question of Brexit and helps explain why they voted decisively in favour of Remain even as England and Wales broke for Leave. When it comes to polarisation, the existence of four identity groupings makes things more complicated. Constitutional preferences cut across demographics and other political attitudes, and the tribes are not symmetrical.

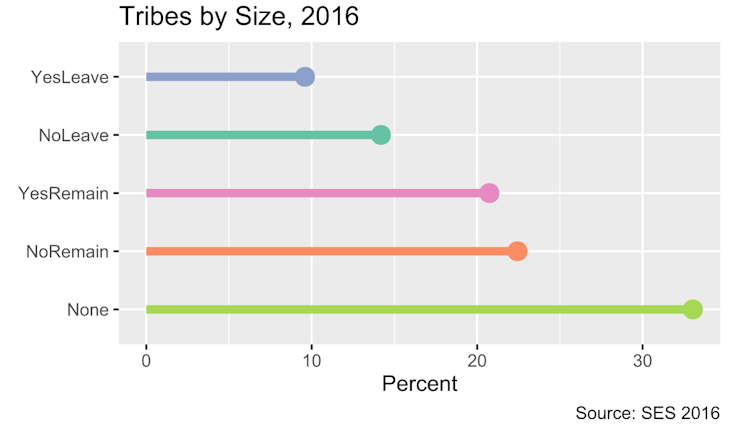

This graph, based on Scottish Election Study data, shows the share of each group in the electorate in 2016 alongside respondents who didn’t express a preference on at least one constitutional axis.

The No/Remain group, nominally the “winners” of both referendums in Scotland, was the biggest tribe at that point in time. However, recent growth in support for independence is largely down to voters in this group switching camps. EU membership was one of the central planks of the anti-independence Better Together campaign in 2014, and this has now been fatally undermined. Current opinion polling suggests that Yes-supporting Remainers now outnumber those who would reject independence. As we shall see, this likely plays into the SNP’s hands for the 2021 vote.

Tribal competition

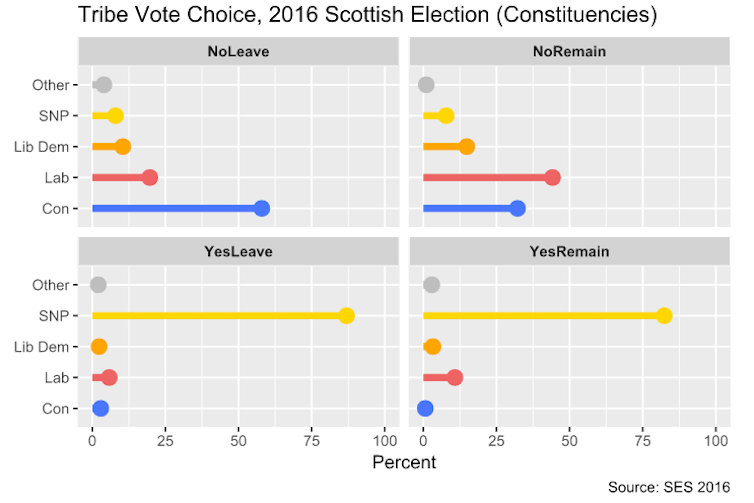

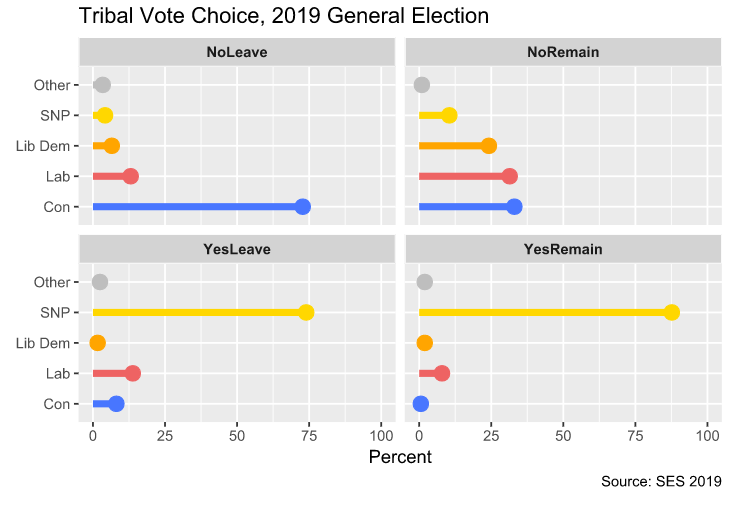

The next two graphs show how each tribe voted in the 2016 Holyrood constituencies and in the 2019 Westminster general election. As one might expect, the SNP dominates among those who back both independence and Remain.

The same is true of the Conservatives and No/Leavers – but the pull is not equal. The pro-independence camp delivers more voters to the SNP than Brexit does to the Conservatives, and this remained true even after the Conservatives became the bastions of Brexit in the wake of the 2016 referendum.

These graphs also show that Yes/Leavers behave more like Yes voters than Leave voters, suggesting that independence trumps Brexit support for those who favour two types of constitutional change. However, this relatively small group is also the only one without an obvious party tribune.

There may be scope for a pro-independence, anti-EU party to compete with the SNP for this group in future. This is something former first minister Alex Salmond’s new regional list-only electoral vehicle Alba has flirted with. However, his personal unpopularity may be hard to overcome.

In contrast with the underserved Yes/Leavers, the No/Remainers are spoiled for choice. However, Labour and the Liberal Democrats, the two parties whose platforms match these voters’ constitutional preferences, do not perform particularly well. Why might this be the case?

Identity intensity

Scratching under the surface, members of each tribe vary in terms of the intensity of their preferences on independence. Strong supporters of independence back the SNP, and strong opponents back the Conservatives. But if we distinguish between strongly and weakly committed supporters of each side, we find that Conservative support drops among moderate opponents of independence. Meanwhile, SNP support remains strong for moderate supporters of independence (60%), people who are neutral (38%) and even moderates on the other side of the fence (20%).

In other words, the tribes all contain voters who care more or less about independence (and the same is true of Brexit) – and this exerts its own influence on vote choice. One reason for enduring SNP success is that the party dominates its own natural constituency and makes inroads into Leave and even No supporters.

Other parties, like Scottish Labour, are not only fishing in a smaller pool, but have a hard time winning over the voter groups who align most closely with them. This pattern doesn’t look like it will change: Labour’s new leader Anas Sarwar is much more popular than the Scottish Conservatives’ Douglas Ross – but in terms of party support, the Conservatives still look likely to beat them again.

Fraser McMillan, Research Associate (Politics), University of Glasgow; Ailsa Henderson, Head of Politics and International Relations, University of Edinburgh, and Jac Larner, Lecturer, Politics, Cardiff University, Cardiff University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Explore top-rated compensation lawyers in Brisbane! Offering expert legal help for your claim. Your victory is our priority!

Explore top-rated compensation lawyers in Brisbane! Offering expert legal help for your claim. Your victory is our priority!

"

"